Article

What’s next for rheumatoid arthritis-associated periodontal disease?

Author(s):

Identifying and treating symptoms that can appear years before the clinical onset of rheumatoid arthritis could play a role in helping patients offset the condition. And now, new research that identifies a bacteria as a potential cause of these symptoms has one rheumatologist positing whether improved oral care, or maybe a vaccine, might be effective in preventing rheumatoid arthritis.

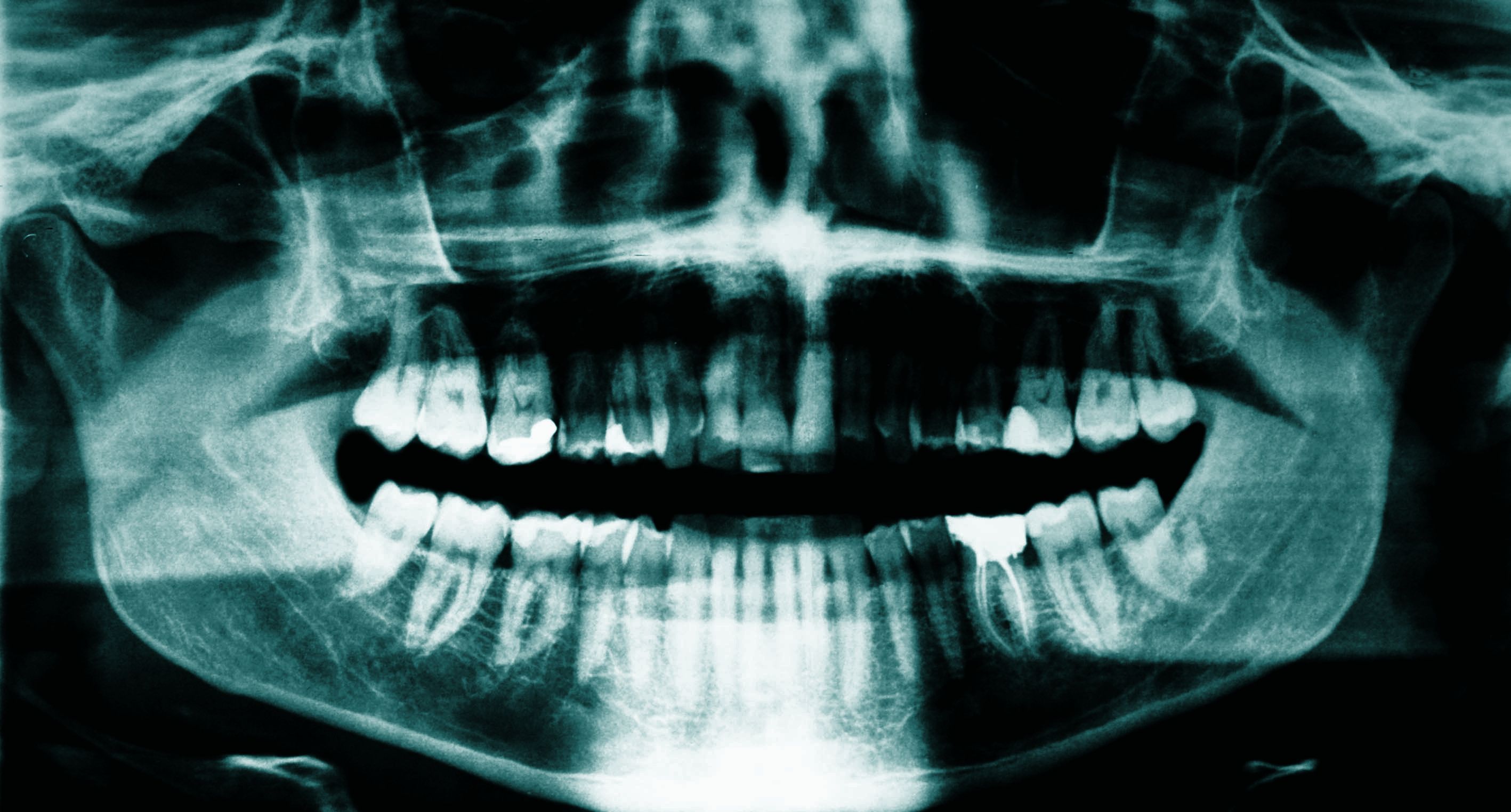

(©LaurentDambies,AdobeStock.com)

Identifying and treating symptoms that can appear years before the clinical onset of rheumatoid arthritis could play a role in helping patients offset the condition. And now, new research that identifies a bacteria as a potential cause of these symptoms has one rheumatologist positing whether improved oral care, or maybe a vaccine, might be effective in preventing rheumatoid arthritis.

Targeting periodontal disease in patients before rheumatoid arthritis symptoms appear could improve outcomes, said Hubert Marotte, M.D., Ph.D., a rheumatologist with the University Hospital Saint-Etienne in France. He is the author of an invited commentary that was published in the June 7 issue of JAMA Network Open in response to a study by Kulveer Mankia, et al. on the connection between periodontal disease and rheumatoid arthritis.

The opportunity for intervention can present itself up to 10 years before the onset of clinical rheumatoid arthritis, he wrote.

“This could be the next huge challenge after the window of opportunity and the treat-to-target strategy, which revolutionized the management and the outcome of rheumatoid arthritis in the past 20 years,” he wrote. “The next steps should be exploring ways to prevent rheumatoid arthritis onset in a subgroup of people with high-risk rheumatoid arthritis.”

The link between periodontal disease, a condition marked by the loss of tooth-supporting tissue, and rheumatoid arthritis is known, as both conditions share genetic and environmental factors. It is also known that the development of anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (anti-CCP) years before the onset of rheumatoid arthritis is a hallmark characteristic of the condition. Additionally, existing data reveals the risk of rheumatoid arthritis increases with more severe cases of periodontal disease, with 10 percent of cases considered severe.

But, while this connection is identified, little has been unearthed, to-date, about what supports it.

Recent findings point to two bacteria present in the oral microbiome-Porphyromonas gingivalis (P. gingivalis) and Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans. The thought, Dr. Marotte wrote, is that severe periodontal disease produces an excess of citrullinated protein, causing a break of tolerance with anti-CCP induction. Both are known to induct citrullinated proteins. Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans induces citrullination in neutrophils by neutrophil extracellular trap activation and release through leukotoxin A.

But, it is P. gingivalis, which has a specific deiminase enzyme, that could be most responsible.

According to a new study published in JAMA Network Open, P gingivalis is found in increased levels in patients who are both at-risk for developing rheumatoid arthritis and those who already have early-stage rheumatoid arthritis when compared to healthy individuals.

In fact, he says, a rat model study published earlier this year in the Annals of Rheumatic Diseases demonstrated that P. gingivalis plays a specific role in rheumatoid arthritis. After periodontal disease developed, researchers observed several factors that mirrored the preclinical phase of rheumatoid arthritis. The rats presented immunologic abnormalities, including anti-CCP, high interleukin 17A, and the chemokine CXCL 1 in their blood.

If further research confirms the findings already published in literature, he says, it will be critical to address periodontal disease as early as its first identification, perhaps when it is associated with anti-CCP in preclinical rheumatoid arthritis. Improved oral care worldwide or possible vaccination are potential treatment options. Targeting periodontal disease in patients who already have mature rheumatoid arthritis or, after the effects of anti-CCP have occurred, is too late to make any changes for the individual.

It’s possible, he suggests, that because the conditions are linked, their existing treatments could be interchangeable. For example, rituximab and tocilizumab, two medications used to treat rheumatoid arthritis, also reduce the gingival inflammation and gingival bone destruction found with periodontal disease. However, infliximab augments gingival inflammation while preventing gingival bone loss. No periodontal disease treatment, such as full-mouth nonsurgical scaling and root planning, has been effective as a therapy for established rheumatoid arthritis.

Addressing periodontal disease could also have potential downstream effects impacting additional associated diseases.

“Preventing periodontal disease could also prevent a spectrum of systemic diseases associated with periodontal disease, including Alzheimer disease,” he wrote.

REFERENCE

Hubert Marotte, MD, PhD. "Determining the Right Time for the Right Treatment-Application to Preclinical Rheumatoid Arthritis."JAMA Network Open. June 7, 2019. DOI:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.5358