Article

Rethinking Hyperkalemia Management: A Practice Change Approach

Author(s):

Globally, an estimated 850 million and 64 million people live with some form of kidney disease and heart failure (HF), respectively. Patients with chronic conditions of HF, chronic kidney disease (CKD), and diabetes, as well as those taking certain medications like RAAS inhibitors, are at an increased risk of developing hyperkalemia (HK) - a higher-than-normal potassium level in the blood.

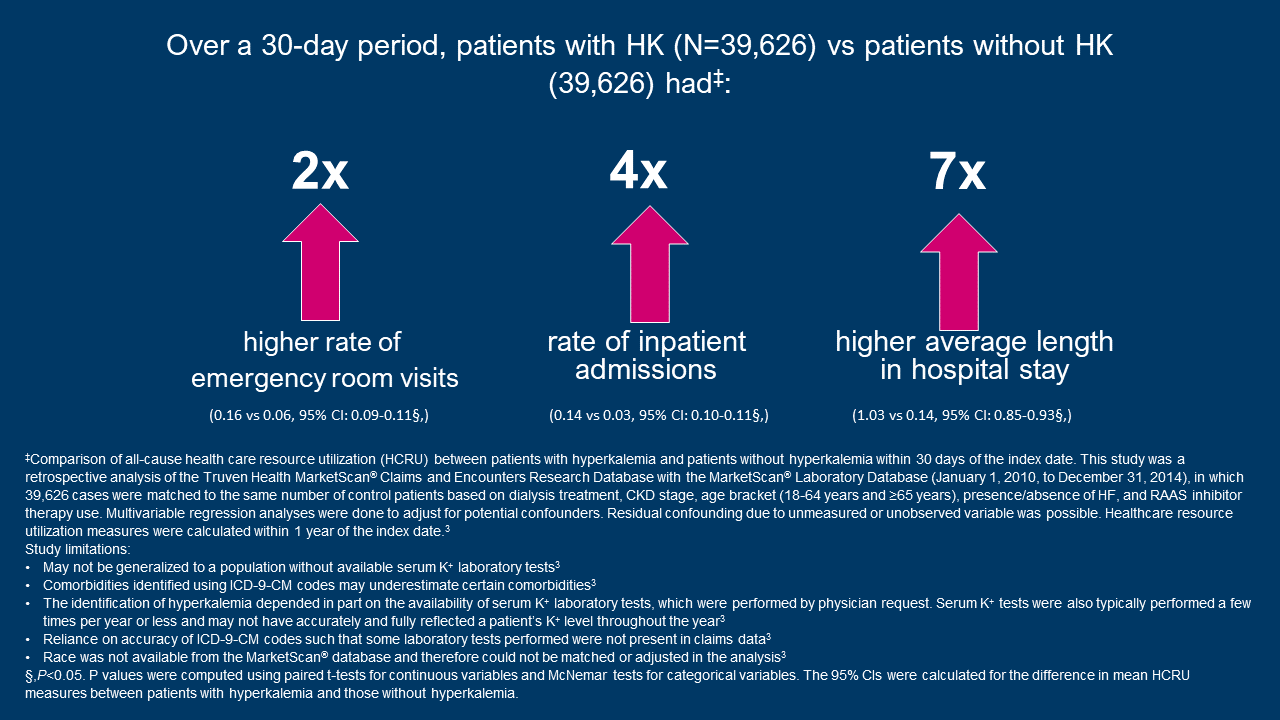

HK can be a chronic condition and has been associated with increased hospitalizations and death. In a US-based retrospective study from integrated health delivery networks, HK was found to be an independent risk factor for all-cause mortality in almost 1 million patients including those with CKD, HF, and/or diabetes.1* In a second US-based retrospective analysis of a medical claims database of 39,626 matched pairs of patients with or without HK, 40% of patients with HK experienced 2 or more hyperkalemic events during the 1-year post index period.2†

“It is important to take hyperkalemia seriously, as it is a potentially fatal condition,” says Pamela Kushner, MD, FAAFP, a primary care physician (PCP) and clinical professor at the University of California Irvine Medical Center. “People with CKD, and/or HF, or other cardio-renal comorbidities, if they are diagnosed with chronic hyperkalemia, they may need long-term management due to the underlying condition. As a PCP, I often support my patients with a diagnosis of hyperkalemia, and I make regular potassium monitoring a part of their long-term care plans as soon as possible.”

RAASi therapy are a group of medicines recommended by the 2021 European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the 2022 American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology/Heart Failure Society of America (AHA/ACC/HFSA) for the treatment of patients with HF. The 2022 and 2021 Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Clinical Practice Guidelines recommend the use of ACEi or ARB for the treatment of patients with CKD and hypertension with/or without diabetes.

Javed Butler, MD, MPH, MBA, a cardiologist at Baylor Scott and White Health in Dallas, Texas, and a professor of medicine at the University of Mississippi Medical Center in Jackson, Mississippi, explains, “RAASi therapy is one of the most important management approaches for HF patients. These lifesaving treatments reduce the number of HF-related hospitalizations and reduce mortality risk.”

Unfortunately, RAASi therapy has been associated with HK, which is often treated with a reduction or discontinuation of RAASi therapy. In a US-based medical records analysis of patients prescribed a RAASi, including ACE inhibitors, ARBs, direct renin inhibitors and select MRAs, mortality was at least 2x higher for patients with CKD whose RAASi had been reduced (20.3%) or discontinued (22.4%) compared to patients on maximum RAASi doses (9.8%).‖

Given the impact that HK can have on patients, a long-term and continued approach to treating HK is needed.

A low K+ diet is a non-therapeutic approach to managing HK, however, there is a lack of high-quality evidence demonstrating its effectiveness as a HK management strategy. A major contributor to HK in patients with advanced CKD is inadequate excretion of K+ through the kidneys, so reduction in dietary K+ alone may not be sufficient. In addition, a low K+ diet may deprive patients of important nutrients or could conflict with some aspects of a heart-healthy diet. Dietary modifications can be challenging to achieve and adhere to in patients with CKD as well.

There are several guideline recommended options for managing HK which include both therapeutic and non-therapeutic approaches.

According to one practice point from the 2021 KDIGO clinical practice guidelines for the management of blood pressure in CKD, HK associated with RASi use can often be managed by measures to reduce the serum K+ levels rather than decreasing dose or stopping RASi. Strategies to control chronic HK include dietary potassium restriction; discontinuation of potassium supplements, certain salt substitutes, and hyperkalemic drugs; adding potassium-wasting diuretics; and oral potassium binders. In CKD patients receiving RASi who develop HK, the latter can be controlled with newer oral K+ binders in many patients, with the effect that RASi can be continued at the recommended dose.

The 2022 KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline for Diabetes Management in CKD recommends that treatment with an ACEi or ARB be initiated in patients with diabetes, hypertension, and albuminuria, and that these medications be titrated to the highest approved dose that is tolerated. Hyperkalemia associated with the use of an ACEi or ARB can often be managed by measures to reduce serum potassium levels rather than decreasing the dose or stopping the ACEi or ARB immediately. Measures to manage HK include: review concurrent drugs including over the counter and herbal drugs as well as supplements to avoid/discontinue drugs that impair K+ excretion, moderate potassium intake, and consider diuretics, sodium bicarbonate, and potassium binders. Potassium binders should be considered to decrease serum K+ levels after other measures have failed, rather than decreasing or discontinuing ACEi or ARB treatment.

Among patients with HF, the ESC 2021 guideline refers to the use of potassium binders for the treatment of acute and chronic HK in patients with HF which may allow initiation or uptitration of RAASi in patients with renal dysfunction or HK.

Rethinking Episodic Hyperkalemia Management in Support of Current Guideline Recommendations

HK can present as a single episode, but the reality for many patients with CKD is that their HK will, or already has, become a chronic condition. HK remains an ongoing threat in patients with comorbidities such as HF, CKD, and/or diabetes, as many within this patient population have recurrent HK episodes.

“Viewing hyperkalemia as a chronic or recurrent condition is an important step for patients and their care teams to ensure an optimal approach to ongoing management,” says Professor Kam Kalantar-Zadeh, MD, MPH, PhD. “There are guideline recommended ways for nephrologists and other clinicians to manage their patients’ hyperkalemia episodes over the long-term, which include options in addition to potassium restrictive diets, which may deprive patients of healthy fruits and vegetables, especially those with CKD.”

Physicians should take a guideline-informed approach when managing HK, including RAASi-associated HK, especially in patients with HF, CKD and/or diabetes.

*Retrospective study of 911,698 patients from multiple integrated health delivery networks (Humedica). Control group included 338,297 individuals without known HF, CKD, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, or hypertension. Patient data came from private insurers, Medicare and Medicaid users, and uninsured individuals.1

†Based on a retrospective analysis of a medical claims database with 39,626 matched pairs of patients with or without hyperkalemia. Patients with hyperkalemia were defined as having 2 laboratory tests with a serum potassium level >5.0 mEq/L, at least 1 diagnosis code corresponding to hyperkalemia (ICD-9-CM code: 276.7), or at least 1 prescription fill of SPS.3

‖Based on data from an analysis of medical records of patients 5 years and older with at least 2 serum K+ measurements from the Humedica database. Patients with ESRD at the index date were excluded from outcomes analyses. Patients were included if they had at least 1 outpatient prescription for a RAAS inhibitor, including ACE inhibitors, ARBs, direct renin inhibitors, and select MRAs. Patients were categorized by their last RAAS inhibitor dose level for the analysis of mortality, where maximum was defined as the labeled dose and submaximum was defined as any dose lower than the labeled dose. Mortality rates for the overall population (N=201,655) during the 12-month period were 4.1% for patients on maximum RAAS inhibitor dose, 8.2% for patients on submaximum dose, and 11.0% for patients who discontinued RAAS inhibitor therapy. Causality between RAAS inhibitor dose and adverse outcomes was not evaluated.4

References

- Collins AJ, Pitt B, Reaven N, et al. Association of serum potassium with all-cause mortality in patients with and without heart failure, chronic kidney disease, and/or diabetes. Am J Nephrol. 2017;46(3):213-221

- Data on File, REF-34835. AZPLP.

- Betts KA, Woolley JM, Mu F, Xiang C, Tang W, Wu EQ. The cost of hyperkalemia in the United States. Kidney Int Rep. 2018;3(2):385-393

- Epstein, Murray et al. “Evaluation of the treatment gap between clinical guidelines and the utilization of renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors.” The American journal of managed care vol. 21,11 Suppl (2015): S212-20.

US-68699 Last Updated 11/22