Article

Colchicine Toxicity: Deadly Face of a Familiar Friend

Used for gout for centuries, colchicine is known to be peculiarly toxic at high doses. A new understanding of its potential for poisoning, deliberate or otherwise, merits attention to its often-underestimated risks.

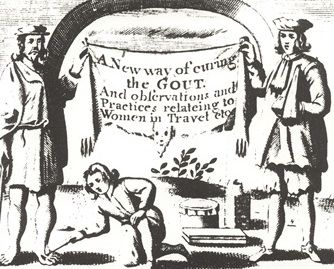

Colchicine has been used to treat gout since at least 550 AD.1 Its anti-inflammatory effects have been a focus in cardiology for a decade, but colchicine is also now considered a conventional treatment for acute pericarditis, regardless of cause. Animal studies suggest it may also have anti-atherosclerotic actions, a matter which needs to be clarified. First clinical results are also promising in patients with acute coronary syndromes.2

Perhaps because most patients with acute pericarditis are fairly young and have few comorbidities, adverse effects from colchicine for this indication have been surprisingly rare and mild. Cardiologists unfamiliar with the drug may be unaware of its volatile potential for toxicity, which has been documented since at least the 17th century and which I have summarized in a review in Anti-Inflammatory & Anti-Allergy Agents in Medicinal Chemistry.1

Although rheumatologists and primary care physicians use the drug routinely to treat gout, they too may be insufficiently alert to its deadly properties when ingested at high doses. The prevalence of life-threatening events (suicide and even perhaps murders) with colchicine is likely to be underestimated. It is possible commit suicide by taking only one month’s supply, especially in the case of renal impairment.

Mode of action:

Colchicine binds to tubulin, inhibiting polymerization of microtobules and acting as a “spindle poison” with an impact on all dividing or migrating cells.

Its main action in gout appears to be direct inhibition of migration of inflammatory cells including neutrophils. It may also have direct anti-inflammatory effects by inhibiting key signaling networks (mainly IL-1, IL-6, and TNF).

Pharmacokinetics:

Quickly absorbed in jejunum and ileum, it can enter almost all tissues and is excreted in breast milk.

Peak plasma levels are reached 2 hours after oral administration. However, colchicine can accumulate in monocytes to reach concentrations higher than plasma levels, making it difficult to predict concentrations in subsets of inflammatory cells.

Toxicity and adverse effects:

Life-threatening poisoning is rare, but the potential is worthy of concern. A dose of 40 mg can be lethal. There is no antidote.

Initial signs are similar to typical GI adverse effects. Multi-organ failure can follow within days.3, 4

Poisoning may produce life-threatening systemic effects:

• Nausea and vomiting

• Bone marrow suppression leading to sepsis

• Adult respiratory syndrome

• Direct cardiotoxicity

Treatment is supportive. Anti-colchicine antibodies have been shown effective,4 5 but are not commercially available.6

The focus on adverse effects of normal doses centers on pregnant women and fetuses. However, a recent large study found no increase in abortions or congenital malformations among offspring of women treated with colchicine for familial Mediterranean fever, compared to those of pregnant women with or without the disorder who had not taken colchicine.7Suggested contraindications:

• Avoid if possible: protease inhibitors, statins, cyclosporine, anticoagulants

• Contraindicated: Macrolide (telithromycin, azythromycin, clarithromycin, dirithromycin, erythromycin, josamycin, midecamycin, roxithromycin, troleandromycin, spiramycin), pristinamycine, verapamil

• Creatinine clearance < 30 mL/min (recent dosage)

• Severe hepatic dysfunction

• Uncontrolled or unexplained anemia, thrombocytopenia, or leucopenia

• If possible: Pregnancy, risk of pregnancy, breast-feeding

• History of an allergic reaction or significant sensitivity to colchicine constituents (rare)

Recommended monitoring for toxicity

Evaluate renal function and blood cell count before treatment, during the first month, and whenever initiating a new drug likely to induce interactions or if any clinical events occur involving hepatic dysfunction or renal impairment.

Also check the biology before the first treatment if the patient is likely to present with hepatic dysfunction.

References:

REFERENCES:

1. Roubille F, Kritikou E, Busseuil D et al. Colchicine: An Old Wine in a New Bottle? Anti-Inflammatory & Anti-Allergy Agents in Medicinal Chemistry (2012) Epub ahead of print.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed?term=23286287

2. Nidorf M. Low dose colchicine for secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease (The LoDoCo trial). Special science session American Heart Association 2012

3. Ozdemir R, Bayrakci B, Teksam O. Fatal poisoning in children: acute colchicine intoxication and new treatment approaches. Clin. Toxicol. (2011) 49: 739-743

4. Nagesh KR, Menezes RB, Rastogi P et al Suicidal plant poisoning with Colchicum autumnale, J. Forensic Legal Med. (2011) 18(6) 285-7

5. Flanagan RJ and Jones AL. Fab antibody fragments: some applications in clinical toxicology. Drug safety : Intern. J. Med. Toxicol. Drug Exp. (2004) 27(14): 1115-1133

6. Finkelstein Y, Aks SE, Hutson JR, et al Colchicine poisoning: the dark side of an ancient drug. Clin. Toxicol. (2010) 48(5): (5), 407-414

7. Ben-Chetrit E, Ben-Chetrit A, Berkun Y et al Pregnancy outcomes in women with familial Mediterranean fever receiving colchicine: is amniocentesis justified? Arthritis Care Res. (2010) 62 (2): 143-148