Article

First Person: Parte for a Mother

Author(s):

Can loss make you a better doctor? A psychiatrist reflects on his mother's death.

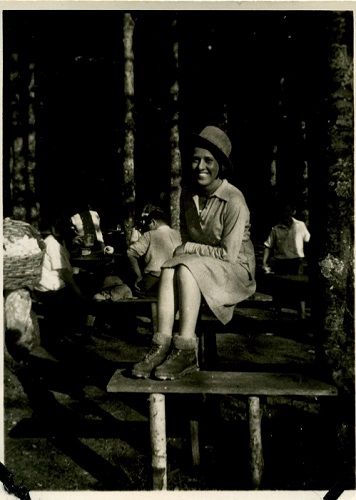

Editor's note: In this first offering of a new MD Magazine feature "First Person", Hans Steiner, MD, professor of Psychiatry and Human Development at Stanford University School of Medicine, reflects on the death of his mother. We hope you'll enjoy his moving remembrance. Submissions welcome at gscott@MDmag.com.

The walk from the church to the grave site was long, leading through rows of tombstones, some tilted, full of cracks and moss, some illegible, some smooth and new. The moist air was rich with the smell of boxwood. A faint smell of burning leaves accompanied the muffled talk and shuffling steps of the 30 people following the casket. A lot I thought, mostly family. That used to be a much bigger group. Many had died as well. There were some who carried grudges right up to this moment. Tante Steffi had not come, resentful because Anny, my mother, beat her to the last spot in the family cemetery plot. Anny would rest forever with Johann, her husband. Steffi would have to look for a spot for herself, eternally separated from Andi, Johann's’ brother who was buried with him. The cemetery’s administration was very strict: only five people to a plot in the central graveyard of Vienna, the Zentralfriedhof.

So it was Anny, Johann, Andi and the brothers’ parents.

The mortuary where Anny’s casket lay in state was filled with flowers, on wreaths, in vases, others just bundled. Bright colors everywhere, all her favorites: lime green, orange, red, white, yellow. Their intense perfume warmed the cold, tiled room. The pallbearers looked professionally sad, anticipatively working on the tip they would receive at the grave site.

When I saw Anny last, she appeared much smaller than I remembered. She had lost a lot of weight. Her upper dentures were missing. Her eyes looked grey and tired, and only fleetingly focused on my face. There was no recognition, even as she looked directly at me. Her hand felt as smooth and warm as it always had. Her voice was barely audible, and the words were random strings of sound.

“She over there has a pillow. I am sure. And always that bicycle. I will eat ham,” she said.

One of her comments always hit me hard, because it made me think she was back, although I knew there was no chance: “Think of me” she said. It was as if she suddenly peeked out from a secret hiding place. An expression flowed over her face that was so familiar, so quintessentially her that it was hard to believe that Anny was not present in some form. "Sag mir..." (Tell me now….) she would start, and as I leaned forward to answer the precious request to tell her something, her eyes drifted out of focus. An invisible force carried her away, back into the recesses of her damaged mind, away from the commerce of this world.

Sister Katharina came into the room. “ Well, Annilein, how are you today?” Turning to me, she asked, “How long will you be here this time?”

“Till tomorrow”.

“Ah. Then back to California?”

“Yes”. Sister’s continuous cheerfulness grated on me. And made me feel guilty.

“Oh well, then you need to enjoy every minute with Anny. Should be easy for you. You are a psychiatrist, right? I know she has been looking forward to seeing you.”

Bloody Hell! She doesn’t recognize or even see me! Why does she say this!

“We have a nice concert this afternoon: Schubert. Will you take Anny downstairs? I am sure she will enjoy it,” Sister Katharina said.

“We will come.”

I barely could get the words out. Why did this woman make me want to strangle her?. Sister’s Catholic presumptuous ways infuriated me, because I as a doctor knew: Anny had been gone for two years. Mutti, my mother, was almost brain dead, gone, forever, not with us, not with me. She was the undead. Every time I saw her sitting tied into this chair, completely vacuous, no trace left of her impish wit, I cringed. How humiliated she would feel if she knew.

I pushed the wheelchair into the cafe, as they called the large room downstairs. The smell of institutional cleaner hung thickly in the air. The room was full of grey heads, most of them women, many asleep, drooling, hanging to the side of their chairs. Some sitting straight up, seemingly alert until they opened their mouths. “I want my picture” one of them proclaimed dolefully, as she held up her tea cup.

The pianist took his place at the keyboard of the Bosendorfer in the middle of the room. Shortly thereafter, the singer, Liliana Szegeti, not more than 30 years old, entered. Her long black dress curved around her body, embracing shoulders, bosom, pelvis, hiding her legs. Her black shiny hair flowed down to her waist. Brushing across the floor like a spring breeze, her easy step hushed the group. Liliana leaned against the piano and began to sing. Her voice, sensuous, evocative, effortless made me want to be thirty again, and Hungarian. “Leise flehen meine Lieder durch die Nacht zu dir…..” she sang, “quietly sending my songs through the night to you. . .”.

Suddenly, Mutti sat up. She did not look over to me, but extended her hand to hold mine. Now as always, I was surprised to find that it had the same feel to it as it always had: soft and warm. The silly patterns of her vitiligo made it look as if she had a pair of defective gloves on. I grasped her hand tightly.

All of a sudden from across the room, one of the grey heads lifted. “Is this a man or a woman singing?” The sentence screeched across the room and above the music. A bubble of laughter came up my throat, irrepressible. How could you mistake Liliana for a man? De profundis, desperate.

In response to the screech, suddenly my mother’s hand moved in the rhythm of the Lied. “Ruehren mit den Silber toenen jedes weiche Herz…..” a soft heart stirs with the silver tones.

Anny was entirely on target with the piece’s rhythm. As I looked over, there still was that drape across her gaze that made it seem she looked straight through me. But if I closed my eyes, we were back at the Vienna Folk Opera, the Volksoper,- me at ten, at my first opera with her, Nabucco. I could smell her perfume, see her carefully coifed hair, touch her silken dress. She was about 45. I remembered. This was her way of showing me a world of beauty and powerful emotion: Jews in pharaoh’s clasp longing for freedom. There was a lasting message for me.

Throughout the afternoon, Mutti directed the songs, holding on tight. She did not miss a beat, until Sister Katharina came and said it was time for a pureed dinner.

Before I could leave, I had to go to the garden. It was one of those Vienna golden autumn afternoons, sunlight playing on red leaves and yellow buildings--the air still warm, but edged with sharpness. Winter was not far away. I sat in the farthest corner, face in my hands, my shirt wet. Maybe Sister was right. Maybe. But if she was, how about that flight tomorrow? So precious little time left. So little of Anny left.

It was to be the last time I saw her alive. The notification of her death came during a talk I gave in Regensburg. The gold of fall had turned into the icy grey of early winter. I was again on my way to Vienna to visit Mutti, but this time, I only could bury her.

Anny died of a midbrain stroke in the night of the 20th of September, 2005. The stroke was not preventable. It could not be treated. She had a large kidney stone which destroyed her right kidney. Because of her frailty and age, she could not be operated on without risking death from the operation. The dying kidney periodically would release vaso-constrictors causing hypertensive crises. These could not be controlled, because she was at the upper limit of receiving medications and increasing her dose would have likely brought on a hemorrhagic stroke, which also would have killed her. She had suffered three similar strokes before, all destroying increasing amounts of her brain tissue, leading to her dementia. She recovered — somewhat miraculously – from these three previous strokes, but lost more and more of herself with each one of them. She was not aware of her losses; she did not suffer any pain as she died.

Doctors seem to use a reverse telescopic lens to look at illness and death, rendering them distant foes, a mere matter of pathophysiology. We excel at calmly looking at facts in the most dire situations, explaining events, calming families. We are realists, even hyperrealists. Sometimes, that is not enough: we too need solace.

Then it is better to think that Mother Nature called Anny home to rest; that she was kind: she gave Anny and me Liliana and Franz Schubert as messengers to saying good bye when other channels were forever closed. That last concert gave me a story to write. I was there for Mutti’s final moments. Being fully present, I reached depths that hurt a lot. Writing about that last visit makes these moments unforgettable. Yet it has another paradoxical effect: it revives me, gets me ready to do my job, to listen, to soothe suffering in others and to heal.

Dr. Steiner directs The Pegasus Physician Writers, a group at Stanford.