Publication

Article

Hemophilia Reports

2012 Treatment Guidelines for Rheumatoid Arthritis: An Update from the American College of Rheumatology

During the past decade, changes in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) have been accumulating faster than treatment experience can be evaluated.

D

uring the past decade, changes in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) have been accumulating faster than treatment experience can be evaluated. Consequently, the 2012 guideline revisions from the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) follow just four years after the previous version in 2008. The update is welcomed by clinicians, who must manage patients taking a range of different agents, choose treatment regimens based on tolerability and efficacy in each individual patient, and fit treatments to particular points in the progression of the disease.

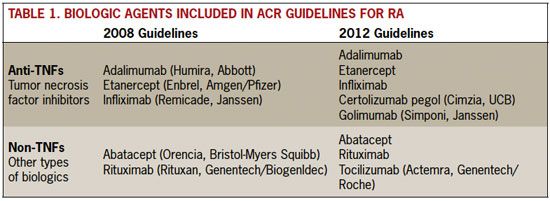

Most of the changes in the 2012 revision reflect treatment lessons learned as biologic response modifier therapies have become better known (Table 1). A total of eight biologic agents were reviewed for the 2012 revision. In 2008, only five biologics were available for review: two nontumor necrosis factor (non-TNF) drugs, abatacept (a selective co-stimulation modulator) and rituximab (a B-cell inhibitor), as well as three anti-TNF drugs, adalimumab, etanercept, and infliximab.

The 2012 guidelines added another non- TNF biologic, tocilizumab (which blocks the IL-6 messenger cytokine), and two additional anti-TNFs, certolizumab pegol and golimumab. The particular nomenclature separating these biologics—anti-TNFs and non-TNFs—is that used by the ACR, but both mechanisms of action are effective in halting RA disease progression. Clinicians are able to select one or another of the drugs based on tolerability and effectiveness in individual patients.

Table 1. Biologic Agents Included in ACR Guidelines for RA

Agents

Rollover to enlarge.

Anti-TNFs and Non-TNFs

Tumor necrosis factor is a proinflammatory cytokine produced by the immune system. Excess levels of TNF are associated with inflammatory diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, plaque psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, and ankylosing spondylitis. The anti- TNFs reduce TNF to control inflammation. Non- TNFs use other mechanisms to interrupt the inflammatory autoimmune response. Because both anti-TNF and non-TNF agents affect the immune response, they raise the risk of infection for patients taking them.

The anti-TNFs are the most familiar of the biologics, and the class has been used for more than 10 years to treat inflammatory conditions. Given by injection or infusion, these drugs are able to stop disease progression. Often, anti-TNFs as well as non-TNFs are used in combination with earlier disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) to increase their potency, most often with methotrexate.

The 2012 guidelines focus on use of both DMARDs and biologics, making recommendations regarding selection of and switches between these agents. New recommendations favor early initiation of treatment (within the first 6 months following diagnosis) using triple-combination DMARD regimens or a biologic, with or without methotrexate, for patients who show high disease activity with poor prognosis. Biologics are not recommended for early RA in patients with lowto- moderate-disease activity and without poor prognosis.

Use of biologics as first-line therapy (in some patients) and beginning such treatment in early RA constitute two changes from the 2008 guidelines and probably better reflect existing practice patterns that changed as biologics became better understood.

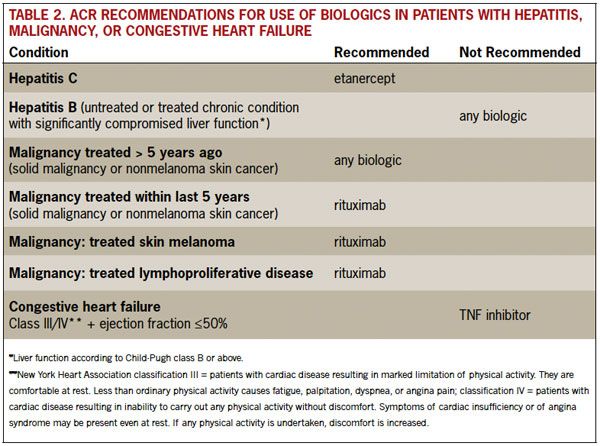

An important addition in the 2012 revision is an update focused on safety issues that have become more apparent over time. The ACR makes new recommendations for use of biologic agents in high-risk patients, including patients who have hepatitis, congestive heart failure, or a history of malignancy, and are thus considered most at risk for infection. Table 2 shows recommended biologic agents for treatment of patients at risk.

In addition, screening for tuberculosis is recommended for all patients who are beginning or currently receiving biologic agents. Vaccinations are recommended for all patients taking DMARDs or biologic agents: pneumococcal, influenza, hepatitis B, human papillomavirus (HPV), and herpes zoster.

Table 2. ACR Recommendations for Use of Biologics in Patients With Hepatitis, Malignancy, or Congestive Heart Failure

Recommendations

Rollover to enlarge.

Other New Practice Resources from ACR

Osteoarthritis

In April 2012, the ACR released updated osteoarthritis (OA) guidelines. These were published in the April issue of Arthritis Care & Research and are on the website (www. rheumatology.org) for easy downloading. The OA guidelines address pharmaceutical as well as nonpharmaceutical treatments for the hand, hip, and knee.

Lupus

In June 2012, the ACR released updated guidelines for treatment of lupus nephritis. These guidelines were published in the June issue of Arthritis Care & Research and are available on the ACR website.

Registry

The ACR maintains the ACR Rheumatology Clinical Registry. The registry is a free, easyto- use, Web-based tool developed to assist members in practice. It is also available as an application for handheld devices. The registry delivers information based on local population management; it is integrated with national qualitycare programs and contains quality measures aimed at improving care and drug safety for patients with rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis, osteoporosis, gout, and juvenile idiopathic arthritis.

In 2011, the registry enabled electronic submission and retrieval capabilities to support exchange of information with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS) and the Electronic Prescribing Incentive Program (eRx). More details about the registry are available on the ACR website.

Source:

Singh JA, Furst DE, Bharat A, et al. 2012 Update of the 2008 American College of Rheumatology Recommendations for the Use of Disease-Modifying Antirheumatic Drugs and Biologic Agents in the Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Arthritis Care & Research. 2012;64(5):625-639.

American College of Rheumatology website. Available at http://www.rheumatology.org. Accessed June 21, 2012.