Article

“Prehab” prevents injuries in athletes and dancers

Three-dimensional (3D) computer motion analysis has emerged in recent years as a valuable diagnostic tool for elite athletes and coaches to combat injuries and maximize biomechanical function to improve athletic performance.

Three-dimensional (3D) computer motion analysis has emerged in recent years as a valuable diagnostic tool for elite athletes and coaches to combat injuries and maximize biomechanical function to improve athletic performance. Using quantitative analytical tools helps researchers and coaches better understand how an athlete can alter his or her movements to achieve these goals. For example, orthopedists have surmised that knee disorders (eg, patellofemoral syndrome) may result from inadequate turnout techniques, failure to sink into the heels during a jump, overpronation, or decreased hip external rotation. 3D analysis creates a quantitative assessment to provide qualitative and practical guidance on how to improve techniques and reduce the probability of injury.

Staff members at the University of Florida Orthopaedics and Sports Medicine Institute (OSMI) have integrated 3D computer motion analysis into a proactive approach known as prehabilitation, or "prehab," in an attempt to identify, manage, and prevent injuries during the athletic preseason. Analysis is essential in the identification stage of the process. Once the issues pertaining to injury prevention or technical accuracy are identified, the athletes can begin to modify their movements accordingly.

More recently, the OSMI staff have begun to apply the technology to preventing dance injuries and helping dancers, their instructors, and choreographers produce technically sound performances. The art of dance pushes the mechanical limits of the human body. Performing dancers seem to move effortlessly across the stage while, in fact, they exert extreme effort in achieving flexibility, strength, and control. As dancers train relentlessly in the pursuit of their perfected motions, their intense regimens often result in complex injuries that have shortened the professional career of many, in areas of dance ranging from performance to ballet. As a result, the orthopedic community is reporting a growing number of acute and degenerative musculoskeletal injuries in this arena.

Injuries in dancers occur most frequently in the ankles, feet, knees, hips, and back. In a study of mixed-level ballet dancers, 22% of injuries occurred in the ankle, 20% in the foot, and 17% in the knee. Grand plis, movements that involve deep knee bends and external hip rotation, have been cited as a significant contributor to damaged connective tissue within the knee and chronic lower limb injuries.

Similar studies have highlighted these sites as being particularly vulnerable to injury but have also included back injuries, particularly in professional dancers. Other common disorders include chronic foot pain and inflammation, particularly in ballet dancers wearing pointe shoes.

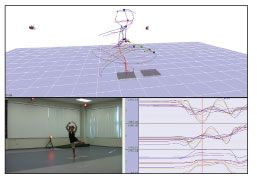

By using 3D motion analysis, researchers, dancers, and instructors can begin to understand where and how these injuries originate. During the identification stage, OSMI staff members surround the dancer with a high-speed digital 3D motion capture system (Figure). The 12-camera system reads reflections from 22 markers placed strategically on the dancer's body. As the infrared cameras capture the dancer's movements-at a rate of up to 500 frames per second-imaging software simultaneously translates these data into a 3D model and stores the athlete's coordinates in a

database for analysis and comparison.

Figure–During the identification stage of 3-dimensional motion analysis, Orthopaedics and Sports Medicine Institute staff members surround the dancer with a high-speed digital 3D motion capture system. The athlete's coordinates are stored in a database for analysis and comparison.

As the dancer performs, 2 engineering force plates on the ground measure the amount of force she exerts. Having this ground reaction force data helps analysts ascertain how the dancer's body interacts with the ground to reveal imbalances during movements.

After the performance is completed, laboratory engineers use the 3D software to calculate measurements. The performer's movements can be reviewed to identify potentially injurious ones.

In dance, data points that can be calculated, compared, and reviewed include maximum hip rotation, take-off force, and limb extension. Researchers at OSMI have begun to calculate the stability of a turn compared with that of a normal stance, the balance of weight between the right and left legs throughout a repeated jump and the fatigue that is involved, and the body-centeredness of a fouett or flip turn.

By analyzing the information captured in the laboratory, researchers and analysts can begin to optimize a performer's biomechanics positioning, reduce the damage in affected areas, and maximize performance. For ballet dancers who want to maximize the amount of torque generated in a pirouette, improve the height of their jump, or fine tune a grand jet, for example, comparative motion analysis can help determine the footwork, extension, and positioning needed to accomplish these objectives.

Engineers also can assess a dancer's maximum hip, knee, and ankle angles; hang time; and height throughout a motion and compare them with the movement of a professional dancer. By testing multiple professionals, analysts can begin to identify commonalities in their performances and motions and establish a broader baseline. These unique attributes can then set the standard for specific motions and be used for comparison of other professionals or aspiring amateurs.

The OSMI researchers have demonstrated that prehab conducted in this manner can be effective at reducing injuries and improving performance. Prehab enables staff members to identify musculoskeletal instabilities and recommend appropriate training regimens to prevent injury or help postsurgical rehabilitation. In addition, prehab motion analysis can help dancers hone their techniques and improve aesthetics while maximizing their performance.