Article

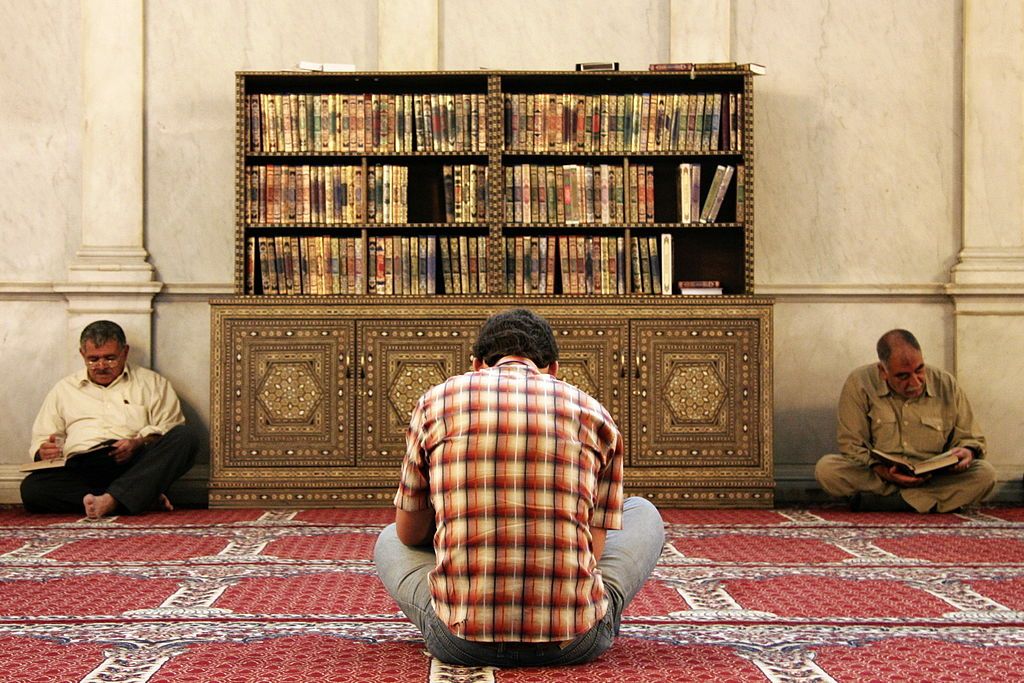

How Does Ramadan Fasting Affect Diabetic Muslims?

Author(s):

More research and education could to prevent inherent risks

Physicians need to look more closely at the effects Ramadan fasting has on diabetic Muslims, according to Osama Hamdy, MD, Director of the Inpatient Diabetes Program at Joslin Diabetes Center.

Hamdy, who presented his position at the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists’ (AACE) annual meeting in Austin, TX on Thursday, noted that cultural considerations are part and parcel of optimal diabetes care around the world, and Muslims who fast during Ramadan are a special group whose disease management requires special attention.

Nearly 95% of Muslims who have diabetes fasted for at least half of the month during Ramadan, and 66% fasted every day, Hamdy said. Summer fasting periods can last up to 20 hours per day and are often undertaken in hot and humid conditions, which can further exacerbate fasting-associated risks like hypoglycemia, hyperglycemia, dehydration and thrombosis, and diabetic ketoacidosis.

Few patients with type 2 diabetes who used insulin could safely fast during Ramadan, Hamdy added. They would need to adjust their insulin doses and timings to allow for a greater number of fasting days without acute complications.

Further, Hamdy emphasized that Pre-Ramadan diabetes education is necessary to avoid complications in those who insist on fasting. This education should focus on six key areas: risk quantification, blood glucose monitoring, fluids and dietary advice, exercise advice, adjusting treatment regimens, and when to break the fast.

In a study that monitored the change in thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) before and after Ramadan in patients with primary hypothyroidism, researchers led by Aisha Sheikh found that 62% of patients had changes greater than or equal to 2 mu/l of serum TSH by the end of the Ramadan fasting period.

The study also monitored the impact on TSH with regards to the quality of meals and intervals between meals and levothyroxine — a treatment for thyroid hormone deficiency.

During the study period, 64 patients with hypothyroidism were enrolled, with 58 females and 8 males aged between 22 and 70 years with a mean age of 44.2 +/- 13.2 years. The mean difference in TSH pre- and post-Ramadan was 2.32 +/- 3.80 mIU. However, the difference in TSH was not significant between those who were compliant with meals and levothyroxine and those who were not.

“Changes in TSH concentrations during Islamic fasting in the month of Ramadan are statistically significant, but these changes are clinically less important,” the study read. The more meaningful finding was that “changes in TSH due to Ramadan are not affected by the timing of thyroxine intake and intervals from meals.”

The time frame for Ramadan fasting, which includes no foods or fluids, begins at sunrise following Suhūr, the meal consumed pre-dawn, and concludes at sunset with Iftar, the meal served at the end of the day. This year, Ramadan in the US begins the evening of Friday, May 26 and ends the evening of Sunday, June 25.

Read Sheik’s study, The Impact of Ramadan Fasting on Thyroid Status in Patients with Primary Hypothyroidism.

Read the AACE list of press releases.