Article

The Key to Kicking Your Sugar Habit Is in Your Brain- Not Your Tastebuds

Sugar substitutes sure taste sweet, but let’s be honest, they’re never quite as satisfying as the real thing. And until now, science has never been able to explain why. But recently, researchers at Columbia University’s Zuckerman Institute have discovered neurons in the brains of mice that respond to sugar – not only on the tongue, but also in the gut.

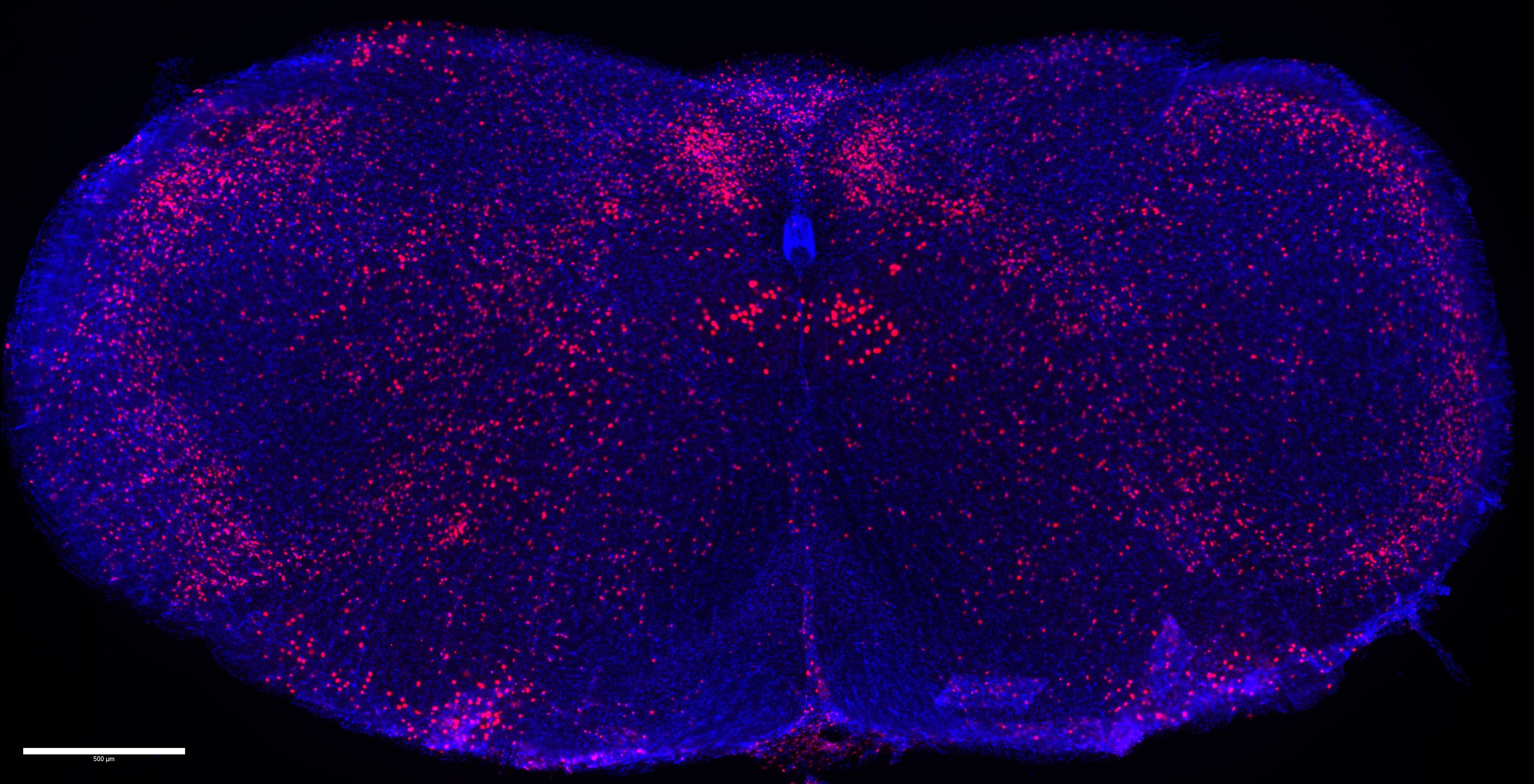

Sugar-sensing neurons (pink) in cNST brain region of a mouse. Photo Credit: Hwei-Ee Tan:Zuker lab:Columbia's Zuckerman Institute

Sugar substitutes sure taste sweet, but let’s be honest, they’re never quite as satisfying as the real thing. And until now, science has never been able to explain why. But recently, researchers at Columbia University’s Zuckerman Institute have discovered neurons in the brains of mice that respond to sugar – not only on the tongue, but also in the gut. And it provides a plausible theory about why artificial sweeteners just don’t seem to quench our sugar cravings the way we wish they would: they merely trick the tongue – but receptors in the gut tell the brain something different.

The study, "The gut-brain axis mediates sugar preference, " was published last week in the journal Nature.

"When we drink diet soda, or use sweetener in coffee, it may taste similar, but our brains can tell the difference," said co-author Hwei-Ee Tan. "The discovery of this specialized gut-brain circuit that responds to sugar -- and sugar alone -- could pave the way for sweeteners that don't just trick our tongue but also our brain."

Artificial sweeteners, such as NutraSweet and Stevia, work by activating the same signal pathways from the tongue to the brain. They switch on sweet taste receptors to fool the brain into thinking that sugar has landed on the tongue. But when researchers deleted those sweet taste receptors, the animals not only still demonstrated a preference for sugar, but a specific area of the brain called the caudal nucleus of the solitary tract, or cNST lit up.

"Something was transmitting a signal, indicating the presence of sugar, from the gut to the brain," said Alexander Sisti, PhD, the paper's co-first author.

The research team also recorded activity in the vagus nerve- a nerve that connects the brain to various organs of the body, and found these cells reacted to sugar as well, indicating a direct sugar sensing pathway from the gut to the brain. Further experiments uncovered a specific sugar-transporting protein in the gut called SGLT-1, that is a key sensor transmitting the presence of sugar from the gut to the brain via what is known as the gut-brain axis.

The team also demonstrated that shutting down this gut-brain circuit completely abolishes the animals' craving and preference for sugar. By contrast, activating these cells every time the animal consumed a sugar-free drink, caused them to behave as if they were getting the real thing.

Researchers hope that by providing a basis for understanding the way the brain responds to sugar, they may eventually find novel therapeutic ways to modify its response, curb our taste for it, or find substitutes which more closely mimic the effects sugar has on the brain.

Since excess sugar consumption is linked to obesity and diabetes, these findings could have important public health implications.