Article

ECG Challenge: Encountering Extrasystoles

Author(s):

What do you suspect in a 45-year-old woman presenting with hypotension, bradycardia, and no significant medical history? ECG, here.

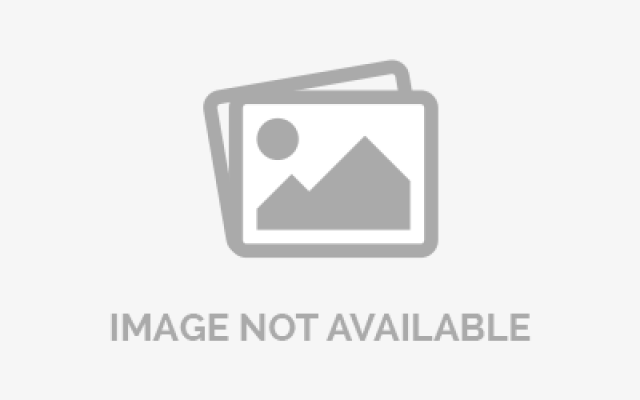

A 45-year-old woman with no prior medical issues presents to her family physician for several weeks of progressive fatigue and dyspnea on exertion. Vital signs taken with an automatic blood pressure (BP) cuff show a BP of 85/56 mm Hg and heart rate of 36 beats/min. An ambulance is called and she is taken to the nearest emergency department because of her severe bradycardia. Results of a 12-lead ECG obtained on arrival is shown below:

Questions to consider:

1. What does the ECG show and what is the reason for the abnormality?

2. How do the ECG findings explain the patient’s bradycardia and relative hypotension as assessed by the automatic BP cuff?

3. What further diagnostic testing is warranted?

4. How should the patient be treated?

Answers and Disucssion>>>

1. What does the ECG show and what is the reason for the abnormality?

Answer. The ECG shows sinus rhythm with premature ventricular contractions (PVCs) in a pattern of bigeminy. The PVC morphology is left bundle branch block with a late precordial R wave transition (QS-wave V1 and V2 to R-wave in V3) and inferior axis (positive R waves in II, III, avF) consistent with a right ventricular outflow tract (RVOT) location. Outflow tract PVCs and associated ventricular tachycardia (VT) are among the idiopathic VTs occurring in approximately 10% of patients with ventricular arrhythmias that do not have evidence of structural or ischemic heart disease. As compared to ventricular arrhythmias in patients with ischemic/structural heart disease, idiopathic outflow tract tachycardias have a benign course in most patients. Two important caveats are RVOT ventricular tachycardia that can occur in the context of arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia (ARVD), and patients having a very high PVC burden as discussed below.

Question 2. Answer and Disucssion>>>

2. How do the ECG findings explain the patient’s bradycardia and relative hypotension as assessed by the automatic BP cuff?

Answer. A reading from a manual BP cuff will show hypotension and a pulse deficit due to ineffective ventricular contraction during PVCs with insufficient pressure to allow full opening of the aortic valve. The isolated forceful beats resulting from the increased stroke volume associated with the normal beat following the PVC cause the palpitations that are the most common reported symptom (48% to 80%). Progressive fatigue, however, may be the predominant reported symptom with a high burden of PVCs that results in a reduced cardiac output state. Indeed, patients with a high burden of ventricular ectopic beats can develop a reversible form of left ventricular (LV) systolic dysfunction. A 24-hour PVC burden of greater than 20% is accepted as conferring an attendant high risk for development of PVC-induced cardiomyopathy.

Question 3. Answer and Disucssion>>>

3. What further diagnostic testing is warranted?

Answer. After baseline ECG testing, a 24-hour Holter monitor can determine percentage PVC burden and whether the contractions are monomorphic versus polymorphic. Patients with frequent PVCs should undergo echocardiography and/or stress testing to rule out structural and/or ischemic heart disease. During stress ECG testing, outflow tract (idiopathic) PVCs typically are more pronounced at rest and are suppressed with exercise, whereas ischemic PVCs may be induced with exercise and can persist into recovery. In the case of RVOT PVCs/VT, attention should be focused on the chamber size and systolic function of the right ventricle (RV), which if abnormal would raise concern for ARVD. The diagnosis of ARVD can be confirmed with cardiac MRI, which would reveal fibro-fatty replacement of the RV myocardium. It is a general practice to monitor patients with PVC burden exceeding 5% with annual ambulatory ECG monitors and echocardiograms.

Question 4. Answer and Disucssion>>>

4. How should the patient be treated?

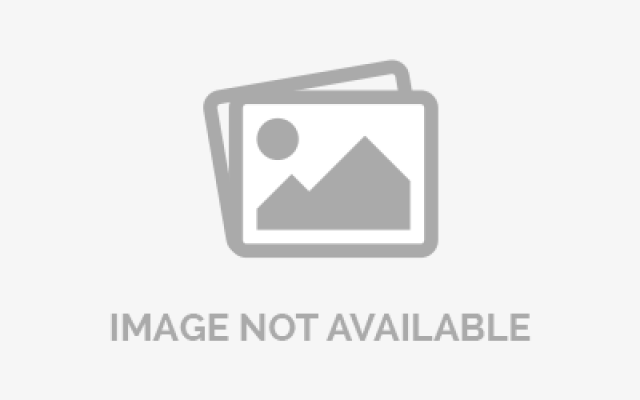

Answer. The treatment of PVCs depends on their underlying etiology, burden, and associated symptoms. PVCs occurring in the setting of ischemic heart disease would be expected to resolve with treatment of underlying coronary artery disease through medical therapy and/or revascularization. With idiopathic PVCs, suppressive treatment is only indicated in the case of symptomatic and/or frequent (greater than 10-20%) PVC burden, and particularly if there is evidence of PVC-induced LV systolic dysfunction. Verapamil and flecainide are pharmacologic options, but may not be tolerated in younger patients with lower resting blood pressure and heart rates and may additionally be ineffective in patients with high PVC burden. An electrophysiology study (EPS) with radiofrequency ablation (RFA) of the RVOT PVC focus is a minimally invasive and potentially curative option that can obviate the need for long-term medical therapy. The procedure involves advancing a mapping electrode catheter via the femoral vein to the endocardial surface of the RVOT. Three-dimension electrical intracardiac anatomic mapping is performed during ongoing PVCs/VT to delineate the exact arrhythmogenic focus, which can then be targeted with catheter radiofrequency ablation (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Detailed 3D electroanatomic activation mapping of the RVOT PVC focus. White central area represents earliest focal PVC activation (left image) for targeted radiofrequency catheter ablation (right image).

Case Conculsion>>>

Conclusion: Results of a 24-hour Holter monitor test in this patient showed a monomorphic RVOT PVC burden of 30%. Stress echocardiography revealed normal RV size and function with borderline global LV systolic dysfunction; PVCs were suppressed with exercise and there were no stress–induced ischemic findings. A trial of verapamil was not tolerated due to hypotension. She therefore underwent successful EPS with catheter ablation. Post-ablation, there has been no evidence of recurrent PVCs either symptomatically or as confirmed with repeat 24-hour Holter monitoring. Additionally, repeat echocardiogram 3 months post-ablation showed normalization of left ventricular systolic function.