Article

COVID-19: Protecting First Responders and Bystanders During Emergency CPR

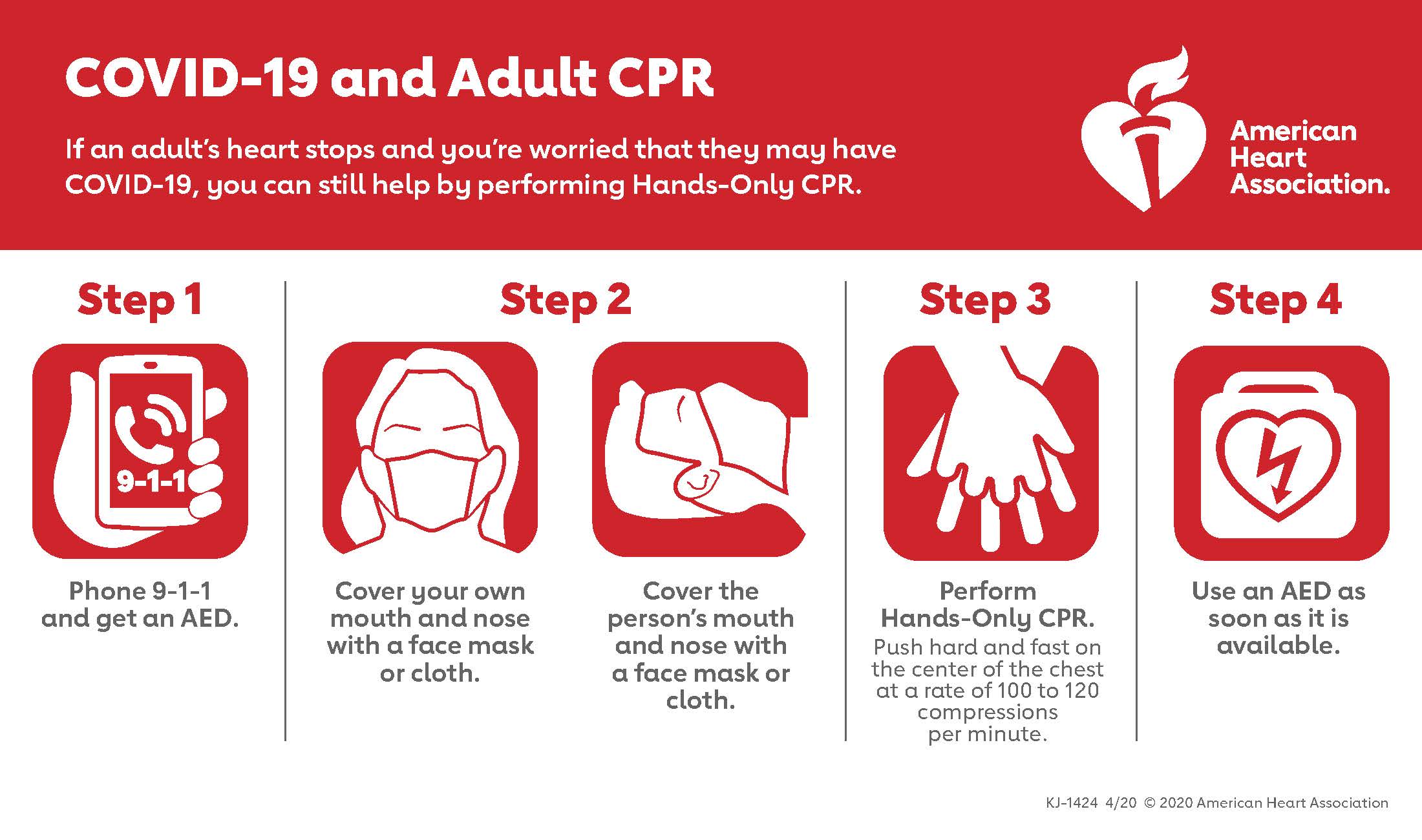

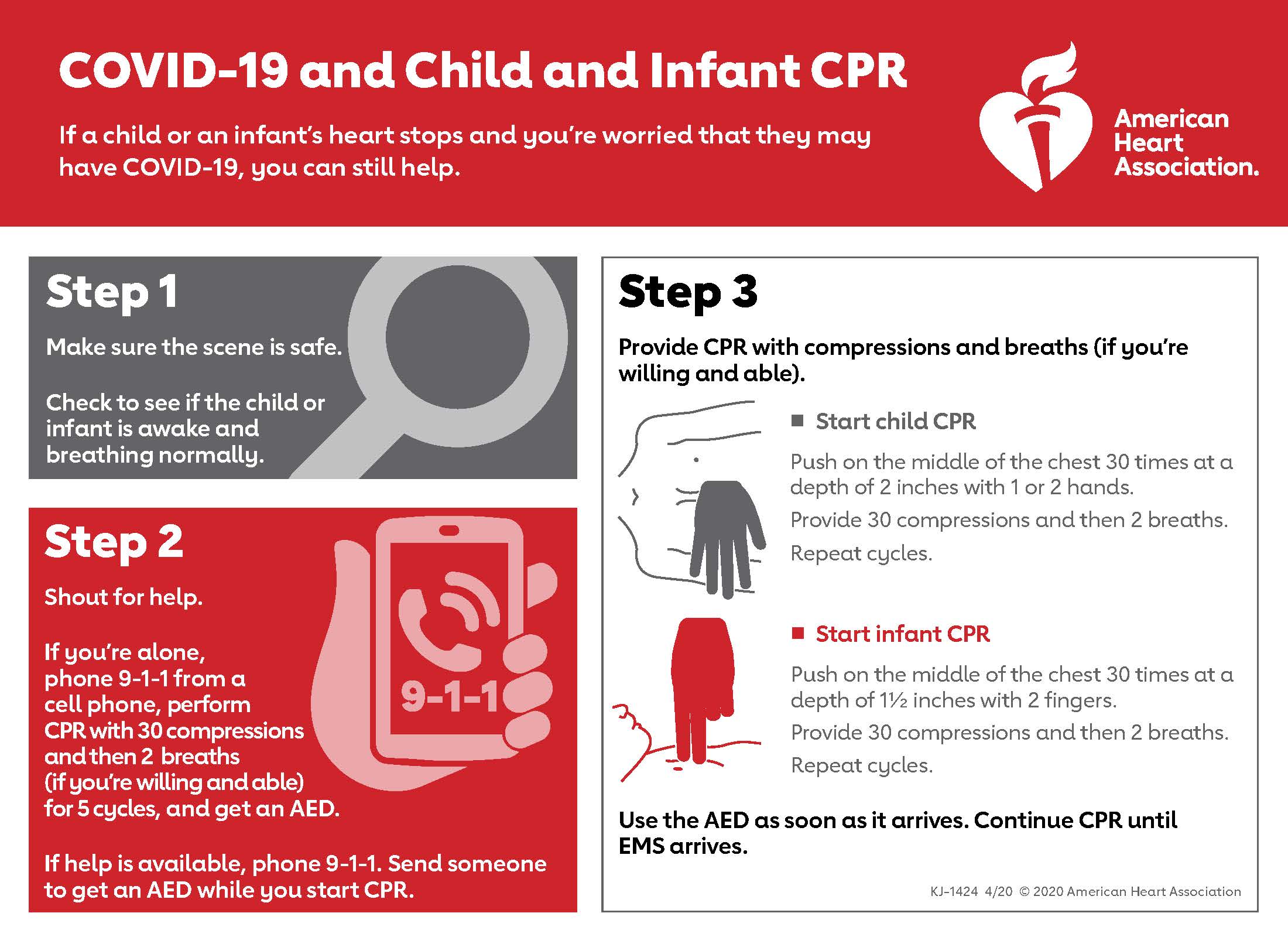

In the setting of the COVID-19 global pandemic, the existing American Heart Association (AHA) cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) guidelines are no longer appropriate. Rescue workers can no longer focus solely on the needs of the patient, but instead they must strike a balance between patient needs and protecting their own health and safety. The AHA has published new recussitation guidelines for rescue workers treationg victims of cardiac arrest with suspected COVID-19.

In the setting of the COVID-19 global pandemic, the existing American Heart Association (AHA) cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) guidelines are no longer appropriate. Rescue workers can no longer focus solely on the needs of the patient, but instead they must strike a balance between patient needs and protecting their own health and safety.

The AHA, in collaboration with the American Academy of Pediatrics, American Association for Respiratory Care, American College of Emergency Physicians, The Society of Critical Care Anesthesiologists, and American Society of

Anesthesiologists, and with the support of the American Association of Critical Care Nurses and

National EMS Physicians, has crecently compiled interim guidance to help rescuers treat victims of

cardiac arrest with suspected or confirmed COVID-19, in order to aid emergency workers and bystranders in safely treating COVID-19 positive patients.

According to the guidelines published in the AHA jouranl Circulation, "COVID-19 is highly transmissible, particularly during resuscitation, and carries a high morbidity and mortality. Approximately 12%-19% of COVID-positive patients require hospital admission and 3%-6% become critically ill. 2-4 Hypoxemic respiratory failure secondary to acuterespiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), myocardial injury, ventricular arrhythmias, and shock are common among critically ill patients and predispose them to cardiac arrest,5-8 as do some of the proposed treatments, such as hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin, which can prolong the QT.9 With infections currently growing exponentially in the United States and internationally, the percentage of cardiac arrests with COVID-19 is likely to increase."

Healthcare workers are already the highest risk profession for contracting the disease the authors say. A risk whhich is further compounded by worldwide shortages of personal protective equipment (PPE), and the added risks inherent to resuscitations. For example, CPR involves performing numerous aerosol-generating procedures, including chest compressions, positive pressure ventilation, and establishment of an advanced airway. During those procedures, viral particles can remain suspended in the air with a half-life of approximately 1 hour and be inhaled by those nearby. Furthermore, resuscitation efforts require numerous providers to work in close proximity to one another and the patient, and, lapses in infection control practices are more likely during high-stress emergent events.

A brief summary of the full guidelines includes:

- Before entering the scene, all rescuers should don PPE to guard against contact with both airborne and droplet particles.

- Limit personnel in the room or on the scene to only those essential for patient care.

- Clearly communicate COVID-19 status to any new providers

- Consider replacing manual chest compressions with mechanical CPR devices to reduce the number of rescuers required

- Attach a HEPA filter securely, if available, to any manual or mechanical ventilation

device in the path of exhaled gas before administering any breaths.

- Connect the endotracheal tube to a ventilator with aHEPA filter, when available

- Minimize the likelihood of failed intubation attempts by assigning most experienced provider

- Video laryngoscopy may reduce intubator exposure to aerosolized particles and

should be considered, if available

- Healthcare systems and EMS agencies should institute policies to guide front-line

providers in determining the appropriateness of starting and terminating CPR for

patients with COVID-19, taking into account patient risk factors to estimate the

likelihood of survival.

- It is reasonable to consider age, comorbidities, and severity of illness in determining the

appropriateness of resuscitation and balance the likelihood of success against the risk to

rescuers and patients from whom resources are being diverted

These guidelines were adapted from the original paper. Providers can find the full guidelines HERE.