Article

Managing obesity in patients who have knee osteoarthritis

Obesity is a modifiable risk factor for knee osteoarthritis (OA). Weight loss may reduce the risk of knee OA, and increased levels of physical activity may result in improvements in disability-related outcomes. However, intensity of physical activity is not as important in weight loss as total energy expended.

Increased physical activity and weight loss are central to improving the health care of obese patients who have knee osteoarthritis (OA). Obesity is a modifiable risk factor for the development of knee OA, specifically bilateral knee OA.1,2 Statistically significant relationships have been found between even small increases in body mass index (BMI) and the prevalence of this disease.3 In addition, being overweight or obese has been shown to exacerbate the pain and disability associated with knee OA.2 It follows, then, that managing obesity effectively is important to all physicians caring for patients who are either at risk for or faced with knee OA.

Still, only 46.4% of recently surveyed obese adults who had arthritis were told to lose weight by their doctor.3 Those who did receive this advice were 3 times more likely to engage in a weight loss effort than their peers who were not advised. This demonstrates the importance of the physician's role in overweight patients' attempts to lose weight to manage the pain and disability that accompany this disease: physicians may use a variety of resources to evaluate obese patients and promote needed lifestyle changes.

In this article, we provide an overview of the use of physical activity and weight loss in the treatment of patients who are obese and have knee OA. We also offer practical recommendations on a stepped-care approach to disease management.

The role of physical activity and weight loss

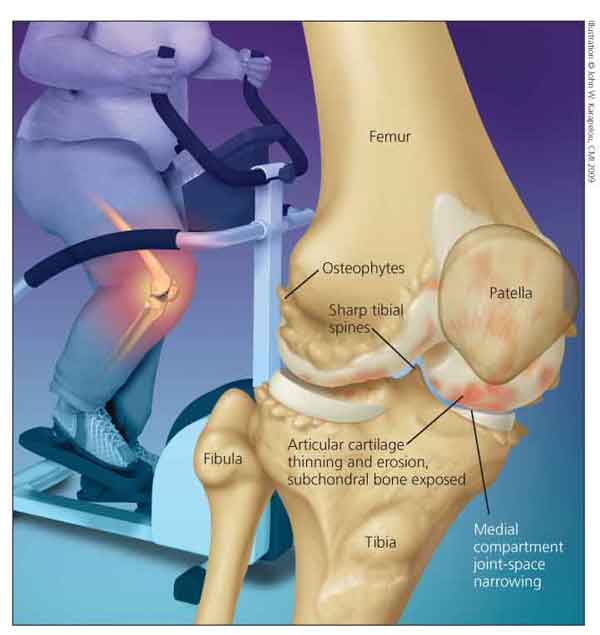

In the absence of a cure for OA, current clinical treatment focuses on interventions to improve patients' functional health and quality of life. Weight loss has been shown to reduce the risk of knee OA significantly4 and is modestly effective in managing the adverse symptoms that accompany disease progres

sion (Figure).

Figure – Weight loss has been shown to reduce the risk of knee osteoarthritis (OA) and may help manage the adverse symptoms that accompany disease progression. Common features of knee OA include osteophytes, medial compartment joint-space narrowing, and sharp tibial spines.

In several randomized controlled trials of patients with knee OA, increased levels of physical activity were found to result in modest but significant improvements in disability-related outcomes, specifically pain and health-related quality of life.5 In addition, physical activity is a critical component of effective weight loss, partly because more calories are burned with increased physical activity. It also may help strengthen the muscles around the knee, thus offering stability during ambulation and transfer from one location to another.

Changes in lifestyle-including increased levels of physical activity and a reduction in caloric consumption that leads to a reduction of weight-are now acknowledged as important in the management of knee OA.6 Evidence from randomized controlled trials supports this position.7,8

Messier and colleagues7 demonstrated that older patients with knee OA who undergo a combined exercise and dietary intervention experience a greater amount of weight loss and superior improvements in physical function and pain symptoms than patients who receive exercise or dietary interventions alone. The combination of exercise and diet resulted in an average weight loss of about 6% of body weight at the 18-month follow-up.

Miller and associates9 examined the effects of a more intensive weight loss intervention in a sample of 87 obese older adults with knee OA. The exercise and dietary intervention yielded a weight loss of 10% of body weight and resulted in significant improvements in physical function and pain symptoms in these patients compared with a weight-stable comparison group.

Collectively, these findings suggest that even a modest amount of weight loss achieved through the lifestyle modifications of exercise and dietary behaviors can result in meaningful improvements in physical function and quality of life for patients with knee OA. Achieving greater amounts of weight loss through appropriate exercise and dietary changes could result in even greater benefits; this currently is the subject of considerable research interest.

Knowledge about the most appropriate types and amounts of physical activity in patients with knee OA is surprisingly limited. To date, results of fewer than 20 randomized controlled trials have been published on this subject.5 Most of these studies focused exclusively on strength training. Muscle loss and weakness in the lower extremities contribute to the pain and functional limitations observed in knee OA. However, there is clear evidence that the most effective physical activity intervention involves both moderately intense aerobic activity (eg, walking) and strength training that targets mostly muscles in the lower extremities.5

Although patients who are obese and have knee OA should be encouraged to engage in both aerobic activity and strengthening exercises, the amount of physical activity prescribed for these patients warrants careful consideration. Often, it is assumed that larger amounts of physical activity will result in more favorable changes in relevant outcomes.

However, evidence from the Fitness Arthritis and Seniors Trial (FAST) suggests that this conclusion should be looked at with caution.10 The FAST participants who were the most active (a mean walking time of about 40 minutes) exhibited pain symptoms and disability at the end of the study that were similar to those of participants in the healthy-lifestyle control group. Patients who completed a moderate amount of aerobic activity per session (about 35 minutes) showed more improvements in pain and disability than did those in the control group. Many of the patients who walked for 35 minutes did so by walking for 15 minutes, resting for a few minutes, and then walking for another 15 or 20 minutes. These findings suggest that prescribing moderate amounts of physical activity, in multiple short sessions, is more likely to elicit improvements in pain and function than training that is excessive in duration.

In weight loss, intensity of physical activity is not as important as total energy expended. Therefore, a reasonable approach is to start patients walking 15 minutes a day 4 or 5 times each week and gradually introduce multiple sessions that result in 30 to 40 minutes a day of moderately intense walking. On a 10-point scale (0 = no effort, 10 = maximal effort), patients should be instructed to walk at an intensity level of about a 5 or 6.

We would also recommend that patients perform strengthening exercises for the lower extremities 2 or 3 days each week.11 A typical session might last 20 minutes and include exercises outlined by Baker and colleagues.12 The exercises, which may be performed 8 to 15 times and repeated twice during a typical training session, include the following:

•Stand at the bottom of a flight of stairs and, using an alternating step pattern, step up and down on the first step.

•Stand about 14 inches away from a wall and, using the hands for balance, rise up and down on the toes.

•Place a pillow on a chair and, with the hands crossed in front of the body, lower the buttocks until they just touch the pillow, hold for a count of 2, and return to a standing position.

•Starting with a light weight (about 3 lb) strapped to each ankle, sit in a chair and alternate lifting the lower segment of each leg until it is parallel to the floor.

O'Reilly and Doherty11 have suggested that rubber exercise bands may be used as an inexpensive and easy-to-use at-home strength-training tool. If exercise bands are to be used, however, we would recommend that they be used in conjunction with the exercises mentioned above rather than replace them.

An efficient way to perform aerobic and strength-training activities is to combine them in one session. Patients may begin by walking for a 15-minute warm-up, then perform the strength-training exercises, then walk for another 15 minutes, and then finish with a 5-minute cool-down walk and stretching.

Recognizing the benefits

The pathology and symptoms that accompany the progression of knee OA present unique challenges in promoting lifestyle behavior changes, especially in obese patients. Often, pain and fatigue of the knee and beliefs related to pain and function serve as barriers that undermine the patient's motivation to adopt and maintain changes in physical activity and dietary behavior. In fact, a growing body of evidence suggests that improvements in pain, increased confidence in patients' ability to perform activities of daily living, and increased satisfaction with function may mediate the effects that lifestyle modification interventions have on the primary functional health and quality-of-life outcomes targeted in clinical practice.

For example, we have found that patients' participation in walking programs improves performance-based measures of physical function because of reductions in pain and improved confidence in the ability to climb stairs and perform other mobility-related tasks.13,14 In the Arthritis, Diet, and Activity Promotion Trial, we found that reduction in pain and improvement in satisfaction with function were the driving forces behind the improvements in health-related quality of life that accompanied the combined dietary weight loss and physical activity intervention.8

Collectively, these results suggest that pain, confidence in patients' ability to perform mobility-related activities, and satisfaction with function are important considerations in treating obese patients who have knee OA. Incorporating basic assessments of these outcomes into clinical practice could provide valuable insight into the health status of a patient and enable physicians to evaluate interventions that they might use with specific patients.

For example, during a routine visit, a physician might ask a patient to rate the intensity of his or her knee pain experienced during various activities that require mobility (eg, walking 1/4 mile and climbing stairs) on a 5-point scale (0 = no pain, 5 = very severe pain), satisfaction with his ability to perform these daily activities (also on a 5-point scale: 0 = not at all satisfied, 5 = very satisfied), and how certain he is that he can perform these activities (on a 10-point scale: 0 = not at all confident, 10 = completely confident). Nevitt2 suggested use of the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index (WOMAC), an arthritis-specific instrument that measures both pain and activity restrictions. Measures of satisfaction and confidence easily could be added to the existing WOMAC inventory.

Making these basic assessments seems prudent given the importance of these outcomes in the management of knee OA and in determining the effectiveness of medical interventions. In addition, these data could be used as a point of connection to keep patients on track with home-based programs.15

Selecting a management plan

Despite the growing acceptance of obesity management in patients with knee OA, little guidance for primary care physicians is available. Wadden and Osei16 provided a stepped-care approach to treatment that is based on the severity of a patient's weight problem, the patient's motivation, and existing risk factors for chronic disease. In a minor modification of this approach for patients with knee OA, we recommend classifying patients by their BMI (calculated by dividing weight in kilograms by height in meters2) in 1 of 4 groups (Table).

Treatment decisions also are based on an individual patient's degree of readiness and need to initiate weight loss. Particular consideration is given to the presence of other risk factors, previous attempts to reduce weight, and patient preferences.

For level 1 patients, the initial approach (step 1) should involve a self-directed program of healthful eating and increased physical activity in conjunction with physician counseling. Physicians should provide regular assessment and feedback on both weight and BMI and provide a supportive environment in which patients can discuss their concerns and frustrations about lifestyle changes. Although modest weight loss may help patients in this level, perhaps a more important goal is preventing weight gain.

Community resources are readily available in most areas of the country to assist patients in their self-directed weight loss efforts. Physicians may make a resource guide available to patients. Guides should include a list of local registered dietitians and fitness facilities; medically sound commercial programs; public health department contact information; and Web addresses for the CDC, American Dietetic Association, and NIH. Or, patients may use an 800 number (800-366-1655) to locate dietitians in their area.

We also suggest that physicians introduce patients to http://www.mypyramid.gov, a US Department of Agriculture Web site that assists in dietary planning. Patients can easily view the approximately 3-minute tour of the food pyramid and enter their basic demographic information while they wait to meet with their physician. In just a few minutes, they are provided with a tool that outlines the healthful foods they need to consume and how much, as well as tips for easy consumption. A summary of this information and meal tracker are available in a PDF format; it can be printed and sent home with patients. In addition, visiting http://www.mypyramidtracker.gov allows users to enter details about their diet and activities and produces an analysis their of food intake and needed physical activity, as well as an "Energy Balance Summary."

Patients in level 1 who have tried many times to lose weight on their own and have not succeeded or do not feel confident in their ability to lose weight on their own may benefit from the more intensive treatment options identified in the second step of a stepped-care approach. This step is most appropriate for patients in level 2; it includes the self-help programs in step 1 but often relies on more structured treatment programs that are led by trained personnel.

For example, level 2 participants who adhered to structured behavioral self-help programs, such as Take-Off Pounds Sensibly, lost 17.9 kg (39.4 lb) after 2 years of treatment and maintained a weight loss of 15.7 kg (34.5 lb) after 5 years.17 Weight Watchers, a commercial program that combines behavior modification and group support with diet and increased physical activity, evaluated the effectiveness of its program; in a randomized trial, patients achieved a 6% weight loss after 6 months.18

A third option in this structured self-help category is the traditional group-based behavioral intervention located at many hospitals and universities. These interventions have been shown to produce a weight loss of 8% to 10% during 6 months of weekly group treatment on a consistent basis.16,19 This approach involves group-based sessions designed to help overweight or obese persons learn how to self-regulate their dietary and activity habits successfully. Patients are provided with homework assignments designed to modify common physical activity, eating, and thinking habits. Weekly group meetings facilitate behavior change by reviewing homework assignments and by helping group participants develop solutions to overcome the barriers.

Using group-based treatment is cost-effective, and the support provided by group members may help produce more weight loss than self-help programs or programs that rely on individual counseling. If such services are not available in the local community, physicians can refer patients to Brownell's 16-week LEARN program for weight loss, described in a manual that addresses behavioral therapy topics in a simple user-friendly manner.20

If patients are unsuccessful in these programs or if they are in level 3, they should be triaged to step 3. This step requires implementing a portion-controlled, low-calorie diet (LCD).16 LCDs involve a daily caloric intake of 1000 to 1500 kcal for women and 1500 to 1800 kcal for men.

This low caloric intake is achieved through the use of liquid or other meal replacements and structured meal plans. Often, structured meals are based on prepackaged frozen food with the addition of fresh fruits and vegetables. LCDs that use structured meal plans and liquid meal replacements have been shown to induce greater weight loss than self-selected diets that use the same caloric intake.19 However, such programs require the services of a registered dietitian and, possibly, the use of prepackaged meals.

Patients' expectations about treatment outcomes are a critical consideration in applying the stepped-care approach. For example, modest amounts of weight loss (eg, 5% to 10% of total body weight) have been shown to result in a significant reduction in the risk of disability as well as in improvements in physical function and quality of life. Felson and colleagues21 found that a weight loss of 2 units of body mass during the middle to late years of life reduced a woman's chances of knee OA by more than 50%.

However, many overweight and obese patients enter treatment expecting to lose up to 3 or 4 times this amount of body weight.22 Not attaining this magnitude of weight change may undermine their motivation to continue treatment. Therefore, it is particularly important that physicians attempt to shape realistic expectations by informing patients of the amount of weight loss that has been shown to be effective in enhancing OA outcomes.

Perri and associates23 offered a convincing argument for the position that the management of obesity is best conceptualized as a continuous care, problem-solving process. In other words, obesity is a chronic health problem that requires lifelong assistance from health care providers.

Patients in level 4 or those in level 3 who have 2 or more risk factors for cardiovascular disease warrant special consideration. These patients are at increased risk for health complications, which often include psychological dysfunction (eg, depression).

When the weight loss efforts described in step 3 are not successful in these patients, bariatric surgery-including gastric bypass and laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding procedures-is the treatment of choice.24

Gastric partitioning induces an initial weight loss of 25% to 30%. However, in presenting this treatment option, physicians should inform patients of the risks, which include a 0.5% to 1% mortality rate. In addition, patients who are medically eligible for the surgery must also recognize that it will radically change the types and amounts of food they will be able to consume postoperatively. Accordingly, patients must be informed and acknowledge that long-term modification of eating and activity habits is an essential part of the success of this treatment option.

Pain and functional decline are important clinical consequences of knee OA. Because obesity is a major risk factor for this disease, weight loss should be a central component of treatment. Changes in both diet and physical activity are recommended to achieve weight loss. Physicians are in an ideal position to assess patients, motivate them, prescribe recommended courses of action, and provide long-term follow-up in the management of obesity.

References:

References1. Ettinger WH, Davis MA, Neuhaus JM, Mallon KP. Long-term physical functioning in persons with knee osteoarthritis from NHANES, 1: effects of comorbid medical conditions. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994;47:809-815.

2. Nevitt MC. Obesity outcomes in disease management: clinical outcomes for osteoarthritis. Obes Res. 2002;10(suppl 1):33S-37S.

3. Mehrotra C, Naimi TS, Serdula M, et al. Arthritis, body mass index, and professional advice to lose weight: implications for clinical medicine and public health. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27:16-21.

4. Felson DT, Zhang Y, Anthony JM, et al. Weight loss reduces the risk for symptomatic knee osteoarthritis in women: the Framingham Study. Ann Intern Med. 1992;116:535-539.

5. Minor MA. Impact of exercise on osteoarthritis outcomes. J Rheumatol Suppl. 2004;70:81-86.

6. American College of Rheumatology Subcommittee on Osteoarthritis Guidelines. Recommendations for the medical management of osteoarthritis of the hip and knee: 2000 update. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:1905-1915.

7. Messier SP, Loeser RF, Miller GD, et al. Exercise and dietary weight loss in overweight and obese older adults with knee osteoarthritis: the Arthritis, Diet, and Activity Promotion Trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:1501-1510.

8. Rejeski WJ, Focht BC, Messier SP, et al. Obese, older adults with knee osteoarthritis: weight loss, exercise, and quality of life. Health Psychol. 2002;21:419-426.

9. Miller GD, Nicklas BJ, Davis C, et al. Intensive weight loss program improves physical function in older obese adults with knee osteoarthritis. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2006;14:1219-1230.

10. Rejeski WJ, Brawley LR, Ettinger W, et al. Compliance to exercise therapy in older participants with knee osteoarthritis: implications for treating disability. Med Sci Sports Exer. 1997;29:977-985.

11. O'Reilly S, Doherty M. Lifestyle changes in the management of osteoarthritis. Best Prac Res Clin Rheumatol. 2001;15:559-568.

12. Baker KR, Nelson ME, Felson DT, et al. The efficacy of home based progressive strength training in older adults with knee osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial. J Rheumatol. 2001;28:1655-1665.

13. Rejeski WJ, Craven T, Ettinger WH Jr, et al. Self-efficacy and pain in disability with osteoarthritis of the knee. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1996;51:24-29.

14. Rejeski WJ, Martin KA, Miller ME, et al. Perceived importance and satisfaction with physical function in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Ann Behav Med. 1998; 20:141-148.

15. O'Reilly SC, Muir KR, Doherty M. Knee pain and disability in the Nottingham community: association with poor health status and psychological distress. Br J Rheumatol. 1998;37:870-873.

16. Wadden TA, Osei S. The treatment of obesity: an overview. In: Wadden TA, Stunkard AJ, eds. Handbook of Obesity Treatment. New York: Guilford Press; 2002:229-248.

17. Latner JD, Stunkard AJ, Wilson GT, et al. Effective long-term treatment of obesity: a continuing care model. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2000;24:893-898.

18. Heshka S, Greenway F, Anderson JW, et al. Self-help weight loss versus a structured commercial program after 26 weeks: a randomized controlled study. Am J Med. 2000;109:282-287.

19. Wing RR. Behavioral weight control. In: Wadden TA, Stunkard AJ, eds. Handbook of Obesity Treatment. New York: Guilford Press; 2002:301-316.

20. Brownell KD. Appendix D: guidelines for being a good group member. The LEARN Program for Weight Management 2000. Dallas: American Health Publishing Co; 2000:277-281.

21. Felson DT, Naimark A, Anderson J, et al. The prevalence of knee osteoarthritis in the elderly: the Framingham Osteoarthritis Study. Arthritis Rheum. 1987;30:914-918.

22. Wadden TA, Berkowitz RI, Sarwer DB, et al. Benefits of lifestyle modification in the pharmacologic treatment of obesity: a randomized trial. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:218-227.

23. Perri MG, Nezu AM, Viegener BJ. Improving the Long-Term Management of Obesity: Theory, Research and Clinical Guidelines. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 1992:107-123.

24. Steinbrook R. Surgery for severe obesity. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1075-1079.