Article

Zika More Dangerous than Thought: Brain Damage Risk Seen in All Infections

Author(s):

Infants exposed to Zika virus in-utero aren't the only ones at risk of brain damage from the virus. Researchers at The Rockefeller University and La Jolla Institute for Allergy and Immunology believe the virus can "wreak havoc" in almost anyone's brain.

Zika infection could put adults at risk of dementia and other neurological diseases and is likely even more dangerous than first thought, researchers at The Rockefeller University and La Jolla Institute for Allergy and Immunology report.

Based on a mouse study, they believe the virus could get into almost anyone’s brain—not just those of developing fetuses.

“Zika can clearly enter the brain of adults and can wreak havoc,” says Sujan Shresta, PhD, a professor at La Jolla.

Certain adult brain cells may be vulnerable to infection, including neural progenitor cells, also known as the stem cells of the brain.

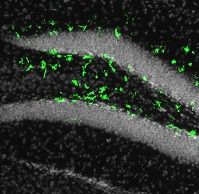

In the slide pictured, illumination of the fluorescent biomarker in green showed the adult mouse brain could be infected by Zika in the subgranular zone of the hippocampus (Photo by Laboratory of Pediatric Brain Disease at The Rockefeller University and Cell Stem Cell).

Shresta and colleagues published their findings today in Cell Stem Cell.

The virus has already been associated with an increase in microcephaly in infants born to infected mothers. It can also cause , as well as shown to cause Guillain-Barre Syndrome, a rare illness in which the immune system attacks parts of the nervous system resulting in muscle weakness or even paralysis.

Since that syndrome usually develops after the infection has cleared, Shresta says, “We propose that infection of adult neural progenitor cells could be the mechanism behind this," she added.

Using mice, the researchers have shown that the virus was able to get into pockets of the rodents’ brains where these progenitor cells are located. Those are the subventricular zone of the anterior forebrain and the subgranular zone of the hippocampus, both vital for learning and memory.

According to Joseph Gleeson, MD, head of the Laboratory of Pediatric Brain Disease and an adjunct professor at The Rockefeller University in New York City, in a mouse model engineered by Shresta “It was very clear that the virus wasn’t affecting the whole brain evenly, like people are seeing in the fetus.” He added “In the adult, it’s only these two populations that are very specific to the stem cells that are affected by the virus,” cells that are “somehow very susceptible to the infection.”

The infection correlated with evidence of cell death and reduced generation of new neurons in these regions, which could set the stage for cognitive decline, depression, Alzheimer’s, or other neuropathological ailments.

The team added that some people may mount an effective immune response and halt the virus, but others, particularly those with weakened immune systems, may not.