Article

Polyarteritis Nodosa Presenting As Calf Pain

Author(s):

This young woman presented with severe leg pain, night sweats, and fever of unknown origin. The diagnosis of polyarteritis nodosa had several unusual features.

An 18-year-old Hispanic female with no significant medical history presented to our hospital with severe, debilitating pain and weakness in both calves, intermittent fevers over the past three months, drenching night sweats, and new-onset upper extremity bilateral weakness and pain during the previous three weeks. Her fevers, which had increased from once weekly to twice daily over the past month, usually arrived in the afternoon, with associated chills, frontal headache, nausea, photophobia, phonophobia, and dizziness. She also reported decreased appetite and a 5 kg weight loss over the prior six months.

The calf pain and weakness had begun four months earlier, concurrent with an upper respiratory infection that resolved within two weeks. This episode was not associated with cough, fever, chills, or night sweats. She had no prior history of respiratory problems.

She was born in Mexico, has lived in California with her parents and four siblings since the age of 5, and said she has not travelled since. Nor has she gone camping in forest areas or swimming in lakes, although she visited some farm animals five months earlier at a country fair. She takes care of a dog and a turtle at home, and likes to eat queso fresco made from unpasteurized milk. She denied use of alcohol, tobacco, or illicit drugs, and any sexual activity. There is no noteworthy family medical history.

By the time she reached our hospital, the patient appeared thin, pale, frail, and younger than her stated age, but in no distress. Physical examination revealed a temperature of 100°F, blood pressure of 114/57 mmHg, pulse of 112 bpm, respiratory rate of 14/min, oxygen saturation of 100% on room air, and a BMI of 17 (below 3rd percentile for her age). She had no skin rashes, and lymph node, heart, lung, abdominal, and neuromuscular exams were all unremarkable.

Her upper extremity strength was normal (5/5, although limited by some pain) with full active and passive range of motion. She had some mild, asymmetric, patchy areas of tenderness in the shoulders, upper arms, and elbows, but no swelling, synovitis, or bony tenderness. Her lower extremity strength was limited to about 4/5 because of exquisite pain, particularly when squeezing her calves lightly. She could plantar flex and dorsiflex actively in bed, but she refused to stand or walk due to pain. Her sensory exam revealed no gross deficits or hyperesthesia.

Click here to continue to the Assessment, Discussion, and Outcome

Assessment

A month before we saw the patient, her pediatrician recorded the following laboratory results: C-reactive protein (CRP): 7.7 mg/dL; erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR): 67 mm/h; hemoglobin: 7.1 g/dL, but no leukocytosis. She was admitted twice to a children’s hospital during the following month, where she had an extensive workup, including consultations with specialists in pediatric rheumatology, hematology, gastroenterology, and infectious diseases. Test results revealed microcytic anemia from iron deficiency, elevated ESR (80 mm/h) and CRP (15.5 mg/dL), and leukocytosis (15,000 leukocytes with 83% neutrophils).

Numerous other serum chemistry tests, liver enzymes, and urinalysis were normal, as were blood and stool cultures and the results of an exhaustive workup for infection (HIV, hepatitis B or C, cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, West Nile virus, parvovirus B19, ricketssia, coccidiodes, streptococcus, tuberculosis, Bartonella, tularemia, Brucella, and Coxiella).

Her anti-nuclear antibody (ANA) was positive at a low 1:40 titer, but with negative ANA subsets and normal complement levels. She had a negative anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) and rheumatoid factor, a negative workup for celiac disease, normal levels for IgA, IgG, and IgM, triglycerides, and soluble IL-2 receptor, a normal D-dimer, and a slightly elevated fibrinogen level (572 mg/dL). Results of a lumbar puncture were unremarkable. Two bone marrow biopsies revealed trilineage hematopoeisis, absent iron stores, no blasts, negative stains for acid-fast bacilli and fungi, and a normal female karyotype.

Brain MRI, lower extremity Doppler ultrasound, echocardiogram, abdominal ultrasound, and CT of the chest were all normal. However, calcified mediastinal lymph nodes were suggestive of prior granulomatous exposure, which was confirmed on a PET/CT scan.

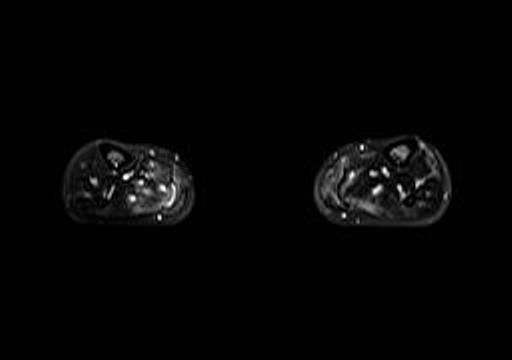

Fig. 1a. Coronal T2 gadolinium-enhanced fat

saturation MRI.

A lower extremity MRI (Figure 1a, left) revealed myositis of the calves, although creatine kinase, LDH, and aldolase levels were normal. It showed diffuse, relatively symmetric edema and increased T2 signal and enhancement within the bilateral vastus lateralis, medial and lateral heads of the gastrocnemius, and portions of the soleus, all suggestive of myositis. There was no abscess. Symmetric minimally prominent inguinal lymph nodes were seen bilaterally, and the bone marrow pattern was compatible with reactive hyperplasia.

Fig 1b. Axial T2 fat saturation MRI (calves).

After the second stay at the children’s hospital, she was discharged with naproxen and iron sulfate and the diagnoses of iron deficiency anemia and fever of unknown origin (FUO), likely from myositis of the lower extremities of unknown etiology. A myositis panel returned negative for auto-antibodies to PL-7, PL-12, Mi-2, Ku, EJ, OJ, SRP, and Jo-1.

After discharge, the patient continued to have intermittent fevers (up to 105°F) once or twice a day, and progressively worsening bilateral weakness in the calves and shoulders with intermittent, sharp pain brought on by movement and weight-bearing. Neither NSAIDs nor narcotics provided much relief for the pain, which prevented her from walking without assistance.

Her initial lab results at our hospital showed leukocytosis with left shift, unchanged anemia, continued elevated inflammatory markers, and negative pregnancy tests and urine toxicology. At this time she denied any continued headaches or dizziness, rectal bleeding, or worsening periods.

We suspected an inflammatory myositis affecting the distal lower extremities and possibly starting to affect the proximal upper extremities, so we ordered a surgical biopsy on the left calf muscle.

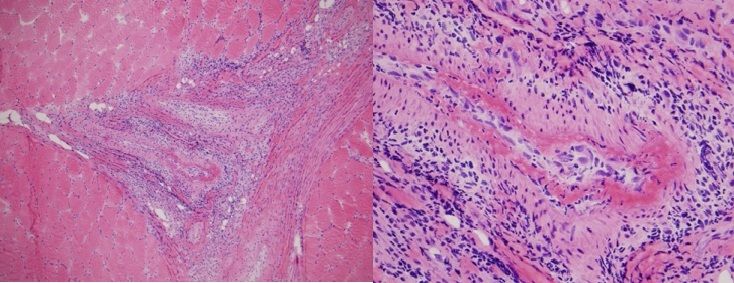

Diagnosis: Polyarteritis nodosa

Muscle biopsy (Figure 2, below) revealed significant central nucleization and two foci of arteritis and periarteritis with fibrinoid necrosis of medium-sized arteries in the setting of normal muscle tissue, which was consistent with polyarteritis nodosa (PAN). No atrophy, hypertrophy, target fibers, interstitial fibrosis, fiber necrosis, fiber regeneration, or fiber vacuolization were visible in the surrounding muscle tissue. The higher power view demonstrates fibrinoid necrosis in the arterial wall surrounding the vascular lumen. A mixed inflammatory infiltrate composed of neutrophils, lymphocytes, plasma cells and histiocytes was identified in the vessel wall and in the perivascular tissue.

Fig. 2. Left calf muscle biopsy demonstrating polyarteritis nodosa.

Hematoxylin and eosin stain. 100x (left) 400x (right)

Rheumatology consultation recommended completing the infectious and neoplastic workup, with a repeat hepatitis panel and a CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis with contrast, to evaluate for organ involvement and malignancy. As these tests returned negative, the overall clinical picture appeared consistent with myositis due to idiopathic primary PAN, limited to her lower extremity muscles and possibly her shoulder muscles.

This link will take you to the Discussion

Discussion

Classically, PAN is secondary to hepatitis B virus infection within the previous 6 months and often arises prior to active hepatitis. However, it can occur secondary to other infections (HIV, hepatitis C, parvovirus B19, certain bacteria), inflammatory conditions (rheumatoid arthritis, Sjogren’s disease), or malignancy (especially leukemia or lymphoma). It can also occur in isolation.1

PAN is defined as a non-granulomatous, necrotizing arteritis of medium or small muscular arteries that can be systemic, but without glomerulonephritis or vasculitis in the arterioles, capillaries, or venules, and not associated with ANCAs [6]. The population prevalence of PAN has been estimated as ranging from 9-77/million and the annual incidence is estimated to be anywhere from 1- 5/million/year. These numbers vary widely by region, differences in diagnostic criteria, and the prevalence of hepatitis B, which although more common in Asia and Alaska has decreased significantly over time.1. 24- 25

As with any FUO , the differential diagnosis is very broad; hence the large work-up for infectious, inflammatory/ischemic, and malignant conditions. In this case, the differential diagnoses for infectious causes included osteomyelitis, infectious myositis or vasculitis, coccidiomycosis, endocarditis, HIV, and tuberculosis (to name a few). Possible inflammatory/ischemic causes included an idiopathic inflammatory myositis, thromboemboli, periodic fever syndromes, systemic lupus erythematosus, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, antiphospholipid syndrome, and systemic vasculitides such as PAN, Takayasu’s arteritis, Churg-Strauss syndrome, Henoch- Schonlein purpura, and cryoglobulinemia. Malignant causes included leukemia, lymphoma, other lymphoproliferative disorders, macrophage activation syndrome, and primary bone tumors.

In PAN restricted to the lower extremities, markers of inflammation such as ESR and CRP are elevated, and creatinine kinase and aldolase levels are within normal limits. Electromyography is often normal. MRI showing hyperintense T2-weighted signals and gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted signals in and around muscles are highly diagnostic of inflammation. However, as these patients otherwise do not usually fulfill the 1990 ACR classification criteria for PAN (sensitivity 82%, specificity 87%), the diagnosis should be confirmed by a high-yield biopsy of a localized area of inflammation seen on MRI.

Histology typically shows segmental, necrotizing, non-granulomatous transmural inflammation of medium-sized and small muscular arteries. The focal necrotizing inflammatory lesions appear to be of different ages, with a mixed cellular infiltrate of mostly polymorphonuclear leukocytes and mononuclear cells; sometimes leukocytoclasis is seen. Inflammation can cause intimal proliferation through the wall of small and medium vessel arteries leading to fibrinoid necrosis and vessel wall disruption, which may lead to aneurysmal dilatation. Healed arteritis can cause vessel occlusion from prior proliferation, and thrombosis may also occur.1-6

Upon review of the literature, we found fewer than 30 reports of vasculitis limited to the lower extremity muscles, and in small case series at least 40% had biopsies consistent with PAN.2-5,7- 23 Leukocytoclastic vasculitis was seen in the remaining cases . (Responses to treatment and outcomes for both are similar.) 3 Muscular PAN presenting as a FUO is even more uncommon.2

In classic PAN, involvement of the renal and visceral arteries is characteristic, along with constitutional symptoms, peripheral neuropathy and joint involvement. A subset of patients can present with localized or limited disease that usually has a more benign course, most commonly in areas like the skin but also in the appendix, gallbladder, pancreas, uterus, testes, peripheral nervous system, kidneys, gastrointestinal tract, or muscle (as in our case).1-3

Fever, malaise, and significant weight loss (2-9 kg) occur in 50-80% of PAN cases, as in our patient. In muscular PAN, the calf is the most frequently affected site, followed by the thigh. About 60-80% of cases are bilateral. The pain can be from ischemic claudication (about 10%) or myalgias (50-60%), but it is rare to have myopathy. PAN restricted to the lower extremities more commonly affects middle-aged individuals, and affects both sexes equally, unlike systemic PAN, which peaks in the 6th decade with a male-to- female ratio of 1.5:1. Most patients have a long history of intermittent symptoms ranging between 3 weeks to 7 years, with a median time to diagnosis of about 14 months.1-5,24- 25

The PAN in our patient was atypical because of her young age and its rapid presentation limited to the lower extremities, leading to diagnosis within 5 months. Although muscular involvement as the sole manifestation in a vasculitis of the lower limb is rare, cutaneous involvement (livedo reticularis, tender subcutaneous nodules, purpura, ulcers, and other vasculitis lesions) occurs in about 40-50%, and even more frequently in PAN.1-5 This later happened in our case, as described below.

Systemic PAN can be rapidly progressive and fatal if untreated. But after remission has been achieved, relapse and recurrence tend not to occur. Relapse is seen more often in limited PAN; however, limited forms tend to have a more benign course than systemic PAN A clinical response to corticosteroids in limited PAN is typically achieved within one week, but the relapse rate is highly variable (from 50-90% at 3-34 months in small case series). This often depends on the time course of tapering the corticosteroids.1-5

Sometimes colchicine or immunosuppressive medications like azathioprine, methotrexate, or cyclophosphamide are used for recurrent cases and/or as a steroid-sparing agent, and rarely intravenous immunoglobulin and plasma exchange have been used for resistant cases. There has also been a report of successfully treating PAN limited to the calf muscles, fascia, and overlying skin using ultrasound-guided steroid injections into the involved muscles, along with oral azathioprine.4

The risk of progression from limited to systemic PAN is extremely low, but all these patients require close long-term follow-up.2-5,7- 9 MRI correlates well with clinical evolution and can be used serially to visualize response to treatment, as well as to assess for recurrence.

Outcome

Because diagnostic testing suggested limited PAN, the patient was treated initially with corticosteroids alone (intravenous methylprednisolone 750 mg daily for three days). Within 24 hours of the first dose she noted marked improved in pain and resumed walking without assistance. Fevers and shoulder pain disappeared, and her appetite improved. After her third dose, we reduced her daily prednisone dose to 30 mg, and she did well.

A month later, tests revealed a normal ESR and CRP and resolved anemia. But she had gained weight, was developing moon facies, and had difficulty sleeping, so prednisone was tapered, and she was started on oral methotrexate as a steroid-sparing agent along with folic acid. We referred her to physical therapy for lower extremity strengthening, and she was counseled about contraception while on methotrexate. Four months later she was symptom-free and able to run again, with a normal CRP, on methotrexate 20 mg orally weekly, folic acid 1mg daily, and prednisone 7.5 mg daily.

However, a month later she began experiencing significant nausea and without informing us she discontinued methotrexate, remaining on prednisone only. Two months afterwards, she experienced a relapse of fevers and calf pain with an elevated CRP, and we increased her prednisone to 20 mg daily. The fevers and calf pain resolved.

A few weeks later, erythematous, tender subcutaneous nodules developed on both her lower extremities. She was immediately sent to dermatology for a biopsy, which revealed necrotizing vasculitis within the walls of medium-sized arteries in the deep dermis, consistent with PAN. Stains for infections were negative.

After seeing the biopsy results, we increased her prednisone to 40 mg a day. The nodules resolved within a month. She was then started on weekly injections of 25 mg methotrexate, which did not cause nausea, and her prednisone was eventually tapered down to 5 mg/d over four months. About a year after her initial diagnosis, she continues to be doing well with no further relapses.

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr. Sheryl Boon, Dr. George Lawry, and Dr. Ronald Kim for their clinical contributions throughout this case.

References:

REFERENCES

1. Watts R, Scott DGI. Polyarteritis nodosa and microscopic polyangiitis. In Rheumatology, 5th edn. Edited by: Hochberg MC, Silman AJ, Smolen JS, Weinblatt ME, Weisman MH. Mosby Elselvier, Philadelphia. (2011) 1523-1534.

2. Kamimura T, Hatakeyama M, Torigoe K, et al. Muscular polyarteritis nodosa as a cause of fever of undetermined origin: a case report and review of the literature.Rheumatol Int (2005) 25:394-397.

3. Khellaf M, Hamidou M, Pagnoux C, et al. Vasculitis restricted to the lower limbs: a clinical and histopathological study.Ann Rheum Dis (2007) 66: 554-556.

4. Ahmed S, Kitchen J, Hamilton S, et al. A case of polyarteritis nodosa limited to the right calf muscles, fascia, and skin: a case report.Journal of Medical Case Reports (2011) 5:450.

5. Nakamura T, Tomoda K, Yamamura Y, et al. Polyarteritis nodosa limited to calf muscles: a case report and review of literature.Clin Rheumatol (2003) 22:149-153.

6. Jennette JC, Falk RJ, Bacon PA, et al. 2012 Revised International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference Nomenclature of Vasculitides.Arthritis Rheum (2013) 64:1-11.

7. Pagnoux C, Seror R, Henegar C, et al. Clinical features and outcomes in 348 patients with polyarteritis nodosa: a systematic retrospective study of patients diagnosed between 1963 and 2005 and entered into the French Vasculitis Study Group Database.Arthritis Rheum (2010) 62:616-626.

8. Gallien S, Mahr A, Rety F, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of skeletal muscle involvement in limb restricted vasculitis.Ann Rheum Dis (2002) 61:1107-1109.

9. Balbir-Gurman A, Nahir AM, Braun-Moscovici Y. Intravenous immunoglobulins in polyarteritis nodosa restricted to the limbs: case reports and review of the literature.Clin Exp Rheumatol (2007) 25 (1 suppl 44):S28-30.

10. Carron P, Hoffman IE, De Rycke L, et al. Case number 34: relapse of polyarteritis nodosa presenting as isolated and localized lower limb periostitis.Ann Rheum Dis (2005) 64:1118-1119.

11. Garcia-Porrua C, Mate A, Duran-Marino JL, et al. Localized vasculitis in the calf mimicking deep venous thrombosis.Rheumatology (Oxford) (2002) 41:944-945.

12. Hall C, Mongey AB. Unusual presentation of polyarteritis nodosa.J Rheumatol (2001) 28:871-873.

13. Iwamasa K, Komori H, Niiya Y, et al. A case of polyarteritis nodosa limited to both calves with a low titre of MPO-ANCA.Riyumachi (2001) 41:876-879.

14. Soubrier M, Bangil M, Franc S, et al. Vasculitis confined to the calves. Report of a case. Rev Rheum Engl Ed (1997) 64:414-416.

15. Esteva-Lorenzo FJ, Ferreiro JL, Tardaguila F, et al. Case report 866: pseudotumor of the muscle associated with necrotizing vasculitis of medium and small-sized arteries and chronic myositis.Skeletal Radiol (1994) 23:572-576.

16. Gardner GC, Lawrence MK. Polyarteritis nodosa confined to calf muscles. J Rheumatol (1993) 20:908-909.

17. Garcia F, Pedrol E, Casademont J, et al. Polyarteritis nodosa confined to calf muscles.J Rheumatol (1992) 19:303-305.

18. Hofman DM, Lems WF, Witkamp TB, et al.Demonstration of calf abnormalities by magnetic resonance imaging in polyarteritis nodosa.Clin Rheumatol (1992) 11:402-404.

19. Nash P, Fryer J, Webb J. Vasculitis presenting as chronic unilateral painful leg swelling.J Rheumatol (1988) 15:1022-1025.

20. Ferreiro JE, Saldana MJ, Azevedo SJ. Polyarteritis manifesting as calf myositis and fever.Am J Med (1986) 80:312-315.

21. Laitinen O, Haltia M, Lahdevirta J. Polyarteritis confined to lower extremities.Scand J Rheumatol (1982) 11:71-74.

22. Golding DN. Polyartertitis presenting with leg pains.Br Med J (1970) 1:277-278.

23. Eckel CG, Sibbitt RR, Sibbitt WL Jr, et al. A possible role for MRI in polyarteritis nodosa: the “creeping fat” sign.Magn Reson Imaging (1988) 6:713-715.

24. Watts RA, Scott DGI: Epidemiology of vasculitis. In: Vasculitis, (2008) 2nd edition. Edited by: Ball GV, Bridges, SL. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 7-22.

25. Mahr A, Guillevin L, Poissonnet M, Aymé S. Prevalences of polyarteritis nodosa, microscopic polyangiitis, Wegener's granulomatosis, and Churg-Strauss syndrome in a French urban multiethnic population in 2000: a capture-recapture estimate.Arthritis Rheum (2004) 51:92-99.