Article

Transgender Men Receiving Testosterone at Greater Risk of Blood Clots

Author(s):

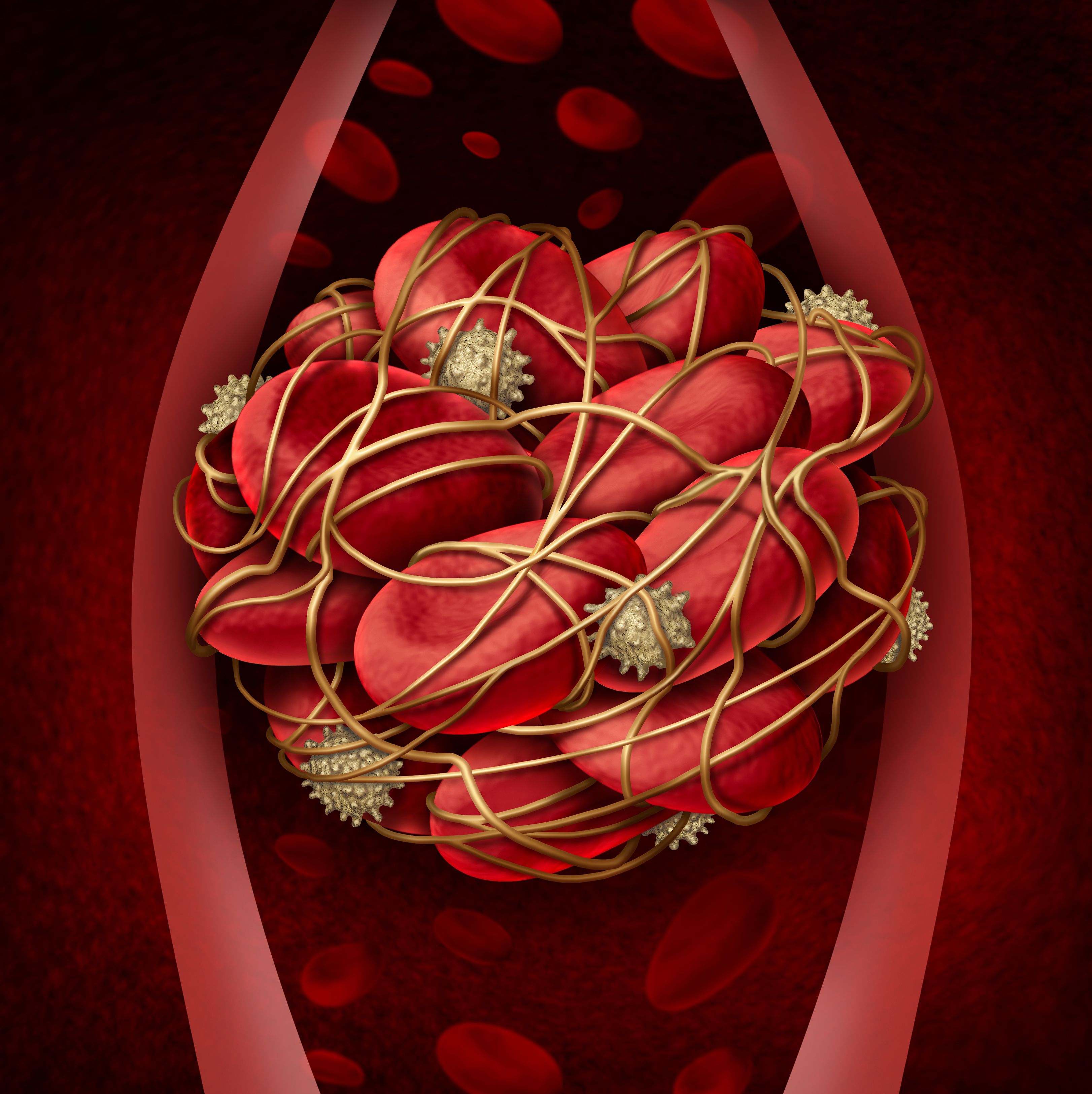

Data from a 20-year follow-up of gender diverse individuals indicate transgender men receiving testosterone therapy were at an 11% increased risk of developing erythrocytosis.

A 20-year follow-up study of gender diverse people suggests transgender men receiving testosterone therapy were at an 11% greater risk of developing blood clots.

Led by investigators from the Department of Endocrinology and Center of Expertise on Gender Dysphoria at Vrije Universiteit Medical Center, results of the study indicate patients saw the greatest increase of hematocrit during the first year and provide insight into potential avenues for mitigating this risk.

"Erythrocytosis is common in transgender men treated with testosterone, especially in those who smoke, have high body mass index (BMI) and use testosterone injections," said lead investigator Milou Cecilia Madsen, MD, of the VU University Medical Center Amsterdam in the Netherlands, in a statement. "A reasonable first step in the care of transgender men with high red blood cells while on testosterone therapy is to advise them to quit smoking, switch injectable testosterone to gel, and if BMI is high, to lose weight."

With testosterone therapy common among transgender men undergoing gender-affirming treatment, investigators sought to develop a greater understanding of the prevalence and predictors of erythrocytosis in these patients. To do so, the current study was designed as part of the Amsterdam Cohort of Gender Dysphoria (ACOG) study, which was conducted from 1972-2015 and contained data from 6793 people who visited the Center of Expertise on Gender Dysphoria.

For the purpose of the current study, investigators only included transgender men who started testosterone therapy and had at least one follow-up visit after starting testosterone therapy. Of note, the investigators excluded patients if they discontinued testosterone therapy during follow-up or if they were missing information related to the starting date of testosterone therapy or laboratory results.

Additionally, the study also allowed investigators access to information related to medication use, medical history, duration of hormonal treatment, testosterone administration route, BMI, tobacco use, alcohol use, and laboratory results of testosterone levels and hematocrit.

In total, 1073 patients were identified for inclusion in the study. The ACOG study included 2398 transgender men, but 431 were excluded due to a missing start date of hormone therapy and an additional 894 were excluded due to no available laboratory results. Of the 1073 included, the median age at the start of hormone therapy was 22.5 (IQR, 18.4-31.8) years and the mean BMI at the start of hormone therapy was 24.5 (SD, 5.5) years. Inv4estigaots noted 38% reported tobacco use and 8.6% reported having conditions associated with erythrocytosis—these included pulmonary conditions associated with erythrocytosis (7.6%), obstructive sleep apnea (0.7%), and polycythemia vera (0.4%).

For the purpose of analysis, investigators categorize patients based on hematocrit levels. These groups were defined as greater than 0.50 l/l, greater than 0.52 l/l, and greater than 0.54 l/l.

Upon analysis, results indicated erythrocytosis occurred in 11% of transgender men with hematocrit levels of 0.50 l/l, 3.7% of transgender men with hematocrit levels greater than 0.52 l/l, and 0.5% of transgender men with a hematocrit level greater than 0.54 l/l. Results of the analysis suggest tobacco use (OR, 2.2; 95% CI, 1.6-3.3), long-acting undecanoate injections (OR, 2.9; 95% CI, 1.7-5.0), age at initiation of hormone therapy (OR, 5.9; 95% CI, 2.8- 12.3), BMI (OR, 3.7; 95% CI, 2.2-6.2), and a medical history of pulmonary conditions (OR, 2.5; 95% CI, 1.4-4.4) were associated with increased risk of erythrocytosis in patients with hematocrit greater than 0.50 l/l.

Additionally, results indicated hematocrit levels increased most during the first year of testosterone therapy, with levels increasing from 0.39 l/l at baseline to 0.45 l/l after the first year. Investigators pointed out that there was only a slight continuation of this increase in the remainder of the follow-up period, but the risk for develop erythrocytosis continued to increase from 10% after 1 year to 38% after 10 years.

This study, “Erythrocytosis in a large cohort of trans men using testosterone: a long-term follow-up study on prevalence, determinants and exposure years,” in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism.