Article

Two Gene Therapies Fix Fault in Sickle Cell Disease and ß-thalassemia

Author(s):

Two gene therapy techniques in separate, concurrently published trials demonstrate clinical success in mitigating monogenic hemoglobinopathies.

Two different gene therapies have been used to mitigate a mechanism underlying development of sickle cell disease (SCD) and transfusion-dependent ß-thalassemia (TDT), and both have demonstrated clinical success in separate, concurrently published trials.

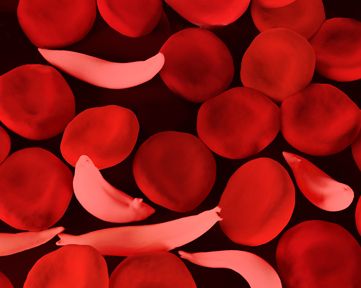

The hemoglobinopathies manifest after fetal hemoglobin synthesis is replaced by adult hemoglobin in individuals who have inherited a mutation in the hemoglobin ß subunit gene (HBB).Identifying factors in the conversion from fetal to adult hemoglobin synthesis, however, has provided potential targets for therapeutic intervention.

Gene therapy that can safely arrest or reduce the conversion offers the potential for a one-time treatment to obviate the need for lifetime transfusions and iron chelation for patients with TDT, and the pain management, transfusions and hydroxyurea administration for those with SCD.

Two groups of investigators have now reported in The New England Journal of Medicine that, using different gene therapy techniques that target the transcription factor, BCL11a, involved in the globin switching, they have improved clinical outcomes in patients with TDT and with SCD.

In an editorial in the issue featuring the 2 studies, Mark Walters, MD, Blood and Marrow Transplant Program, University of California, San Francisco-Benioff Children's Hospital, welcomed the breakthroughs.

"These trials herald a new generation of broadly applicable curative treatments for hemoglobinopathies," Walters wrote.

In one clinical trial with 2 patients, one with TDT and the other with SCD, Haydar Frangoul, MD, MS, Medical Director, Pediatric Hematology/Oncology, Sarah Cannon Center for Blood Cancer at the Children's Hospital at Tristar Centennial, and colleagues administered CRISPR-Cas9 gene edited hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) with reduced BCL11A expression in the erythroid lineage.

The product, CTX001, had been shown in preclinical study to restore γ-globulin synthesis and reactivate production of fetal hemoglobin. Both patients underwent busulfan-induced myeloablation prior to receiving the treatment.

The investigators suggested that the CRISPR-Cas9-based gene-edited product could change the paradigm for patients with these conditions, if it was found to successfully and durably graft, produce no "off-target" editing products, and, importantly, improve clinical course.

"Recently approved therapies, including luspatercept and crizanlizumab, have reduced transfusion requirements in patients with TDT and the incidence of vaso-occlusive episodes in those with SCD, respectively, but neither treatment addressed the underlying cause of the disease nor fully ameliorates disease manifestations," Frangoul and colleagues wrote.

The investigators reported that both patients had "early, substantial, and sustained increases" in pancellularly distributed fetal hemoglobin levels during the 12-month study period. Further, the patients no longer required transfusions, and the patient with SCD no longer experienced vaso-occlusive episodes after the treatment.

In commentary accompanying the report, Harry Malech, MD, Genetic Immunotherapy Section, Laboratory of Clinical Immunology and Microbiology, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease (NIAID), National Institutes of Health (NIH), Bethesda, MD, described the investigators' application of the gene-editing technology as a "remarkable level of functional correction of the disease phenotype."

"With tangible results for their patients, Frangoul et al have provided a proof of principle of the emerging clinical potential for gene-editing treatments to ameliorate the burden of human disease," Malech pronounced.

In the other published trial, with 6 patients with SCD, Erica Esrick MD, Dana-Farber/Boston Children's Cancer and Blood Disorders Center, Harvard Medical School, and colleagues described results with infusion of gene-modified cells derived from lentivirus insertion of a gene that knocks down BCL11a by encoding an erythroid-specific, inhibitory short-hairpin RNA (shRNA).

The severity of SCD that qualified patients for enrollment included history of stroke (n = 3), frequent vaso-occlusive events (n = 2) and frequent episodes of priapism (1).Patients were followed for 2 years, and offered enrollment in a 13-year long-term follow-up study.The infusion of the experimental drug BCH-BB694, from the short hairpin RNA embedded within an endogeonous micro RNA scaffold (termed a shmiR vector), was initiated after myeloablation with busulfan.

Esrick and colleagues reported that, at median follow-up of 18 months (range, 7-29), all patients had engraftment and a robust and stable HbF induction broadly distributed in red cells.Clinical manifestations of SCD were reduced or absent during the follow-up period; with no patient having a vaso-occlusive crisis, acute chest syndrome, or stoke subsequent to the gene therapy infusion.Adverse events were consistent with effects of the preparative chemotherapy.

"The field of autologous gene therapies for hemoglobinopathies is advancing rapidly," Esrick and colleagues reported, "including lentiviral trials of gene addition in which the nonsickling hemoglobin is formed from an exogenous γ-globin or modified ß-globin gene."

Walters agreed that gene therapy is rapidly progressing, but expressed concern about the large gap that looms between laboratory bench and clinical bedside, particularly for this affected population.

"Access to and delivery of these highly technical therapies in patients with sickle cell disease will be challenging and probably limited to resource-rich nations, at least in the short term," Walters commented.

The studies, “CRISPR-Cas9 Gene Editing for Sickle Cell Disease and ß-Thalassemia,” as well as, “Post-Transcriptional Genetic Silencing of BCL11A to Treat Sickle Cell Disease,” were published online in The New England Journal of Medicine.