Article

Perilunate dislocation: Case studies of a frequently missed diagnosis

ABSTRACT: If enough force is applied in a wrist ligament injury, aperilunate dislocation may occur. Physicians can readily make thediagnosis, but the injury may be missed in the initial evaluation. Withprompt recognition and intervention, the incidence of permanentdisability may be lessened. Acute carpal tunnel syndrome may accompanyperilunate injuries and frank dislocations. The scapholunateand lunotriquetral ligaments confer significant structural stabilityand help maintain the anatomical relationships of the carpal bones;when they are compromised, structural integrity is lost.Visual inspectionis critical to the physical examination. Neurovascular statusshould be determined and documented. Radiographic evaluationis recommended for all hand injuries. All perilunate dislocationsfirst need to be closed reduced, followed by surgical treatment.(J Musculoskel Med. 2008;25:390-395)

ABSTRACT: If enough force is applied in a wrist ligament injury, a perilunate dislocation may occur. Physicians can readily make the diagnosis, but the injury may be missed in the initial evaluation. With prompt recognition and intervention, the incidence of permanent disability may be lessened. Acute carpal tunnel syndrome may accompany perilunate injuries and frank dislocations. The scapholunate and lunotriquetral ligaments confer significant structural stability and help maintain the anatomical relationships of the carpal bones; when they are compromised, structural integrity is lost. Visual inspection is critical to the physical examination. Neurovascular status should be determined and documented. Radiographic evaluation is recommended for all hand injuries. All perilunate dislocations first need to be closed reduced, followed by surgical treatment. (J Musculoskel Med. 2008;25:390-395)

Wrist ligament injuries usually result from a fall onto an outstretched hand.1 If enough force is applied, a perilunate dislocation may occur-the carpal ligaments may become severely damaged and the lunate can dislocate from its facet on the distal radius. Fractures and neurological injuries also may occur within the spectrum of perilunate dislocations.

Physicians often can readily make the diagnosis of perilunate dislocations. In some cases, however, these injuries are missed in the initial evaluation.

An estimated 2.5% of emergency department (ED) visits in the United States are for wrist injuries.2 Of these, about 10% are perilunate dislocations and carpal fracture dislocations.3 The diagnosis of perilunate and lunate dislocations is missed initially in up to 25% of cases, and the resultant delay of treatment adversely affects clinical results.4 Long-term outcomes for patients with these injuries can be poor because of damage to the ligamentous architecture of the carpus. With prompt recognition and intervention, however, the incidence of permanent disability may be lessened and patients may approach near-normal hand function.5

Acute carpal tunnel syndrome (ACTS) may accompany perilunate injuries and frank dislocations when there is severe trauma to the wrist.6 The defining features include a rapid onset of numbness and paresthesia in the median nerve distribution. Because unresolved ACTS is an orthopedic emergency, early diagnosis and prompt referral improve clinical results and long-term patient outcomes.

In this article, we describe 2 cases of perilunate dislocation in which the diagnosis was not made initially and the patient presented with neurological signs consistent with ACTS. We provide a schema to facilitate diagnosis that involves recognizing the bony and neurological injuries and describe approaches to management, including referral to an orthopedist for prompt surgical treatment.

CASE PRESENTATIONS

Case 1: Snowboarding

A 17-year-old right hand–dominant adolescent boy sustained an injury to his right wrist while snowboarding. He was executing an extreme jump and landed primarily on his outstretched right upper extremity. The patient experienced immediate wrist pain and hand numbness. Results of wrist radiographs obtained at the local ED were interpreted as normal. A diagnosis of a wrist sprain was made, and the patient was given a splint and discharged.

Four days after the injury, the patient was further evaluated in a specialty hand clinic. He complained of pain and limited range of motion in the right wrist and digits and reported numbness and paresthesia in the right median nerve distribution.

On examination, the patient's hand was swollen and deformity was noted about the wrist. Active range of motion in the digits was limited significantly. Sensation was diminished to light touch in the median nerve distribution. Capillary refill was brisk, and pulses were palpable in the radial and ulnar arteries.

The original radiographs obtained in the ED were reviewed (Figure 1), and a transscaphoid perilunate fracture dislocation (a scaphoid fracture combined with the perilunate injury) was noted. The patient was scheduled for surgery that day.

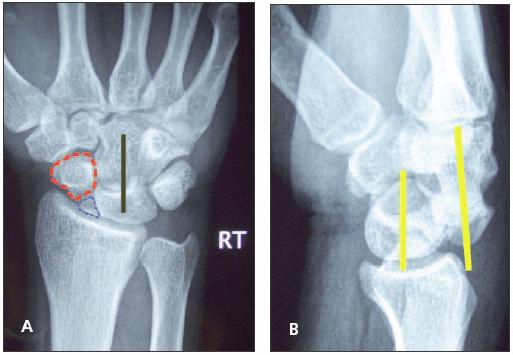

Figure 1

–

A posteroanterior (PA) radiograph of patient 1 demonstrates a scaphoid waist fracture (A). The proximal pole of the scaphoid is outlined in blue dots, and the distal tubercle is outlined in red dashes. The ring sign, formed by the cortex of the scaphoid viewed while flexed, is noted within the distal tubercle. The collinear alignment of the capitate and lunate is demonstrated with a solid black line. A lateral radiograph of patient 1 demonstrates dorsal dislocation of the capitate from the lunate (B). The yellow lines depict the longitudinal axes of the 2 carpal bones. The normal alignment of these bones when viewed in the lateral projection is collinear. Their intercarpal alignment also is normally collinear with the long axis of the radius. When compared with the PA projection in this patient, the lateral view offers greater insight into the injury's severity.

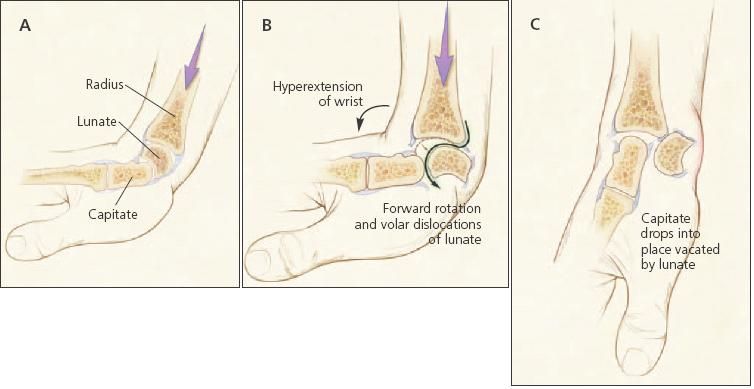

Figure 3 – In perilunate dislocations, the lunate dislocates volarly (off the distal radius) into the carpal canal (A to B to C).

Case 2: Physical altercation

A 32-year-old right hand–dominant woman presented to the ED with complaints of right wrist pain, deformity, and hand numbness. The patient reported a fall onto her outstretched right upper extremity during a physical altercation the previous night. She had presented to a local ED within 12 hours of the injury, and a diagnosis of radial and ulnar styloid fractures was made. She received a splint and was discharged and advised to see a hand surgeon for outpatient care.

The patient's pain and numbness worsened, resulting in her presentation to a second ED. On examination, her wrist demonstrated marked deformity. Active range of motion was absent in the wrist and significantly diminished in the digits. She reported decreased sensation and paresthesia in the median nerve distribution of her right hand. Capillary refill was brisk, and the radial and ulnar artery pulses were palpable.

Radiographic evaluation was repeated in our ED. X-ray films demonstrated both radius and ulnar styloid fractures and a volar perilunate dislocation. In this injury pattern, the scaphoid, triquetrum, and distal carpal row are dislocated volarly. The patient was taken to the operating room that day.

PATHOMECHANICS

The carpus is arranged in 2 rows of bones interposed between the distal radius and ulna and the base of the metacarpals (Figure 2). The distal row consists of the trapezium, trapezoid, capitate, and hamate; the proximal row is composed of the scaphoid, lunate, and triquetrum. The pisiform is a sesamoid bone that resides within the substance of the flexor carpi ulnaris; it does not contribute significantly to carpal stability.

Figure 2 –

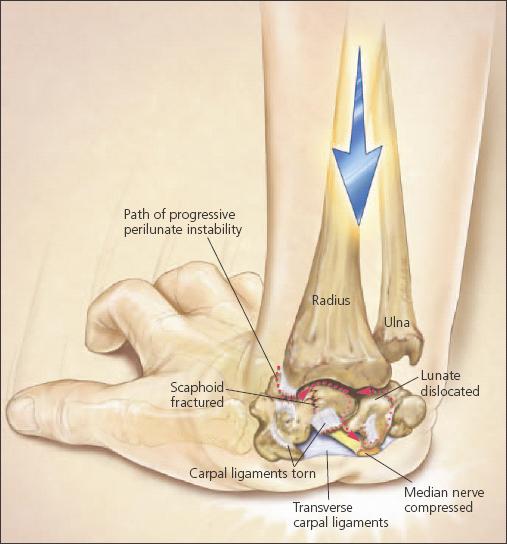

The diagnosis of perilunate dislocations can be missed in the initial patient evaluation. The carpus is arranged in 2 rows of bones interposed between the distal radius and ulna and the base of the metacarpals; the scapholunate and lunotriquetral ligaments confer significant structural stability. In Mayfield's progressive perilunate instability, extended and ulnar deviated wrists are loaded with increasing forces across the radiocarpal joint (dashed line). As the forces increase, a pattern of ligamentous injury emerges that begins at the radioscaphoid interval; proceeds through the scapholunate space and onto the lunotriquetral articulation; and completes the loop by traversing the radiolunate articulation, resulting in dislocation of the lunate that forces it volarly into the carpal canal.

The proximal carpal row is known as the intercalated segment because it is free of tendon attachments. Its motion is determined by the forces that the extrinsic tendons apply to the distal carpal row and metacarpals; intrinsic or intracapsular ligaments determine its stability.

The scapholunate and lunotriquetral are 2 of the most important ligaments in the carpus. They confer significant structural stability and help maintain the anatomical relationships of the carpal bones. When they are compromised, the structural integrity of the intercalated segment is lost and the lunate may displace or angulate.

The median nerve is located volar to the lunate. When the ligaments of the intercalated segment are disrupted in severe injuries, the lunate may migrate volarly into the carpal canal (Figures 2 and 3). This motion results in a mass effect on the median nerve that results in a reduction in capillary blood flow below the level necessary for median nerve function. The acute swelling caused by the injury also may induce ACTS.

An axial load to the carpus in which ligamentous injury has occurred results in a disturbance of the normal anatomical relationships. Such an injury occurs in a defined pattern.7,8 In a study performed by Mayfield and associates7 on cadaveric specimens, extended and ulnar deviated wrists were loaded with increasing forces across the radiocarpal joint. As the forces increased, a pattern of ligamentous injury emerged that began at the radioscaphoid interval, proceeded through the scapholunate space onto the lunotriquetral articulation, and completed the loop by traversing the radiolunate articulation (see Figure 2). This last, and most severe, injury results in dislocation of the lunate that forces it volarly into the carpal canal.

Classic CTS often develops over a sustained period. In this long-term scenario, the median nerve undergoes slow compression and restriction of arteriole blood flow. When these events occur over a long period, there is adaptation of the median nerve and compensation by local vascular supply. Although the nerve's viability ultimately is jeopardized because these events do not occur acutely, there is sufficient time for the surgeon to intercede.

When median nerve irritation is caused by a perilunate dislocation, it is brought about by the direct trauma of the injury, postinjury edema and, possibly, hematoma in the carpal tunnel. After closed reduction, no acute surgical treatment is necessary, as long as the median nerve symptoms dissipate. However, if the median nerve symptoms worsen in the acute period (6 to 24 hours), carpal tunnel decompression is urgently required.

DIAGNOSIS

The diagnosis of perilunate dislocation may be made after a thorough history and physical examination are completed and correlated with radiographic study results. The patient's handedness should be noted to understand his or her potential disability. The patient's occupation and hobbies should be investigated, especially those that require a great deal of manual dexterity. The mechanism of injury should be detailed and questions should be asked (eg, What was the height of the fall?) to facilitate an understanding of the force on the extremity. Diagnosis of additional injuries should be made, and those injuries should be managed appropriately.

Starting the physical examination in a logical, routine manner is useful. We prefer to begin with examination of the normal, uninjured anatomy and then proceed to the affected areas. In upper extremity trauma, the entire upper extremity should be examined.

Visual inspection is critical. The initial hand examination does not require physical contact between examiner and patient; visual inspection and compliance with examiner requests often are sufficient to provide a short differential: Are there obvious deformities caused by fracture or dislocations? Is there edema? Do open wounds or fractures complicate the presentation?

The neurovascular status of the limb should be determined and documented carefully. Special attention should be paid to hand sensation, as determined by 2-point discrimination, and discrimination of sharp and blunt touch. A 2-point discrimination test result of 5 to 7 mm is normal; testing can be performed quickly with a twisted paper clip.

Motor testing should include not only peripheral nerves but also those specific to the cervical spine roots, because injuries to these structures are not uncommon in traction injuries. The examination often overlaps because combined traction and penetrating trauma can offer a mixed clinical picture.

The vascular status of the limb should be evaluated. Determination of capillary refill and palpable arterial pulses is essential. Attention should be paid to the temperature of the digits.

The American Society for Surgery of the Hand recommends radiographic evaluation for all hand injuries. Standard views include the posteroanterior (PA) and lateral. Oblique views may provide an additional perspective to rule out occult fractures. If there are irregularities, x-ray films of the contralateral side should be obtained for comparison.

In the PA projection, attention is directed to the digits as well as the metacarpals and carpus. Proper alignment of the bones needs to be evaluated critically. In the carpus, 3 distinct arcs-Gilula arcs-are examined for continuity.8 They lie at the proximal end of the distal carpal row and at the distal and proximal ends of the proximal row. The interval between the scaphoid and lunate is evaluated for a diastasis; if the interval is increased beyond 3 mm, injury to the scapholunate ligament should be suspected.9

Scaphoid fractures, perilunate instability, and frank dislocation are common in forceful axial load injuries to the carpus and occur in a specific pattern. Radiographic clues to the possibility of a perilunate injury include a scaphoid fracture and radial and ulnar styloid fractures. When a scaphoid fracture is suspected, ulnar deviation radiographs should be obtained to better evaluate the scaphoid. In the case of perilunate dislocation, the lunate may have a triangular rather than its normal quadrangular appearance. There may be overlap of the proximal and distal rows, and Gilula arcs will be broken.8

MANAGEMENT

All perilunate dislocations first need to be closed reduced, followed by surgical treatment.10 The goals are anatomical reduction of the dislocation, repair of damaged ligaments and, when fractures are present, internal fixation. The dislocated lunate displaces volarly, toward the median nerve, which it may compress within the carpal canal.

In patients with a perilunate dislocation and no symptoms of ACTS, closed reduction can be performed and the patient may be observed for 1 to 2 hours. If patients are stable, they may be discharged for elective operative treatment of the ligamentous injury. Those with median nerve paresthesia undergo closed reduction in a similar fashion, followed by a period of observation for resolution of symptoms. If symptoms remain or worsen, this is a case of ACTS; the patient should be taken to the operating room for emergent decompression of the carpal tunnel and fixation of the dislocation.

An extensile ulnar approach to the carpal tunnel is recommended to facilitate complete release of the median nerve and full exposure of the volar aspect of the carpus. The dislocated lunate should be reduced in its fossa on the radius and pinned with a smooth Kirschner wire. The tear in the volar ligaments that invariably is seen with lunate dislocation occurs in the space of Poirer, an inherently weak area on the volar aspect of the carpus. We recommend that this rent be repaired with nonabsorbable suture.

Dorsal ligament injuries also require repair. A longitudinal incision is made on the dorsum of the wrist, and the ligaments are incised in line with their fibers. The energy from the injury often hastens the surgical dissection. The lunate, once reduced, is held within its fossa with Kirschner wires. The remainder of the carpus is then assembled about this keystone.

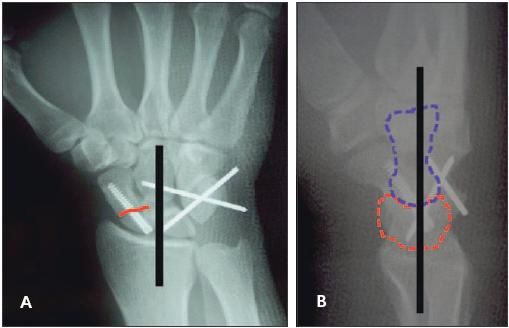

Provided the scaphoid is intact, it provides a foundation for the radial carpus and hand, notably the thumb. In the case of the first patient, the scaphoid was fractured and displaced at the waist, requiring surgical fixation. This fracture is addressed in a variety of ways. According to the location and orientation of the fracture, a guide wire is passed along the longitudinal axis of the scaphoid and a headless compression screw is delivered from proximal to distal or distal to proximal (Figure 4). Should the fracture occur closer to the proximal pole of the scaphoid, delivering the screw from the proximal end to ease reduction and fixation has been recommended. In addition, the dorsal surgical dissection allows for greater exposure. Also, the intercarpal and radiocarpal ligaments are repaired; this may require the use of suture anchors in the bone. The wounds are closed and a thumb spica splint is applied.

Figure 4 –

In this posteroanterior radiograph (A) obtained postoperatively in patient 1, the red line denotes the scaphoid fracture line,which is now reduced and internally fixed. The black line demonstrates the collinearity of the capitate, lunate, and radius. In a lateral radiograph (B) obtained postoperatively in patient 1, the blue dashed line outlines the capitate and the red dashed line outlines the lunate. The black line demonstrates the collinearity and normal alignment of the capitate, lunate, and radius.

The splint is maintained for 10 to 14 days and then changed to a long arm thumb spica cast after the sutures are removed. The long-arm cast is kept in place for 6 weeks, followed by a short-arm thumb spica cast for 4 weeks. The pins are removed at 10 to 12 weeks. Then, a removable splint is allowed and occupational therapy is started. Range of motion therapy is continued for 6 weeks, and then muscle strengthening exercises are added.

The patient in case 1 achieved an excellent result 1 year postinjury. He has returned to normal activities and enjoys full wrist motion. His strength is good and sensation normal. His only complaint is mild ache with heavy use.

The patient in case 2 achieved a good result 6 months after injury. She has improvement in median nerve function and minimal discomfort with moderate limitations in motion. The patient's ability to perform activities of daily living has returned.

SUMMARY

Much work has been done to study the nature of perilunate injuries and the clinical outcomes of treatment. Mayfield and colleagues,7 Niazi,11 and other investigators have helped determine the anatomical basis of ligamentous injuries to the carpus. Herzberg and Forissier12 monitored 14 transscaphoid perilunate fracture dislocations for 8 years postoperatively; 57% of patients had excellent or good results, but missed injuries did not fare as well.

Inoue and Shionoya5 evaluated patients with chronic, unreduced perilunate injuries. Patients benefited from open reduction with internal fixation performed within 2 months of injury. After 2 months, however, patients were best treated with proximal row carpectomy, which helps restore some function but is regarded largely as a salvage procedure intended primarily to lessen pain.5

Perilunate injuries and frank dislocations may be complicated by ACTS. The orthopedic surgeon's goal is to restore carpal alignment and provide a foundation for regaining strength and function in the upper extremity. Early diagnosis and prompt referral improve clinical results and long-term patient outcomes.

References:

References

- 1. Murray PM. Dislocations of the wrist: carpal instability complex. J Am Soc Surg Hand. 2003;3:88-99.

- 2. Larsen CF, Lauritsen J. Epidemiology of acute wrist trauma. Int J Epidemiol. 1993;22:911-916.

- 3. Meldon SW, Hargarten SW. Ligamentous injuries of the wrist. J Emerg Med. 1995;13:217-225.

- 4. Herzberg G, Comtet JJ, Linscheid RL, et al. Perilunate dislocations and fracture-dislocations: a multicenter study. J Hand Surg. 1993;18A:768-779.

- 5. Inoue G, Shionoya K. Late treatment of unreduced perilunate dislocations. J Hand Surg. 1999;24B:221-225.

- 6. Mack GR, McPherson SA, Lutz RB. Acute median neuropathy after wrist trauma: the role of emergent carpal tunnel release. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1994;300:141-146.

- 7. Mayfield JK, Johnson RP, Kilcoyne RK. Carpal dislocations: pathomechanics and progressive perilunar instability. J Hand Surg. 1980;5A:226-241.

- 8. Gilula LA. Carpal injuries: analytic approach and case exercises. AJR. 1979;133:503-517.

- 9. Bednar JM, Osterman AL. Carpal instability: evaluation and treatment. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1993;1:10-17.

- 10. Kozin S. Perilunate injuries: diagnosis and treatment. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1998;6:114-120.

- 11. Niazi TB. Volar perilunate dislocation of the carpus: a case report and elucidation of its mechanism of occurrence. Injury. 1996;27:209-211.

- 12. Herzberg G, Forissier D. Acute dorsal trans-scaphoid perilunate fracture-dislocations: medium-term results. J Hand Surg. 2002;27B:498-502.