Article

Small Rises in Blood Sugar Cause Major Changes in Gene Expression In Pancreatic Beta Cells

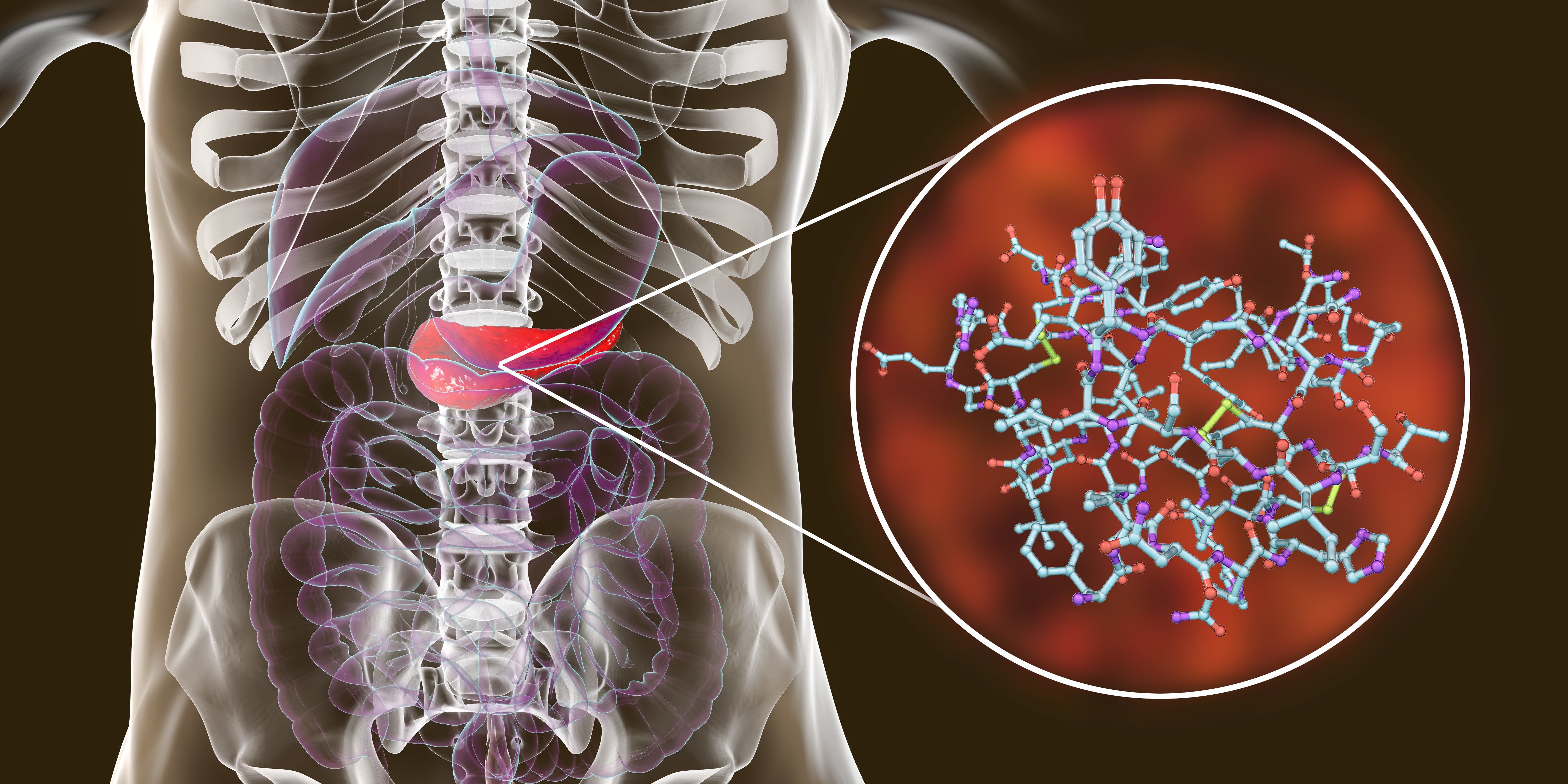

New research from the Joslin Diabetes Center helps illuminate the process of glucose toxicity in pancreatic beta cells. Observing the behavior of these cells in lab rats following parial pancreatectomy, researchers were able to observe how small consistent rises in blood sugar levels typical of pre-diabetes caused changes in gene expression that impeded the ability of beta cells to produce insulin.

Kateryna_Kon@AdobeStock_238594437

New research from the Joslin Diabetes Center helps illuminate the process of glucose toxicity in pancreatic beta cells.

Observing the behavior of these cells in lab rats following parial pancreatectomy, researchers were able to observe how small consistent rises in blood sugar levels typical of pre-diabetes caused changes in gene expression that impeded the ability of beta cells to produce insulin.

In a paper recently published in the journal Molecular Metabolism, Gordon Weir and his colleagues detailed changes in gene expression that could explain their loss of insulin-producing function, but also the progression of diabetic disease.

In healthy people with normal blood glucose levels, Weir explains, the body responds quickly to glucose with a big spike of insulin secretion. "If then you take people who have slightly higher glucose levels, above 100 mg/dl, which is still not even diabetes, this first-phase insulin release is impaired," he says. "And when the level gets above 115 mg/dl, it's gone. So virtually all the beta cells don't respond to that acute stimulus."

Weir and collaborators studied this same phenomenon in rats with partial pancreatectomy, and found that the rats' remaining beta cells secreted less insulin. They then used RNA sequencing reither four weeks or ten weeks after surgery to monitor gene expression "We found incredible changes in gene expression, and the higher the glucose, the worse the changes," Weir says.

Weir's team demonstrated that many of the critical genes responsible for insulin secretion were downregulated while the expression of normally suppressed genes increased. Also, there were marked changes in genes associated with replication, aging, senescence, stress, inflammation, and increased expression of genes controlling both class I and II MHC antigens suggesting that mild glucose elevations in the early stages of diabetes lead to phenotypic changes that adversely affect beta cell function, growth, and vulnerability.

For example, changes in MCH gene expression could make the beta cells a better target for autoimmune attack, and thus speed the progression of the disease. This finding may improve the understanding of the rapid death of beta cells that patients typically experience just before they are diagnosed with type 1 diabetes, Weir says. It also might shed light on the "honeymoon" period some people experience after diagnosis, in which their blood glucose levels are relatively easy to control. During this period, if insulin treatments can bring the remaining beta cells back down to only slightly elevated glucose levels, the cells can function much better, he says.

Glucose toxicity also might trigger the loss of first-phase insulin release as type 2 diabetes develops, Weir says. Immunologists often blamed this loss on inflammation of the beta cells, but other studies have shown that less than half of these cells appear to suffer from inflammation. "So somehow these beta cells with no evidence of inflammation end up not secreting properly," Weir says. "We think these higher glucose levels are causing the trouble."

More evidence for the role of higher blood glucose levels in type 2 diabetes comes from the subset of people undergoing gastric bypass surgery who are "cured" of diabetes and return to healthy blood glucose levels. "Their first-phase insulin release also comes right back to normal, which fits perfectly with our hypothesis," he says.

Full text of the article "Beta cell identity changes with mild hyperglycemia: Implications for function, growth, and vulnerability," can be found here: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.molmet.2020.02.002