Article

Injecting Botulinum Toxin into Epicardial Fat Pads Reduces Long-Term Post-Op Atrial Fibrillation Risk

Author(s):

Results from a small trial suggest that injections of botulinum toxin, administered after bypass surgery into the fat pads that surround the heart, may reduce the danger of postoperative atrial fibrillation (AF) and virtually eliminate the danger of recurrent AF.

Results from a small trial suggest that injections of botulinum toxin, administered after bypass surgery into the fat pads that surround the heart, may reduce the danger of postoperative atrial fibrillation (AF) and virtually eliminate the danger of recurrent AF.

The findings of the study, which were announced at the Heart Rhythm Society’s 2015 annual meeting in Boston, promise to reduce the long-term risk associated with such procedures and hint that similar injections just might prevent AF in a far wider variety of cases.

As part of the randomized double-blind study, 30 patients with a history of paroxysmal AF received 1 ml injections of botulinum toxin immediately after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Another 30 patients received the placebo treatment, 1 ml injections of saline solution. The study team then used implantable loop recorders to assess each patient’s sinus rhythm for a full year after surgery.

Just 2 of 30 patients who received botulinum toxin (7%) — compared to 9 of 30 in the placebo group (30%) — experienced postoperative AF in the 30 days after surgery (P=0.024).

The apparent benefit of the treatment was even greater between the end of the first month and the end of the first year. During that time, 7 of the 30 patients in the placebo group (27%) and none of the 30 patients in the botulinum toxin group (0%) had recurrent AF (P=0.002).

Over the entire 12-month period, the mean AF burden, as measured by the implantable loop recorders, was significantly reduced by botulinum toxin compared to placebo, 0.07±0.1% vs. 1.5±0.6%, respectively (p<0.001).

The international team of researchers that performed the study noted that patients in the study and control groups were very well matched and that surgeons had successfully injected every epicardial fat pad in every patient with no complications.

Team members also said that the injections added relatively little time to the procedure — 11 minutes on average ± 6 minutes — before concluding that the technique merits further study.

“Botulinum toxin injection into epicardial fat pads during coronary artery bypass graft provided substantial atrial tachyarrhythmia suppression both early as well as during 1-year of follow-up, without any serious adverse events,” they wrote.

The US Food and Drug Administration first approved botulinum toxin in 1989 for the treatment of vision problems, but the versatile substance has since received indications for 8 medical conditions and become best known as a wrinkle treatment.

The idea of injecting it into epicardial fat pads, with the goal of disrupting the fat’s production of hormones and cytokines and possibly preventing AF, was first tested (successfully) in animals.

The human trial made news before it even began, and the announcement of the results generated a stir at the meeting in Boston.

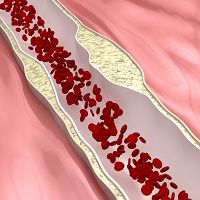

Postoperative AF develops in 30% to 40% of all patients who undergo bypass surgery, and there are, at present, no commonly used techniques to reduce that risk. The risk of recurrent AF, on the other hand, can be managed to some degree, but any improvements to current prevention techniques could certainly save many lives, and the results of the new study indicate that botulinum toxin might constitute a real improvement with surprisingly long-lasting results.

The effect of Botox on facial wrinkles is notoriously short-lived but the 1-year results from the new study indicate that it is more durable in epicardial fat.