Article

Updates in Atopic Dermatitis

Author(s):

Atopic dermatitis is the most common inflammatory pediatric skin disorder, with reported incidences ranging from 10% to 20%. The principles of effect care include fixing the skin barrier, short-circuiting inflammation, decreasing itching, treating infections, and striving for prevention by addressing the triggers.

Atopic dermatitis is the most common inflammatory pediatric skin disorder, with reported incidences ranging from 10% to 20% (urban areas are associated with higher incidence rates).

At the 2014 AAP National Conference & Exhibition, Sheila Fallon Friedlander, MD, Professor of Clinical Pediatrics & Medicine, UCSD Medical Center & Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego, CA, gave an informative talk on the assessment, diagnosis, and management of cidlren with atopic dermatitis, which she characterized as “a chronic relapsing extremely pruritic skin condition.”

The economic impact of atopic dermatitis is one measure of its seriousness, with estimates ranging from $364 million to $3.8 billion in direct and indirect costs per year. However, Friedlander wanted to draw attention to the major quality of life (QOL) issues associated with this condition, which she said are comparable to those seen in cancer and diabetes mellitus. Some of the problems, especially sleep deprivation and depression, can also afflict the caregivers of affected children.

Clinical findings in atopic dermatitis are age-dependent. With infants, the lesions start on the face, the perioral area, cheeks, scalp, and extensor muscles. For ages 1-4 years, the disease most often presents in the midline of the face, the nose excluding the nasal tip, the flexors, hands, and retroauricular fissures. In adolescent patients, the hands, feet, and head and neck are particularly affected.

If the disease is neglected or resistant to treatment, there can be marked disfigurement due to lichenification and infection. This can result in serious social difficulties for the child in addition to the clinical effects.

For a differential diagnosis, inflammatory conditions such as seborrheic dermatitis, psoriasis, and contact dermatitis need to be considered as well as infections (scabies), metabolic and immunologic disorders, histiocytosis, and T-cell lymphoma.

As part of the medical history, Friedlander recommends asking if other family members are itching. Contact dermatitis caused by a combination preservative used in baby wipes, MCI/MI, has recently been reported. Reported comorbidities include ADHD, autism, and depression; anxiety and conduct disorder are over-represented in atopic dermatitis.

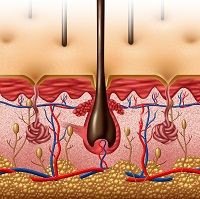

Friedlander reviewed mechanisms of causation such as structural abnormalities, genetics and immunologic and enzymatic changes. With excessive dyscohesion of surface cells, barrier dysfunction and water loss ensue.

Friedlander spent some time discussing recent findings on the roles of ceramides and the multifunctional protein filaggrin in the maintenance of cutaneous barrier function. However, the molecular mechanisms leading to dermatitis remain unclear. S. aureus colonization has been noted as a complication in atopic dermatitis but its significance is still being elucidated.

Attempts to repair or restore the functions of the epidermal barrier are a critical part of treatment of atopic dermatitis with the use of either moisturizers or barrier creams and ointments to retain water. However, some patients do not do well with petrolatum-type products due to excessive retention of water that can cause maceration and promote fungal infections. Hygiene is important but the use of harsh soaps and detergents can irritate and dry the skin and increase skin pH which can result in inappropriate activation of skin enzymes.

If infection appears to be playing a role, bleach baths should be considered not just as an antimicrobial but also as a potential anti-inflammatory agent, with possible structural effects, too. Antibiotics should be used sparingly. Wet wraps can help to reduce the itching, especially in severe cases, but take some skill in application in infants.

The current best tools for treating inflammation are topical corticosteroids and topical calcineurin inhibitors (tacrolimus and pimecrolimus). Care should be taken to select a corticosteroid with potency appropriate for the severity of the condition to minimize side effects.

For the severely afflicted patient refractory to topical treatment, the temptation to use systemic corticosteroid therapy should be resisted even if there is pressure from the parents. Oral cyclosporine should not be used for more than a year due to kidney toxicity. Phototherapy is a reasonable option if feasible.

In her closing remarks, Friedlander listed the principles of therapy for atopic dermatitis: Fix the skin barrier, short-circuit inflammation, decrease itching, treat infections, and strive for prevention by addressing the triggers. The patient or caregiver should be provided with a good understanding of the disease and be given a reasonable action plan.