Article

Corticosteroids for painful shoulder conditions: Injection techniques

ABSTRACT: Corticosteroid/anesthetic injections may be useful diagnosticand therapeutic tools for painful shoulder conditions. The currentdogma is to avoid performing more than 3 injections over a9- to 12-month period, but this rule may be broken. The volume of localanesthetic typically injected might be insufficient for assessing accuracy.Data demonstrating significant advantages of one corticosteroidover another are scarce. For patients with diabetes mellitus, considera somewhat insoluble phosphoric corticosteroid. There is no consensusabout appropriate dosages and techniques.We recommend using1.5-inch 25-gauge needles for most injections. Re-evaluating provocativemaneuvers after each injection is important. The patient's estimatedpain relief always should be documented.Two approaches toinjection may be used, an advanced/detailed method and abasic/quick method. (J Musculoskel Med. 2008;25:375-386)

ABSTRACT: Corticosteroid/anesthetic injections may be useful diagnostic and therapeutic tools for painful shoulder conditions. The current dogma is to avoid performing more than 3 injections over a 9- to 12-month period, but this rule may be broken. The volume of local anesthetic typically injected might be insufficient for assessing accuracy. Data demonstrating significant advantages of one corticosteroid over another are scarce. For patients with diabetes mellitus, consider a somewhat insoluble phosphoric corticosteroid. There is no consensus about appropriate dosages and techniques. We recommend using 1.5-inch 25-gauge needles for most injections. Re-evaluating provocative maneuvers after each injection is important. The patient's estimated pain relief always should be documented. Two approaches to injection may be used, an advanced/detailed method and a basic/quick method. (J Musculoskel Med. 2008;25:375-386)

Corticosteroid/anesthetic injections may be useful diagnostic and therapeutic tools for physicians treating patients with painful shoulder conditions. When clinicians have a clear understanding of the local and systemic effects, indications, contraindications, appropriate doses and dose ranges, and methods for injecting corticosteroid/ anesthetic mixtures, they may administer these injections safely and effectively.

This 3-part article describes the diagnostic and therapeutic uses of corticosteroid/anesthetic injections for painful shoulder conditions. The first part ("The use and misuse of injectable corticosteroids for the painful shoulder," The Journal of Musculoskeletal Medicine, February 2008, page 78) covered the mechanism of action, current preparations, indications and contraindications, adverse effects, misuses, and lack of uniform standards of care. In the second part ("Injectable corticosteroids for the painful shoulder: Patient evaluation," The Journal of Musculoskeletal Medicine, May 2008, page 236), we discussed physical examination and radiographic evaluation procedures for determining when to inject corticosteroids. This third part describes specific injection techniques and approaches and offers algorithms for evaluation and injection.

FREQUENCY, DOSE, TYPE, AND LOCATIONS

The current dogma in corticosteroid injection for most shoulder conditions is to avoid performing more than 3 injections over a 9- to 12-month period. However, this rule may be broken.

We often "reset" the injection count when pain recurs after a 12-month injection-free and, typically, pain-free interval. If there is significant pain during the 12 months, however, starting a "new" series of corticosteroid injections may not be appropriate. For example, recurrent pain localized to the subacromial (SA) area may require a different treatment strategy, including re-examination with additional diagnostic imaging (eg, MRI), giving only 1 more injection (maybe only local anesthetic for diagnostic purposes), and resumption of physical therapy.

Can and should injections be given when there is a rotator cuff tear? They may be useful in treating middle-aged to older patients who have acute or subacute cuff tears that are potentially operative. In fact, animal studies support the idea that delaying surgery while nonoperative measures are attempted does not necessarily compromise a good surgical outcome.1

By decreasing inflammation resulting from the SA bursitis that accompanies a rotator cuff tear, corticosteroid injections may provide short-term pain relief. In some cases, physical therapy could then be started. In a few patients, the relief is at an acceptable level and surgery may be avoided; in these cases, especially when the tear is posttraumatic, we try to make a definitive decision about whether to perform surgery within 2 to 3 months of injury. In addition, corticosteroids should be used judiciously because they may weaken tendons.

In contrast, when a chronic tear is present and is considered nonoperative and where replacement arthroplasty is not an option, we allow 2 or 3 injections per year. Again, this usually is done in older patients (eg, older than 70 years) who want to avoid surgery. In some of these cases, the diagnosis is rotator cuff tear arthropathy.

Injection volumes/doses

In many cases, the volume of local anesthetic typically injected with corticosteroid into some regions of the shoulder might be insufficient for assessing injection accuracy. For example, in 1983, Neer2 described the SA impingement "test" as injecting 10 cc of 1.0% lidocaine into the SA bursa. This test is based on comparison of pain elicited from the impingement sign preinjection with pain elicited 10 minutes postinjection. It also may be used to help determine whether the cause of limited range of motion is shoulder pain or weakness attributed to a rotator cuff tear.3

Neer4 found that these techniques were "the most valuable method for separating impingement lesions from other causes of chronic shoulder pain." The impingement test also has been used to predict surgical outcomes.5-8 Therefore, we use similarly "large" volumes of anesthetic in our diagnostic/ therapeutic injections.

Using large volumes of corticosteroid/ anesthetic solution and injecting in the posterior third, middle, and anterior third of the SA space may help prevent the solution from being localized into "compartments" that might occur normally or be associated with bursal adhesions.9 However, in our recent survey of 169 physicians, less than 5 mL of local anesthetic was used for SA injections by 73% of primary care sports medicine physicians and physical medicine and rehabilitation physicians (PCSMs/PMRs), 100% of rheumatologists, and 53% of orthopedic surgeons.10 The range of corticosteroid dose equivalents for SA joint injections also was broad (eg, 40 to 120 mg of some agents).

In addition, 29% of PCSMs/PMRs, 44% of rheumatologists, and 41% of surgeons actually exceeded recommended corticosteroid doses for the acromioclavicular (AC) joint. For the SA bursa and glenohumeral (GH) joint, however, only 1% to 4% of the physicians reported doses that exceeded recommended ranges. These data reflect a lack of consensus about how much corticosteroid/ anesthetic should be injected into various areas of the shoulder.

Type of corticosteroidGenerally healthy patients. For most orthopedic indications, data demonstrating significant advantages of one corticosteroid over another are scarce. In some circumstances, however, specific corticosteroids might be preferable because of variations in their solubility or potency or both.

For example, some physicians have reported that they use a combination of fast-acting (more soluble) and slow-acting (less soluble) corticosteroids, such as dexamethasone and triamcinolone acetonide, respectively, for SA injections. If triamcinolone acetonide is the preferred corticosteroid, supplementing its use with dexamethasone will enhance the onset and duration of the anti-inflammatory effect-dexamethasone is quite soluble and has more rapid onset than triamcinolone acetonide, and the effects of dexamethasone usually taper off after 3 or 4 days, when triamcinolone acetonide begins to exhibit its effects.

Patients with diabetes mellitus (DM). Considering a somewhat insoluble phosphoric corticosteroid for these patients is advisable. Although published data supporting this approach are limited, our experience has shown a reduction in fluctuations in fingerstick blood glucose measurements with the use of these corticosteroids. In theory, phosphoric corticosteroids (eg, dexamethasone phosphate, betamethasone sodium phosphate, and prednisone phosphate) exhibit fewer systemic effects because they act more rapidly and reduce the possibility of significant systemic spread (eg, blood glucose levels are less affected).

After administering corticosteroid injections, we advise our patients with DM to monitor their blood glucose levels regularly for 1 week. The first 2 or 3 days are most critical because elevated blood glucose levels are more likely to occur then. We have not encountered significant problems with glucose control when patients with DM are made aware of this possibility and when they make adjustments (which could require 2-fold or greater increases in their typical doses) in their oral and injectable hypoglycemic medications.

PRINCIPLES OF INJECTION

There is no consensus about appropriate dosages and techniques for injecting corticosteroids for painful shoulder conditions.11 Tallia and Cardone12 and Saunders13 discussed basic injection techniques for the AC and GH joints, SA space, scapulothoracic bursa, and biceps tendon sheath. Some are incorporated into the methods that we use in our shoulder specialty practice described below.

Distracting patients from pain

Converse with the patient about his or her interests and hobbies. Also, very briefly describe the procedure you will be performing, including a warning about the ensuing needle prick. Doing so helps the patient feel like he has some control and knows what to expect. Frequently ask the patient how he is doing (eg, "Is it hurting too much?").

Spray a vapocoolant (skin refrigerant) away from the injection site (eg, mid-arm) to distract the patient and allow him to feel its cooling action so that he can anticipate how it feels when it is sprayed onto the injection site. Then spray the fluid directly onto the injection site until blanching occurs, indicating that numbing of the skin is sufficient.

Immediately after spraying the vapocoolant, drip 2 to 3 rivulets of lidocaine just below the injection site and let them trickle down the patient's arm.These rivulets are effective in diverting the patient's attention from the injection.Then inject the overlying skin and subcutaneous tissue with lidocaine. The needle remains in the skin and the barrel of the syringe is switched for the one containing the anesthetic/ corticosteroid mixture.

Use small needles

We recommend using 1.5-inch (about 2.8 cm) 25-gauge needles for most injections (a notable exception is GH joint injection, for which a 20- or 22-gauge needle may be used). The 25-gauge needles are stiff enough to be moved around inside the injection site but small enough to avoid inducing excessive pain. If for whatever reason a 22- gauge or larger needle is used, we suggest numbing the area first with a 25- to 27-gauge needle.

Usually, four 25-gauge needles (for most locations) and one 18- gauge spinal needle (for the GH joint) should be available for most corticosteroid injections. Two 25- gauge needles should be on syringes, and 2 should be placed aside for possible biceps sheath injection or repeated injections using different needle orientations. Syringes with 12.5 mL capacities should be used for injection into the SA space, GH joint, and scapulothoracic bursa.

Injection order

Because many patients with shoulder pain have a subacromial impingement syndrome-often with AC arthritis and less frequently with GH or biceps tendon pathology-we usually consider performing injections in the following order: (1) SA space, (2) AC joint, (3) biceps sheath, (4) GH joint. If after the SA space and AC joint are injected the percent pain relief within 10 minutes is lower than 50%, we consider performing only diagnostic (local anesthetic) injections into the biceps sheath, GH joint, or other periarticular location. If pain relief then improves significantly, additional anatomical locations may be injected with a corticosteroid 2 to 4 weeks later.

We inject both the SA space and AC joint during the same clinic visit in about 50% of our injected patients because we typically see middle-aged patients. If the AC joint is injected before the SA space, then the SA space may be injected unintentionally by inadvertent entry through the AC joint, thus confusing the task of isolating the source of pain. For patients with advanced GH osteoarthritis and mild or absent SA impingement-type symptoms, we recommend injecting the GH joint first and then, if the percent relief is lower than 50%, continuing with SA and AC injections. In this situation, the biceps sheath should not be injected because in most cases the corticosteroid is expected to trickle into the biceps sheath from the GH joint.

Re-evaluate provocative maneuvers

After each injection, re-evaluating provocative maneuvers is important. The following procedure is recommended:

• Passively perform the maneuvers on the patient (usually through about 60% to 80% of full range of motion).

• Wait 20 to 30 seconds and then have the patient actively perform the same maneuvers.

• Passively perform the maneuvers again.

• Wait 20 to 30 seconds and then have the patient actively perform the maneuvers again (evaluate percent relief during this step; 3 to 5 minutes should have gone by).

This procedure helps distribute the corticosteroid and anesthetic, in theory allowing for more accurate estimation of pain relief. Clinicians should note that coexisting bursitis, arthritis, tendinitis, shoulder instability, scapulothoracic bursitis, or cervical pathology may confound these interpretations of percent pain relief.14

Strength testing also should be done after the local anesthetic has taken effect because there may be notable improvements in supraspinatus strength. A positive drop-arm maneuver test result also can improve notably. In fact, when this occurs we often steer away from ordering an MRI scan and instead order physical therapy while adopting a "wait and see" approach to allow time to find out whether improvement is sustained. In these cases, what initially appeared to be stage 3 SA impingement (with a full-thickness rotator cuff tear) might be stage 2 (no cuff tendon tear) or stage 3 with a partial but possibly nonoperative cuff tear.

Documenting and charting the level of pain relief

Documenting the patient's estimated pain relief is important for all injections; we use a percentage system (0%, no relief; 100%, full relief) or a 10-cm Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) (0 cm, no pain; 10 cm, worst pain). The patient typically should have a minimum of 70% relief (eg, a reduction from 10 to 3 cm on a VAS) before completing injection; 90% to 100% relief is preferable. Documenting the patient's final total percent relief in the medical record by 15 minutes after the injection is important. If there is uncertainty about this value or the patient may need more time for the local anesthetic to take effect, have him telephone the clinic 30 to 45 minutes after he leaves to report his maximum percent relief.

We recently showed that temporal variations can occur after a Neer impingement type of test14; this should be kept in mind, especially for patients who have difficulty in estimating percent pain relief. We also try to determine whether pain relief occurs for one provocative maneuver but not another.

If more than 70% relief is obtained within a few minutes of the SA or AC injection, have the patient estimate his final percent relief when he leaves the examination room. For SA impingement syndromes, Mair and associates6 recommended operating only on the patients who have pain relief exceeding 75% from preoperative corticosteroid/anesthetic SA injections. We typically do not recommend operating on patients who do not have at least 50% relief and cannot state that they would be happy with their level of relief by 15 to 40 minutes after the injection. However, some patients with more than 50% relief state that they would be happy if surgery would provide this lower level of relief. These parameters reflect the prognostic utility of corticosteroid/anesthetic injections.

Adjusting doses for smaller-than-average patients

For patients who are notably smaller than average, we recommend using about a 30% lower dose/volume of corticosteroid and anesthetic (eg, for a 120-lb woman, use 6 to 8 mL total solution for the SA injection rather than 10 to 11 mL). By contrast, we do not exceed recommended dose ranges for very large patients.

INJECTION TECHNIQUES

Preparation and sterile technique

Materials helpful for performing shoulder injections include the following:

• Mayo stand. Keep injectables on this or on a nearby countertop. Keeping injection paraphernalia off the examination table is important should the patient faint or need to lie down, and it secures a place for a sterile field.

• Povidone-iodine prep; sterile alcohol swabs. Standard prep technique is followed (alcohol, povidoneiodine, inject when the prep is dry). We usually also place an alcohol swab on the prepped injection site. This helps lubricate the skin for localizing frequently injected areas, such as the AC joint and SA space.

• Assistant. Have an assistant in the room to help with injection (mostly to observe for fainting and comfort the patient).

• Gown. Ideally, women should wear gowns that allow for complete evaluation of their shoulders (because active and passive shoulder movements are necessary) while also allowing for modesty.

ADMINISTERING THE INJECTION

Two approaches

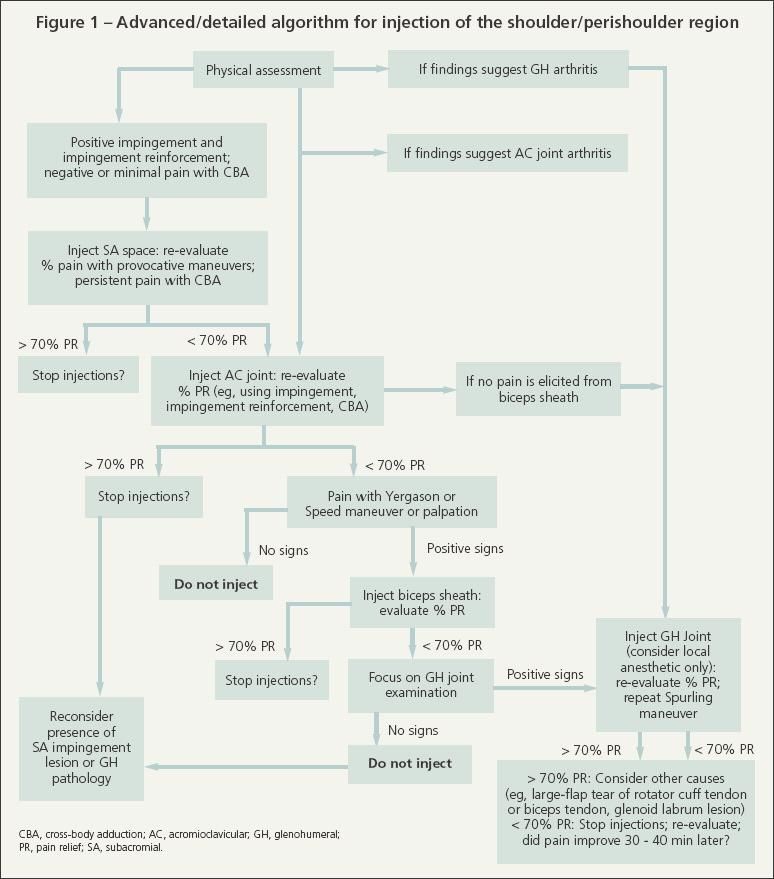

The advanced/detailed method is for physicians or other health care providers who have allotted sufficient time or who desire to follow sequential steps for making the diagnosis and managing more complex painful shoulder conditions (2 or more anatomical sources of pain) (Figure 1). This method may be used more often by orthopedic specialists interested in surgical planning or by nonsurgical specialists who manage complex shoulder problems. Many providers may find the approach impractical because of time constraints or a heavy patient load, and others may not be trained adequately to make a diagnosis for less common shoulder conditions.

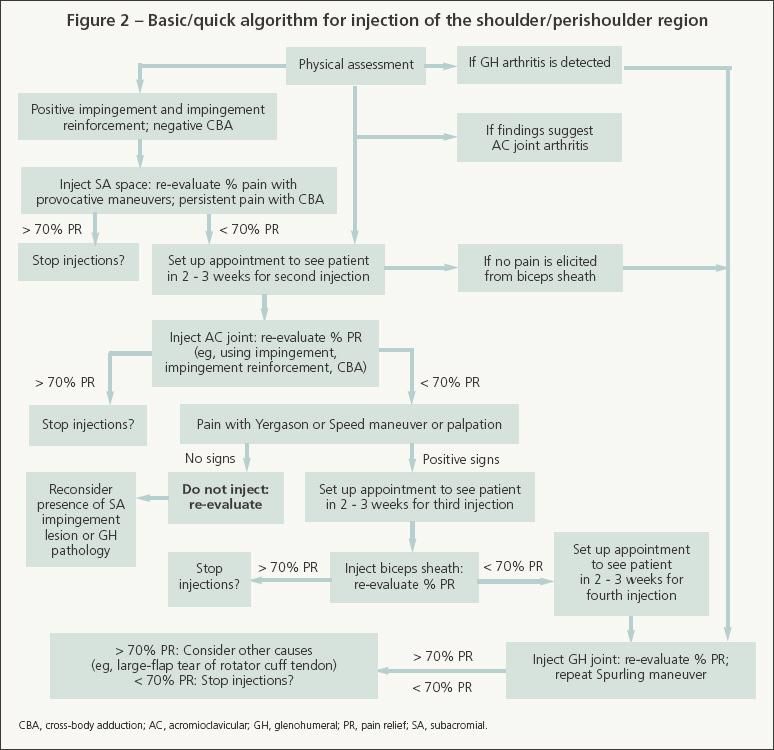

The basic/quick method is a more practical approach-administer only 1 injection and then see the patient 2 to 3 weeks later for reevaluation and a possible second injection (Figure 2). Because most shoulder problems are forms of SA impingement syndromes, patients with positive impingement signs and a negative cross-body adduction maneuver result should receive only the SA injection and be instructed to follow up in 2 to 3 weeks. If there are obvious signs of a more complicated problem, the patient could be referred to an orthopedic surgical or nonsurgical musculoskeletal specialist. If significant pain persists after 2 weeks, consider administering a different injection or giving another SA injection (with local anesthetic only and with a different needle orientation) or refer the patient to an orthopedic shoulder specialist.

SA injection

Begin with SA injection if physical findings suggest impingement syndrome. Skip to GH injection if significant GH arthritis is detected.

For SA injection, start with the syringe containing only 5 mL of 1% lidocaine. Palpate the SA space, which is easier to localize when the patient relaxes his elbow, arm, and shoulder. Infuse 1.5 to 2 mL of lidocaine between the skin and SA space; then infuse 1 mL into the SA space. Leaving the needle in place, change only the syringe barrel to the one containing the corticosteroid/anesthetic solution, and then inject the remaining solution into the SA space in 2- to 2.5-mL boluses in different directions. There should be minimal to low resistance. If there is significant resistance, pull back and redirect the needle. Significant resistance may indicate extensive bursitis or inadvertent injection of the rotator cuff tendon, deltoid fascia, or other tissues.

We recommend beginning with the lateral or posterolateral approach to the SA space, but additional approaches may be needed: anterior, anterolateral, superolateral, and anteromedial. Also, the injection approach could be superior through the AC joint. Adjust needle direction based on the relative ease of palpating the SA area and radiographic examination of acromial morphology-moderate to severely "hooked" acromia warrant avoiding anterior and anterolateral approaches.

The most common error in SA injection is starting too high (ie, the needle strikes the acromion), which can cause pain. If this occurs, pull the needle out of the skin, reanesthetize the area well, make sure that the patient relaxes his arm, reinsert the needle 10 to 15 mm below the previous injection site and, as needed, redirect the needle.

After the injection, remove the needle and syringe and evaluate the patient's percent pain relief about 5 to 10 minutes later while he is performing impingement maneuvers. If the patient reports significant relief with these maneuvers but still experiences pain with cross-body adduction (less than 70% total pain relief), proceed with AC joint injection. For the basic/quick method, the AC joint may be injected during a follow-up visit.

AC joint injection

Anesthetize the skin with 0.5 to 1 mL of lidocaine, then switch the syringe barrel and infuse the AC joint with 2.25 to 2.5 mL of the corticosteroid/ anesthetic solution. In some cases (typically because of arthritis), the AC joint must be infused from 2 directions (anterosuperior and posterosuperior). If, however, the radiograph of the AC joint looks normal, consider injecting only local anesthetic into the AC joint.

If pain relief does not occur, the pain might actually be from the sternoclavicular joint or SA area. This finding reflects the somewhat poor sensitivity of the cross-body adduction maneuver (about 23%) and correlates with the observation that a high rate of asymptomatic patients have significant AC pathology on MRI scans.15

Palpate the AC joint before administering the injection. Use the approach in which the palpable depression (or sulcus) of the AC joint is most obvious; in our experience, this typically is posterior. However, missing and hitting bone is not uncommon. When this occurs, patients do not report the "high" magnitude of pain that occurs when the acromion is inadvertently struck during SA injection. If it does occur, redirect until the fluid infuses into the AC joint with little resistance.

When injecting the SA space or AC joint, any residual corticosteroid/ anesthetic solution (about 1 to 2 mL) may be injected into the SA bursa through the AC joint. This is done as needed to enhance infusion into the SA bursa when pain relief is less than 70% after the initial SA injection.

If at least 70% relief is achieved after the AC and SA injections, evaluate the patient within 3 minutes before he puts on his shirt) and again within 10 to 15 minutes (before he leaves the examination room). Evaluate all relevant specific maneuver results (eg, Neer impingement, Hawkins-Kennedy impingement reinforcement, and cross-body adduction). Obtain and document total percent relief, as well as percent relief for each specific maneuver.

Sometimes it takes longer for the local anesthetic to exhibit its full effect or, in some cases, the patient is uncertain of his percent relief. In these cases, the patient is instructed to telephone the clinic 30 to 45 minutes after he leaves to report his final total percent relief. However, most patients have 70% relief within 10 minutes of the injection.

Biceps tendon sheath injection

If less than 70% relief is obtained with AC and SA injections, palpate the biceps tendon by internally rotating the shoulder 5° to 10° to place the tendon at the anterior aspect of the shoulder (biceps/shoulder rotation maneuver). Also perform the Yergason and Speed maneuvers. If significant pain is elicited with 1 or more of these maneuvers, consider injecting the biceps sheath with only local anesthetic for diagnostic purposes. If this provides significant relief, a corticosteroid could be injected in the sheath at a follow-up visit.

When injecting the biceps sheath, we recommend penetrating until the needle hits bone and then pulling out the needle and injecting 1 to 2 mL (as long as there is minimal resistance); then redirect the needle (upward and downward) and inject the final amount in these 2 directions. About 3 small boluses are injected. Do not inject if there is resistance because this could result in an intratendon injection, which can lead to tendon rupture.

This method differs from that used to inject corticosteroids around a tendon or ligament without a sheath (eg, tendons near the wrist or Achilles tendon). In these cases, the solution is not injected as a bolus because this could penetrate the tendon, which could lead to tendon rupture. Instead, a "peppering" technique is used-the same skin puncture is used and the needle is backed out slightly and reoriented before injecting small amounts of solution.

GH joint injection

Even in our shoulder specialty clinic, the GH joint is injected less frequently than the SA bursa and AC joint. The GH joint should be injected with the corticosteroid/anesthetic solution (eg, 1 mL of methylprednisolone acetate, 2.5 mL of lidocaine) before the SA and AC regions if clinical examination suggests that this joint is the primary source of pain (crepitus or pain with internal/external rotation with the patient's arm at his side, decreased range of motion, and significant arthritis on radiographs). However, if the SA joint, AC joint, or biceps sheath is injected first and the examiner subsequently determines that GH pathology probably is the source of pain, local anesthetic may be injected into the GH joint for diagnostic purposes.

The GH may be difficult to inject-it requires more practical experience than injections in other locations. We prefer injecting into the posterior aspect of the joint.

The examiner palpates and then starts the injection at 1.5 to 2 cm inferior and medial to the posterolateral acromion. The needle is directed toward the coracoid, which can be palpated with the examiner's index finger during the injection. The needle also is directed superiorly about 15° to 20°. Two to 3 mL of lidocaine is first injected with a 25-gauge needle from the skin toward the joint. An 18-gauge needle is then used to enter the joint, and 1 or 2 mL of lidocaine is infused.

The lidocaine should flow in easily if the needle tip is intra-articular. This is the most important part of ensuring a successful GH injection. When the inflow of lidocaine is without resistance, the barrel is changed and the syringe barrel with the corticosteroid/anesthetic solution is attached to the needle and the entire volume is injected.

Do not inject the biceps sheath if the routine sequence (SA, AC, GH) is followed and there is less than 70% relief with AC/SA injections and no pain elicited from the biceps tendon/sheath. Instead, consider injecting the GH joint. Look again for clinical evidence of GH joint arthritis.

For example, if crepitation is felt or pain is elicited during shoulder rotation with the elbow at the patient's side, or if significant osteoarthritis is seen on standard radiographs, inject the GH joint with only local anesthetic (up to 2.5 mL of lidocaine). If the patient experiences significant percent relief after the lidocaine injection and if no rotator cuff tear is present, corticosteroid could be injected into the GH joint. In our practice, when we think that we have missed the joint, we occasionally send the patient to a radiologist for a fluoroscopically guided intra-articular GH joint injection.

If a full-thickness rotator cuff tear is present or suspected and the SA space has already been injected, some corticosteroid from the SA space would be expected to enter the GH joint. For this situation, use 11 mL of the corticosteroid/anesthetic solution that typically is used for SA injection and inject half in the SA space and half in the GH joint. Alternatively, if the GH injection is the only injection given (eg, for moderate to severe arthritis), the corticosteroid and 5 mL of anesthetic solution may be infused; this dosing also applies for rotator cuff tear arthropathy.

An additional important consideration for GH injections, especially for rotator cuff tear arthropathy, is to aspirate these locations with a large-bore needle to evacuate the effusion that often accompanies this condition. Doing so helps avoid diluting the corticosteroid.

Scapulothoracic injection

For scapulothoracic bursa injections, we use the same proportions and total volume of corticosteroid/anesthetic used in SA injection. The scapulothoracic injection is given in both superomedial and medial approaches. The needle should have a "low pitch" (nearly paralleling the plane of the scapula); patients may be in a sitting position for this injection. Anesthetize the skin down to the bone; intentionally make contact with the bone so that the needle can be pushed beneath it without penetrating too deeply. In addition to maintaining a low pitch, this helps avoid penetrating the thoracic cavity.

OTHER CONSIDERATIONS

Residual pain

If less than 70% relief is achieved with adequate SA space, AC joint, biceps sheath, and GH joint injections, consider other causes of shoulder pain. These may include a large-flap tear of the cuff tendon, a biceps tendon or glenoid labrum lesion, cervical radiculitis, scapulothoracic bursitis, coracoid impingement, sternoclavicular arthritis, and thoracic outlet syndrome.

Injection accuracy

In a study of rheumatologists who used radiopaque "dye" to track injection accuracy during local corticosteroid injections into the shoulder region, only 14 of 38 (37%) procedures were placed accurately; SA injections were more difficult than GH injections.16 Outcomes in patients who received accurately placed injections were superior to those in patients who did not.

In view of these study findings, considering whether "ineffective" corticosteroid/anesthetic injections that had been given to referred patients or those seen in follow-up were accurate is important. We often suspect that ineffective injections in patients referred to our shoulder specialty clinic actually were inadequate or inaccurate. In these cases, we often repeat injections.

Follow-up instructions

For most shoulder conditions, the corticosteroid may begin to take effect as quickly as 24 hours after the injection. Usually, however, the patient does not experience significant improvement until after 3 to 5 days. If NSAIDs are being taken for isolated shoulder pain at the time of the injection, they could be continued for 3 to 5 days postinjection.

Patients should be made aware of this time course so that they will not be disappointed if significant pain relief is not experienced within the first few days postinjection. They also are informed that increased pain caused by corticosteroid flare might occur within 24 hours of the injection.

References:

References

- 1. Koike Y, Trudel G, Curran D, Uhthoff HK. Delay of supraspinatus repair by up to 12 weeks does not impair enthesis formation: a quantitative histologic study in rabbits. J Orthop Res. 2006;24:202-210.

- 2. Neer CS 2nd. Impingement lesions. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1983;173:70-77.

- 3. Arroyo J, Flatow EL. Management of rotator cuff disease: intact and repairable cuff. In: Iannotti JP, Williams GR Jr, eds. Disorders of the Shoulder: Diagnosis and Management. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007:31-56.

- 4. Neer CS II. Cuff tears, biceps lesions, and impingement. In: Neer CS II, ed. Shoulder Reconstruction. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1990:41-142.

- 5. Altchek DW, Warren RF, Wickiewicz TL, et al. Arthroscopic acromioplasty: technique and results. J Bone Joint Surg. 1990;72A:1198-1207.

- 6. Mair SD, Viola RW, Gill TJ, et al. Can the impingement test predict outcome after arthroscopic subacromial decompression?

J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2004;13:150-153.

- 7. Patel VR, Singh D, Calvert PT, Bayley JI. Arthroscopic subacromial decompression: results and factors affecting outcome.

J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1999;8:231-237.

- 8. Yamaguchi K, Flatow EL. Arthroscopic evaluation and treatment of the rotator cuff. Ortho Clin North Am. 1995;26:643-659.

- 9. Strizak AM, Danzig L, Jackson DW, et al. Subacromial bursography: an anatomical and clinical study. J Bone Joint Surg. 1982;64A:196-201.

- 10. Skedros JG, Hunt KJ, Pitts TC. Variations in corticosteroid/anesthetic injections for painful shoulder conditions: comparisons among orthopaedic surgeons, rheumatologists, and physical medicine and primary-care physicians. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2007;8:63.

- 11. Rozental TD, Sculco TP. Intra-articular corticosteroids: an updated overview. Am J Orthop. 2000;29:18-23.

- 12. Tallia AF, Cardone DA. Diagnostic and therapeutic injection of the shoulder region. Am Fam Physician. 2003;67:1271-1278.

- 13. Saunders S. Injection Techniques in Orthopaedic and Sports Medicine. 2nd ed. New York: Saunders; 2002.

- Skedros JG, Pitts TC. Temporal variations in a modified Neer impingement test can confound clinical interpretation. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;460:130-136.

- 14. Stein BE, Wiater JM, Pfaff HC, et al. Detection of acromioclavicular joint pathology in asymptomatic shoulders with magnetic resonance imaging. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2001;10:204-208.

- 15. Eustace JA, Brophy DP, Gibney RP, et al. Comparison of the accuracy of steroid placement with clinical outcome in patients with shoulder symptoms. Ann Rheum Dis. 1997;56:59-63.