Article

The Location of Broken Bones Predicts Life Expectancy in Elderly Patients

Author(s):

The location of a broken bone can significantly impact the long-term health outcomes of older individuals, according to the new research findings to be presented at the Endocrine Society (ENDO) 2020 Annual Scientific Sessions.

praisaeng@AdobeStock_95334607

The article "Fracture Location Related to Increased Mortality," was originally published in HCPLive.

The location of a broken bone can significantly impact the long-term health outcomes of older individuals, according to the new research findings to be presented at the Endocrine Society (ENDO) 2020 Annual Scientific Sessions.

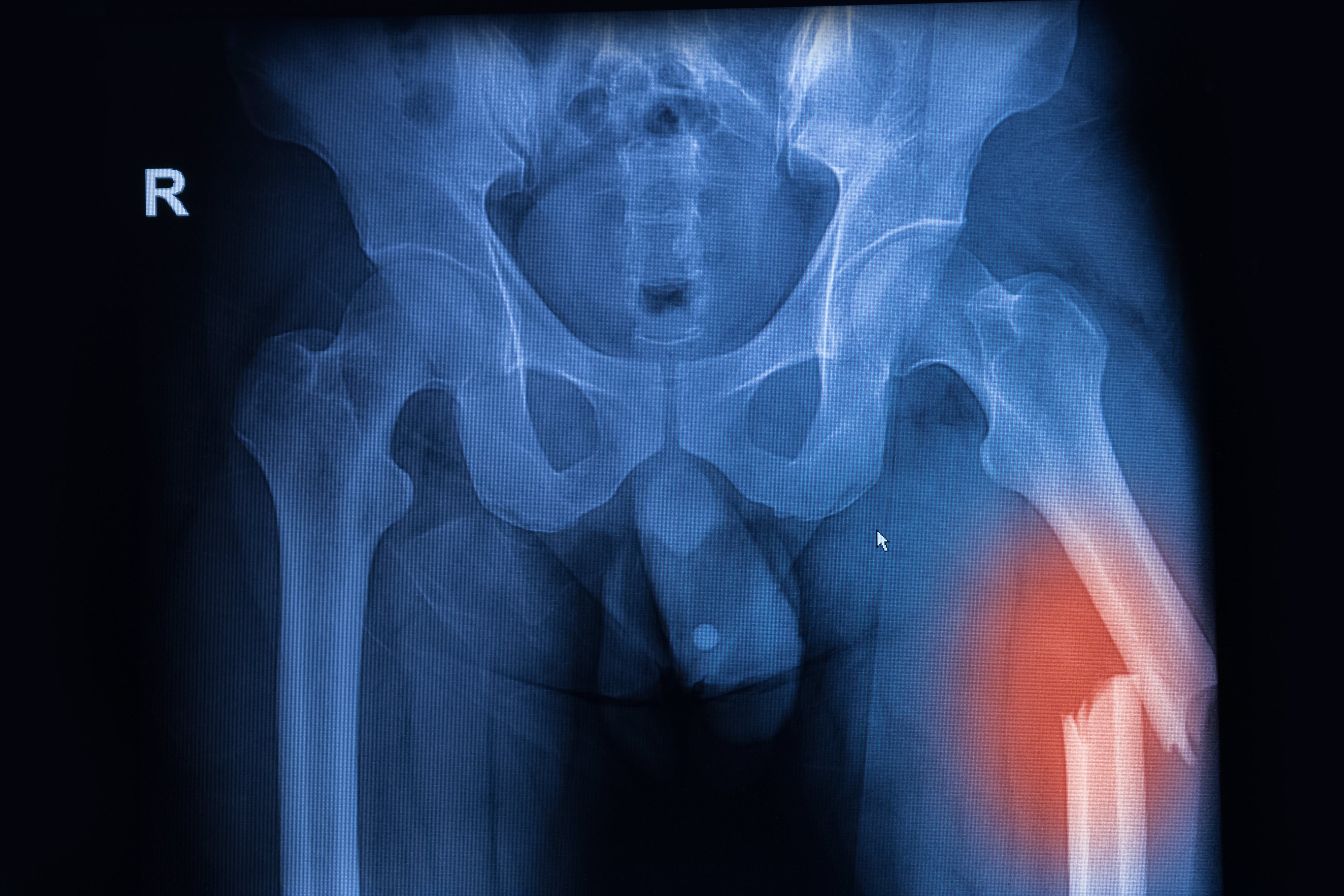

Jacqueline Center, MBBS, FRACP, PhD, and a team of investigators found that older people who had broken bones closer to the center of the body (proximal fractures), such as upper arm or leg, pelvis, and ribs, had a greater risk of being admitted to the hospital for major medical conditions. Such patients also faced a greater risk of dying prematurely following their fracture compared to similarly aged patients without fractures.

The findings highlighted the importance of treating patients for their bone health, Center, from the Garvan Institute of Medical Research in Australia, said in a statement.

“We now have information allowing us to understand why people do badly after a fracture and how we may intervene to improve outcomes,” she added.

Center and her team studied 300,000 patients >50 years old with a low-trauma fracture from the Danish National Database between 2001-2014 The team looked at differences in the reasons for hospital admissions following the fracture and patterns of death between patients with proximal fractures and those with fractures further away from the center of the body (distal)-wrist, ankle, hand, or foot.

The investigators matched people with fractures to those without fracture 1:4 by sex, age, and comorbidity status.

Overall, the team included 212,498 women and 95,372 men with fracture. There were 30,677 (women) and 19,519 (men) deaths over 163,482 and 384,995 person-years of follow up, respectively. Mean age at fracture was 72±11 for women and 75±11 for men. A majority of the patients (75% of men, 60% of women) had >1 comorbidity. Each additional comorbidity led to an increased risk of mortality for all fracture types, but only for proximal did the fracture alone increase mortality risk over comorbidities.

Proximal fractures included hip; femur; pelvis; rib; clavicle; and humerus and had increased mortality compared to those without fractures.

Patients with broken bones at proximal locations had a 1.5- to four-fold greater risk of death over the next 2 years than patients without fractures. The patients with proximal fracturs were also more likely to be admitted to the hospital for cardiovascular disease; cancer; stroke; diabetes; pneumonia; and lung disease.

Mortality risk at 2 years follow-up was increased for proximal fractures regardless of whether they were admitted to the hospital after the injury. Those with distal fractures had similar or lower death risk and similar admission patterns as patients without fractures.

The findings provided insights to why patients with proximal fractures die prematurely, Center concluded.

Additional research should focus on ways to prevent premature deaths related to fractures.

The study, “Understanding Why Older People with Low Trauma Fractures Die Prematurely,” will be presented at the Endocrine Society (ENDO) 2020 Annual Scientific Sessions.”