Article

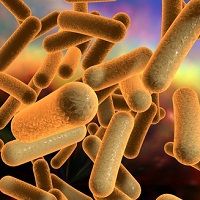

Prevention and Control Strategies for Clostridium difficile

Author(s):

An epidemiologist shares his knowledge about Clostridium difficile prevention and control.

In a sit-down interview with MD Magazine®’s sister publication, Contagion®, Gonzalo Bearman, MD, MPH, professor of medicine and hospital epidemiologist in the Department of Internal Medicine and Infectious Diseases, Virginia Commonwealth University, explains what is known about Clostridium difficile prevention and control.

To begin with, Bearman says that bloodstream infections associated with central lines and urinary tract infections associated with catheters are much more effectively prevented than C. difficile, but the reasons why are not entirely clear. “Much of C. difficile is probably coming from diverse reservoirs, it’s probably coming from the community and the environment and [it’s] not necessarily hospital-acquired,” he explains. “So, the degree to which we can stop the transmission or alter the development of disease is still not well-defined.”

While there is still much to understand about its transmission, there are straightforward, cost-effective strategies in the hospital setting that can be used to control C. difficile. Referred to as a “bundled approach” to infection control, these prevention techniques include handwashing, early detection, patient isolation, and proper and/or heightened disinfection throughout the infected patient’s hospitalization. When these infection-control procedures are used in conjunction, Bearman points out, they form an economical bundled approach strategy to C. difficile control that is far less expensive than new technologies, such as ultraviolet light disinfection robots.

Although the bundled approach is far less expensive than a disinfection robot, Bearman also believes that they have limitations, and that their effectiveness needs to be consistently assessed. If desired outcomes are not where they should be and processes are not improving, then the bundled approach being used needs to be rethought. “My approach is, we start with a bundled strategy, and if it’s not working, we need to be nimble, and change our strategy accordingly,” Bearman offers. “I’m not saying that we should never do active detection and isolation for Clostridium difficile; I think it’s reasonable, particularly if your bundled approaches are failing, and if you’re certain that you’re doing all of the bundled elements within that approach properly.”

Proper antibiotic use and management is a critical component of the bundled approach to C. difficile prevention, and controlling the misuse of antibiotics could have the most significant impact on decreasing C. difficile incidence. “In studies that have already been published or are now coming out, when certain antimicrobials, such as fluoroquinolones or cephalosporins, are controlled or restricted, the rates of Clostridium difficile infection go down,” Bearman points out. “I think that’s a critically important component to a bundled approach.”

Still up for debate in the infection control conversation is whether prevention protocols driven by nurses, who are often the first to suspect a possible case of C. difficile through their position on the front line of patient care, are effective and should be implemented in healthcare settings as a standard of care. Bearman, who does follow nurse-driven prevention protocols in his institution, believes that nurses have an invaluable part to play in an overall prevention strategy. “The theory is that nurses, because they’re by the patients more than anyone else really, are the first to recognize a diarrheal syndrome. They should be given the latitude and freedom to order C. difficile tests within certain parameters to make an early diagnosis,” Bearman argues. “By making an early diagnosis it leads to earlier treatment, earlier isolation, and potentially [could] decrease the risk of transmission to other patients.”

Because there are a range of strategies that can be employed to prevent C. difficile, Bearman believes each healthcare system and setting must decide what is best for its own situation. “I think the aggressiveness of a [Clostridium] difficile strategy should really reflect the degree at which C. difficile is a problem in a healthcare system. There is a range of strategies that could be done,” he explains. “Certainly, for an institution that has a high level or high rate of C. difficile infection, some authorities, some infection preventionists, want to be more aggressive, not only with isolation but also with screening patients on admission to see whether or not they’re colonized with C. difficile, [so as] to isolate them, properly. That’s not necessarily the standard of care, but [it’s] certainly done by some institutions.”