Article

Case Study: Would You Give This MS Patient Ocrelizumab?

Author(s):

Physicians debated whether they would prescribe the new MS drug to a patient.

Treating patients with multiple sclerosis is an exercise in coping with uncertainty. That much the physicians present for the “Debates Over Controversies in Multiple Sclerosis” discussion at the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers Annual Meeting could agree on.

The debate, which revolved around several case studies, involved moderator Dennis Bourdette, M.D., co-director of the MS Center Excellence-West; Benjamin Segal, M.D., of the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System; Olaf Stuve, M.D., PhD, of the VA North Texas Health Care System; and Mitchell Wallin, M.D., Director of the VA Center of Excellence-East. The debate took place on the meeting’s second day, Thursday, May 25, 2017.

For this exercise, physicians were asked to assume that the case study patients have MS. They were also encouraged to advocate for pro or con positions on the questions, with no middle ground.

Case 1 involved a patient with secondary progressive MS (SPMS) without evidence of recurrent focal inflammatory lesions. She asked the doctor, “Will that new medication, Ocrevus, help me?” The case details were as follows:

· “A 52-year-old woman who developed optic neuritis at 33 and a brainstem demyelinating lesion at 35. Diagnosis of relapsing MS was made and she was started on IFN-beta 1a.

· For the next 10 years, she was stable clinically and by MRI.

· About 46, she noted very slow worsening of her gait and cognitive problems. Progression continued despite trials of natalizumab and dimethyl fumarate.

· Exam notable for mild hemiparesis, an unsteady gait, and 25-foot timed walk of 7 seconds (EDSS 4.0).”

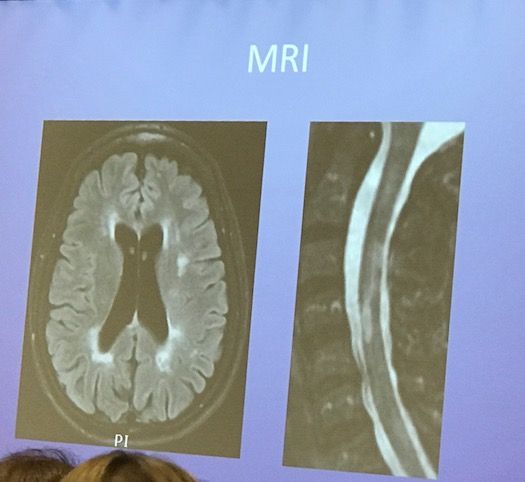

This was the patient’s MRI:

Wallin said ocrelizumab would not be a good option for this patient. From a high level, he formed his decision based on the facts that this middle-aged woman with onset in her early 30s has seen relapse activity stabilize. Furthermore, she had progressive MS earlier than expected and was unresponsive to treatments.

From an efficacy standpoint, Wallin highlighted that the patient has SPMS with stable MRIs. This phenotype, he said, wasn’t in the ocrelizumab trials.

“We can’t talk about the experience of this particular patient,” he said. “I would argue that she’s not representative of the trial population.”

Wallin also discussed the debatable nature of the progressive MS phenotype. How do we define it, he asked. Once you reach a 4 on the EDSS, the disease progresses in a similar fashion, he said.

“There’s no efficacy data that can be pulled that’s relevant to this case,” Wallin said.

Ocrelizumab also presents a safety hazard for this patient, he added. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) issues would have to be raised, he said, adding that it’s difficult to release ocrelizumab from the system.

“The risk of cancer is a real threat,” Wallin said, adding that the physician would have to evaluate the patient’s family history.

While ocrelizumab wouldn’t present any convenience-related issues, since it’s administered twice a year, it would be cost-prohibitive for some patients. The patient, Wallin said, may be a good candidate for an SPMS trial.

Segal spoke in support of administering ocrelizumab. He noted that there is a great deal of overlap between primary progressive MS (PPMS) and SPMS.

“Collectively, I think that data suggests so much overlap in the pathology,” he said.

He also cited a recent Italian study of B-cell follicles in SPMS. In this study, 40% of the autopsy specimens with SPMS have these follicles, which are largely composed of B-cells and likely contribute to disability. These B-cells can’t be seen on MRIs and are not associated with white-matter lesions, Segal said, but cortical lesions. He said that we know the patient was experiencing dementia, and therefore may have B-cell follicles causing formation of B-cell plaques.

“There is evidence that low-grade inflammation is occurring in SPMS,” he said.

Regarding the cancer risk, Segal said it’s too soon to gauge its severity. He noted that there is no statistically significant risk when comparing ocrelizumab to a placebo. Regarding the PML risk, he compared the drug to rheumatoid arthritis therapies that didn’t have a high risk of PML. It’s too soon to get an accurate indication of the PML risk in ocrelizumab, he said.

“I think there’s a lot of arguments to consider a trial of ocrelizumab,” he said.