Article

Why Do Some People Get HIV After Exposure But Others Don't?

Author(s):

Some HIV-1 strains are able to get past the body's natural barriers better.

Unprotected sexual exposure to the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) doesn’t necessary lead to infection. In fact, some studies have gone as far as to saying that successful HIV-1 transmission occurs only one out of 1,000 times.

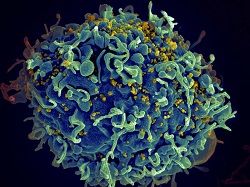

HIV doesn’t have it easy when trying to establish a new infection. Between genital mucosa, tightly packed epithelial cells, and initial immune responses, there are a number of innate barriers to overcome. But even still, thousands of new infections occur in the United States every year.

As Beatrice Hahn, MD, asked, “What is unique about these transmitted viruses that make it this far?” That’s what she, along with colleagues at the University of Pennsylvania set out to understand.

The researchers examined blood and genital secretions from four donors with HIV-1 fully suppressed by antiretroviral therapy (ART) and their matched recipients. They were able to generate 300 virus isolates from individual HIV-1 particles and identify characteristics of the virus strains. This allowed the team to see how the virus got around the genital mucosa, which is meant to block intruders.

It turns out that there’s a sub-population of HIV-1 strains that are naturally predisposed to better establish new infections.

Viruses isolated from the recipients were three times more infectious and able to replicated 1.4 higher than those gathered from the donors. In addition, these viruses were much more resistant to two type 1 interferons, IFN-beta and IFN-alpha2—requiring eight-fold and 39-fold higher concentrations, respectively, in order to reduce replication by 50%.

“Knowing the viral properties that confer the ability to transmit despite all of the human body’s barriers to infection, might aid the development of vaccines against HIV-1,” said Hahn, a professor of Medicine and Microbiology in the Perelman School of Medicine at Penn.

Furthermore, the viruses from the recipients were released from infected CD4 immune cells. This indicates that cell free particle production is key in HIV-1 transmission, the researchers explained.

“This means that rapidly multiplying strains of HIV-1 that are interferon resistant have an increased transmission fitness,” said co-first author, Shilpa Iyer, a doctoral student in the Han lab.

A final piece of this research suggests that a virus is less likely to replicate properly with larger clones of proviral sequences.

“But we still don’t know which viral gene products render HIV-1 resistant to interferon and how they function. The next steps will be to dissect these mechanisms to define possible new targets for AIDS prevention and therapy,” Hahn concluded.

The study, “Paired quantitative and qualitative assessment of the replication-competent HIV-1 reservoir and comparison with integrated proviral DNA,” was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. The news release and side photo was provided by the University of Pennsylvania.

Related Coverage:

Researchers Challenge CDC’s HIV Prevention Guidelines

HIV Structural Discoveries Could Lead to Advanced Treatments

Officials Investigate HIV Transmission Risk Via Cosmetic Skin Treatment