Article

Face Transplants: NYU's Ready to Roll

Author(s):

It's been nearly 3 years since Eduardo Rodriguez, MD, performed the most comprehensive face transplant ever done, a procedure that gave a Virginia man a new face, jaws, teeth, and tongue. Now NYU Langone Medical Center's chair of the Department of Plastic Surgery and Director of the Institute of Plastic Surgery and Helen L. Kimmel professor of reconstructive plastic surgery, Rodriguez is poised to do New York's first face transplant. He's just waiting for the phone to ring with news that a donor has been found.

The patient is waiting. The regulatory approvals are set. The multi-disciplinary medical specialists are rehearsed and in place. All they need is the right donor and NYU Langone Medical Center will perform New York’s first face transplant.

“If I get a call, I’ll have to leave right now,” said Eduardo Rodriguez, MD, DDS, chair of the Department of Plastic Surgery and Director of the Institute of Plastic Surgery and Helen L. Kimmel professor of reconstructive plastic surgery, in an interview at NYU last week. He declined to provide details about the patient selected to receive a donor's face.

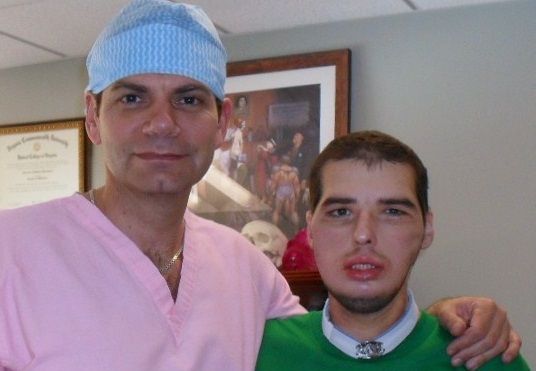

It’s been over 2 years since Rodriguez made global headlines with what he said is the most extensive and complicated face transplant ever done, a 36-hour operation on a Virginia man, Richard Lee Norris, then 37, who at the age of 22 had blown half of his face off with a shotgun. The procedure was done at the University of Maryland in March 2012. Rodriguez joined NYU in November, 2013.

Though the first face transplant was performed in 2005, and there have been about 30 since, the anticipated NYU face transplant will likely be big news. Meanwhile, Rodriguez has more in store, all procedures likely to surprise and even shock the public. Those include doing penis transplants, abdominal wall transplants, and bringing uterine transplants, already done elsewhere, to NYU. As with face transplants, these procedures fall under a regulatory category called vascularized composite allotransplantation.

Dr. Rodriguez also expects to do surgical revisions on some of the other highly publicized face transplant patients whose results left them looking far short of normal. In addition, his expertise in restoring patients’ ability to blink also holds promise, he said.

All are on the near horizon at NYU he said.

The penis transplants are particularly important to the military and Rodriguez gets funding from the US Department of Defense and the Armed Forces Institute of Regenerative Medicine.

“We have a number of male soldiers who require genitalia and would like to have this vital organ,” he said.

In a recent development that should make it easier to find donors, organ allocation authorities have expanded the regional donor pool to cover all of New York State, he said.

To ensure that potential donors and their families have a clear choice, consent procedures allow them to opt out of such tissue donations when they give permission for solid organ donation. He said it is difficult to assess the need for transplants in veterans, but that roughly one soldier out of every 100 who experiences a catastrophic facial injury (about 25% of total battlefield trauma cases) is likely to be a face transplant candidate.

In the Norris case in 2012, though Rodriguez and other surgeons had done several reconstructions on Norris’ face, the results still left him severely disfigured. He avoided going out in public, and when he did he wore a surgical mask and baseball cap so he’d get fewer stares and rude comments. (Pre-op photo at right).

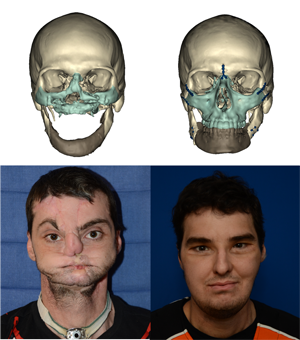

“After a number of procedures we realized the only way he could normalize his appearance and his function was through a comprehensive face transplant,” Rodriguez said. The results were so dramatic, both medically and cosmetically, that Norris was featured on the cover of GQ Magazine, his dark eyes peering out from the donor face that is now his own. The donor, according to news accounts, was a 21-year-old Maryland man who was fatally struck by a minivan as he was crossing a street. That man’s family has met Norris and they keep in touch.

The surgery meant removing not only the donor’s face, but his upper and lower jawbones, his teeth, and his tongue. His solid organs went to other patients. In addition to challenging the team’s skills, the operation was emotionally draining, Rodriguez said. “It is difficult removing someone’s face not knowing if it will work,” he said, “You can imagine the dilemma surgeons go through knowing the possibility we are making the patient worse with the hopes of making him better.”

All went smoothly, “But your heart is racing until you connect the blood vessels, until you see this face that’s pale and cool turn pink and warm, you’re not at ease." Even after the patient is safely in the recovery room, the next hurdle is waiting for the patient’s immune system to try to reject the graft. “That will happen; in this case we had great match and when it happened we were able to use additional medications to treat it,” he said.

Rodriguez said he still gets emotional when he remembers seeing Norris get his first look at his new face. (Norris with Rodgriguez after surgery photo at left.)

As a reconstructive surgeon, he was used to seeing patients with devastating injuries or other anomalies that might horrify a lay person. “I am used to looking in their eyes and when you look in their eyes we know the eyes are the window to the soul; we see them as normal patients, we see their heart and their soul,” he said.

But on seeing Norris’ expression as he looked in the mirror after surgery, and realizing “for him it was as if he was normal self again” Rodriguez had the same reaction as Norris and his family. “For everyone in the room, there was not a dry eye,” he said. (Lancet photo composite at right shows the transformation.)

In the videos below Rodriguez talks about the Norris case, penis transplants, and other plans.