Article

Viral Hepatitis Up to 10 Times More Likely in Indigenous Populations

Author(s):

Poverty and poor healthcare raise the trending global risks.

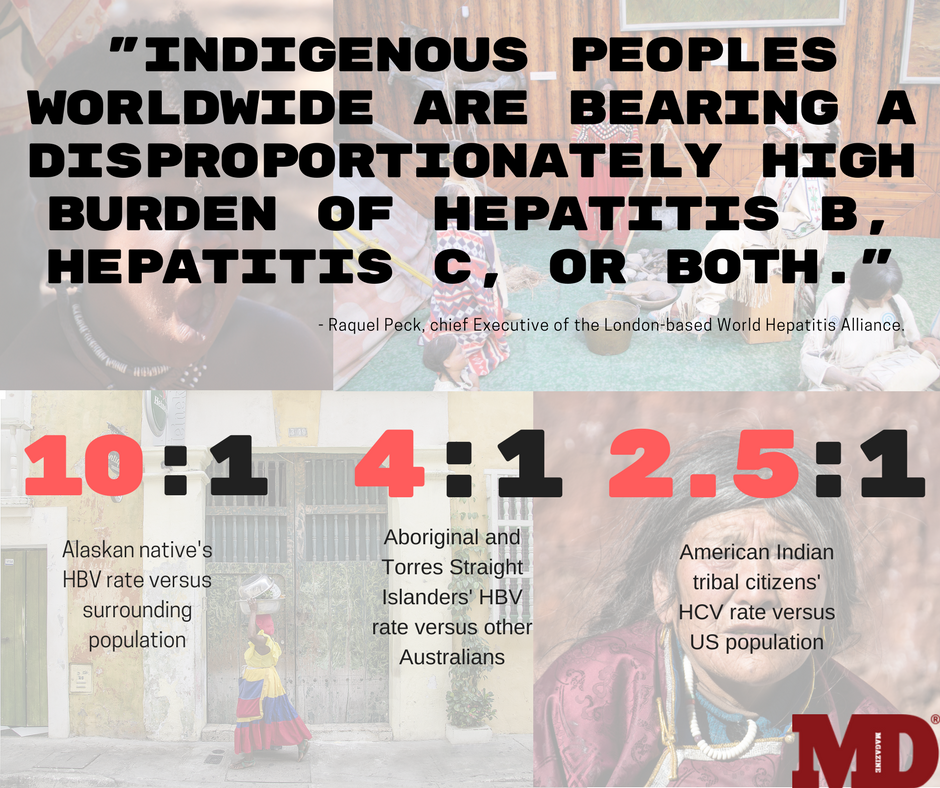

American Indian tribal citizens and other native peoples around the world are up to 10 times more likely to be infected with viral hepatitis than others in their countries, according to a global analysis of data on the liver-attacking diseases.

"Indigenous peoples worldwide are bearing a disproportionately high burden of hepatitis B, hepatitis C, or both,” said Raquel Peck, chief Executive of the London-based World Hepatitis Alliance.

Poverty, injection drug use, incarceration and the lack of healthcare and prevention all contribute to the risk to native groups, the findings show.

Researchers investigated the prevalence of hepatitis B (HBV) and hepatitis C (HCV) in North and South America, Australia and New Zealand. The HCV data covered 11 countries, 23 specific indigenous nations and 12 broader groups from 1991 onward. For HBV, 13 countries, 106 indigenous nations and 22 broader groups were reviewed.

Alaska’s native population showed the greatest overall impact. Their HBV rates were 10 times higher than levels in the surrounding communities. However, the state’s universal HBV vaccination program has almost eliminated new infections among youth and has likely reduced the overall HBV prevalence in recent years, researchers said.

“This proves that vaccination in the indigenous population can have a very large impact on the disease burden,” said Homie Razavi, PhD, MBA and Managing Director of the CDA Foundation. The findings will be submitted for publication in The Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology.

Razavi, who presented at the World Indigenous Peoples' Conference on Viral Hepatitis in Anchorage on August 8 and 9, said the fact that HBV hasn’t been eliminated worldwide represents a failure of global health institutions. The HBV vaccine is effective in preventing mother to child transmission and anti-viral treatment reduces viral load and person to person transmission, he said.

“Both tools have been around since the 1990s yet we still have a high infection rate,” he said.

HCV infection was greatest among Australian and Canadian native peoples. Australia’s aboriginal citizens and islanders from the Torres Strait had HCV rates 3 times greater than in the general population, as did Canada’s Inuit and Métis First Nations peoples.

In a bright spot in the US, the Cherokee Nation is aggressively targeting HCV among its American Indian tribal citizens with intent to wipe out the virus.

“The indigenous populations in nearly all countries have a lower income than the general population,” Razavi said. “The Cherokee Nation used this to their advantage.”

Half of the patients treated are on Medicaid and the other half receive their drugs free through Gilead Sciences Inc.’s Patient Assistance program, Razavi said.

“The Cherokee Nation only pays for screening but pays almost nothing for HCV treatment,” he explained. “This was a brilliant strategy that can be used by other native American Nations in the US to provide access/cure to their population.”

So far, almost half of individuals age 20 to 69 who live within tribal boundaries in Oklahoma have been screened. About a quarter of those thought to be infected have been cured, said Jorge Mera, MD, Head of Infectious Diseases at Cherokee Nation in Tahlequah, OK.

Razavi stressed that expanding native peoples’ access to viral hepatitis care is crucial.

“Hepatitis B and hepatitis C are cancer causing viruses,” Razavi said, noting that treatment would reduce liver cancer deaths from the viruses. “We have already seen a reduction in the number of liver transplants (in the general population) required due to expanded HCV treatment. We should see the same among the indigenous populations if access is expanded.”

A press release regarding the study was made available.

Related Coverage

Triple Drug Regimen Succeeds Against Treatment-Resistant HCV

2 Commerce Drive

Cranbury, NJ 08512

All rights reserved.