Article

Managing Chronic Cirrhosis After Progression to Liver Failure, Gastrointestinal Bleeding

Author(s):

In his presentation, George Therapondos, MD, a hepatologist at the Ochsner Medical Center, detailed how to manage inpatients with cirrhosis that progresses to liver failure and gastrointestinal bleeding.

In his presentation at the 14th Annual Southern Hospital Medicine Conference, held November 7-9, 2013, in New Orleans, George Therapondos, MD, a hepatologist at the Ochsner Medical Center, discussed how to manage inpatients with cirrhosis who progress to liver failure and gastrointestinal bleeding.

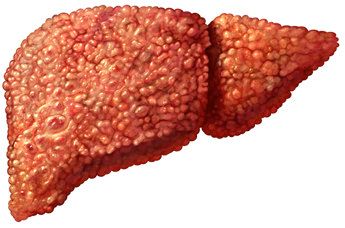

Therapondos began by reviewing the causes of chronic cirrhosis, which include alcohol, viral hepatitis, fatty liver, autoimmune disease, hemochromatosis, and vascular and idiopathic disease, as well as the causes of acute liver failure, which comprise of drug toxicity, viruses, toxins, vascular and idiopathic conditions.

Cirrhosis is the point when repeated damage and accumulated scarring becomes irreversible. The condition then progresses to advanced cirrhosis, followed by end-stage liver disease, advanced liver disease, and, finally, decompensated cirrhosis, or liver failure. According to Therapondos, the overall 5-year survival rate for liver failure is only 50%.

Common complications in liver failure include gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding from esophageal and gastric varices, ascites, renal dysfunction with low sodium, high creatinine, and hepatorenal syndrome. Additional complications consist of hepatic encephalopathy, hepatocellular carcinoma, and hepatopulmonary syndrome and portopulmonary hypertension ascites, Therapondos said.

The treatment of acute GI bleeding secondary to liver failure consists of supportive care and airway protection, especially in patients with impaired consciousness. Other treatment approaches include blood transfusion, correction of clotting and platelet abnormalities, endoscopy and banding, octreotide to reduce portal hypertension, esophageal tamponade with balloon, and transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) surgery. Therapondos also stressed that antibiotics must be used prophylactically, as the strategy has been shown to reduce infections by 32% and mortality by 9%.

Therapondos said recurrent GI bleeding in liver failure is common because the gastric varices increase progressively in diameter and may rupture. Primary prophylaxis of bleeding is intended to prevent the first bleed by using beta blockers or endoscopic variceal band ligation (EVL). Though small varices may not require treatment, medium or large varices should be treated with beta blockers first, and EVL should be used an alternate therapy.

Secondary prophylaxis is intended to prevent re-bleeding, which Therapondos said is also common in liver failure. EVL and beta-blockers should be used, though TIPS is considered to be rescue therapy, as it can precipitate cardiac failure and may lead to further decompensation and death.

Therapondos said gastric varices are typically treated with octreotide, Histoacryl or Dermabond injections, and/or TIPS. Portal hypertensive gastropathy usually affects the proximal stomach and responds to reduction in portal pressure. Gastric antral vascular ectasias are treated with argon plasma in a thermal procedure, beta blockers, and/or TIPS.

Ascites formation results from renal arterial vasoconstriction that causes retention of sodium and water. If the condition persists, hepatorenal syndrome develops, which can result in refractory ascites with either acute renal failure or stable renal failure. Treatment of ascites is intended to maintain an ascites-free state, prevent infection in the ascitic fluid, and prevent hepatorenal failure. Therapondos said the stepwise approach in ascites management consists of dietary sodium restriction, diuretic therapy, paracentesis, TIPS, and liver transplantation — the latter of which should be considered when ascites develops, since the 5-year survival rate after ascites formation is only 20%.

Hepatorenal syndrome treatment usually involves using vasopressin analogues or alpha-adrenergic agonists like norepinephrine and midodrine. Hepatic encephalopathy (HE) occurs in 30 to 45% of cirrhosis patients, and symptoms reflecting a spectrum of neurocognitive impairment may be permanent. Therapondos said treatment includes correcting electrolyte imbalances, treating GI bleeding, and providing supportive care of unconscious patients.

Summarizing his points, Therapondos stated that portal hypertensive bleeding complications are relatively easily managed, ascites and edema are the first steps towards renal impairment and multi-organ failure, and liver transplantation is the only definitive treatment for advanced liver failure.