Article

Lead Danger Doesn't Stop at City Limits

Author(s):

Not worried about lead in your water? You should be, says Newark toxicologist Steven Marcus, MD.

Suburbanites may think there is not much chance there is is lead in the water they drink.

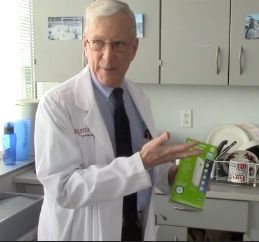

That’s probably because they haven’t talked to Steven Marcus, MD, a Newark, NJ toxicologist (photo) who has spent much of his career worrying about lead.

Marcus is a professor of emergency medicine and associate professor of pediatrics at the New Jersey Medical School of Rutgers University, based in Newark. He is also the medical director of the medical school’s New Jersey Poison Information and Education System.

"Newark as an older city may have a little bit bigger problem,” he said, "but you could move into a new house right now and have it be contaminated—the faucets in your house were probably manufactured with brass inside them and brass can be contaminated with lead.”

Lead in water at any level is toxic. It stunts brain growth, and lowers intelligence potential.

Lead contamination is a major threat to drinking water in older cities with aging pipes in homes and buildings.

The federal government has taken steps to protect the public.Lead pipes were outlawed for new construction in 1986 and soon after that the Environmental Protection Agency began requiring municipal water supplies to be tested for lead.

Marcus says that despite those measures, even new houses are likely to have lead in the water from untested faucets, solder, or pipes that bring lead-free water from a municipal water source but contaminate the water en route.

The US is far from alone, he added.

“This is a societal problem across the country, probably across the world, and it has been little understood and really not addressed until the Flint, Michigan thing,” Marcus said.

[Marcus discusses lead in two video interviews here and here.]

The lead problem in Flint, MI surfaced in 2014 after that city had a major problem with brown, corrosive water coming into homes through the municipal water supply, drawn from the Flint River.

Officials then started testing water and found yet another problem: high lead levels.

“To be honest, lead was the minor problem in Flint,” Marcus said, “People were complaining that their skin burned from the water, they were losing their hair—that doesn’t happen with lead.”

Still, in Flint the lead contamination was pervasive.

The EPA permits 15 parts per billion. In Flint, testing of homes levels as high as 13,000 ppb. Overall the level for Flint was 27 ppb.

The city of Newark has known since at least 2004 that there was lead in some of its schools’ drinking water. This year officials discovered that 30 of its schools have dangerously high levels of lead in their water. In Newark, the lead levels in water coming out of the schools’ taps were mostly below 100 ppb but some were as high as 558 ppb.

There is no federal law requiring schools to do lead tests, just the EPA mandate requiring testing of water supplies at the source.

School officials in Camden, NJ, the state’s poorest city, also have known for more than a decade that their drinking water is contaminated and switched to bottled water due to the expense of redoing the pipes.

More recently, New Jersey’s governor announced the state would test all its public schools’ water for lead, beginning with the 2016-2017 school year. Several districts have decided not to wait, and their findings of high lead levels have made local headlines.

The danger is likely far more pervasive than lead in water in schools, Marcus said.

The problem is that even if water is lead-free when it leaves the water supply facility, as it travels through pipes it can pick up dangerous heavy metals like lead and copper.

Even if their household water is safe consumers are at risk in ordering a beverage in a restaurant, drinking a bottled one, or even using a filtering device that has not been tested and certified by the National Science Foundation.

Bottled water is safer, but comes with its own environmental concerns, such as the environmental toll in shipping bottled water globally.

To protect himself and his own family, friends, and colleagues, Marcus has water filters installed at home and in his workplace (photo at right), and takes a portable pitcher-sized filter on vacation. (There are several NSF-certified pitcher brands available for about $40, plus the cost of replacement filters.)

Before he drinks a beverage at a restaurant he’ll ask whether the water is filtered.

He believes that even the existing federal standards for allowable lead in drinking water are not adequate to protect the public.

"We've got to stop using kids as lead detectors," he said, inspecting homes or testing water only after a child has lead poisoning.

The EPA standard for lead in drinking water should be stricter, he said.

In Europe the lead standard is 10 ppb, and Marcus would like to see it drop at least to 5 ppb, preferably to zero.

But until very recently, Marcus added, it has been hard to get anyone to pay attention.

“I feel like I’m constantly an ‘Enemy of the People’,” he said, referring to Henrik Ibsen’s classic play about a physician who cannot get his town to do anything about its contaminated municipal baths. “My career is full of episodes where I’ve picked up a problem and nobody would listen to me until they were hit over the head with a hammer.”

Editor's Note: For a profile of the Flint, MI physician who brought the lead problems to the public's attention, go here.