Article

Activity Monitor Usage in Patients Requiring Total Knee Replacements

Author(s):

Despite the benefits of physical activity, participation is low, both within the general population and among individuals with osteoarthritis (OA). Activity monitors may aid in increasing these levels in patients with OA as well as in those requiring a total knee replacement.

Most total knee replacement (TKR) recipients recognized the importance of physical activity (PA) and were willing to use activity monitors to increase activity levels after surgery, motivated by both external and internal factors, according to a study published in Rheumatology.1

“PA offers many health benefits, including prevention and management of chronic disease, delay of functional decline and disability onset, and improved quality of life (QoL),” investigators stated. “Despite these benefits, participation in PA is low, both within the general population and among individuals with osteoarthritis (OA).”

In this qualitative study, patients were recruited from the Orthopedic and Arthritis Center at Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH) using electronic medical records. Investigators narrowed the search to include patients who either had a TKR scheduled within the next 6 weeks or recently underwent surgery.

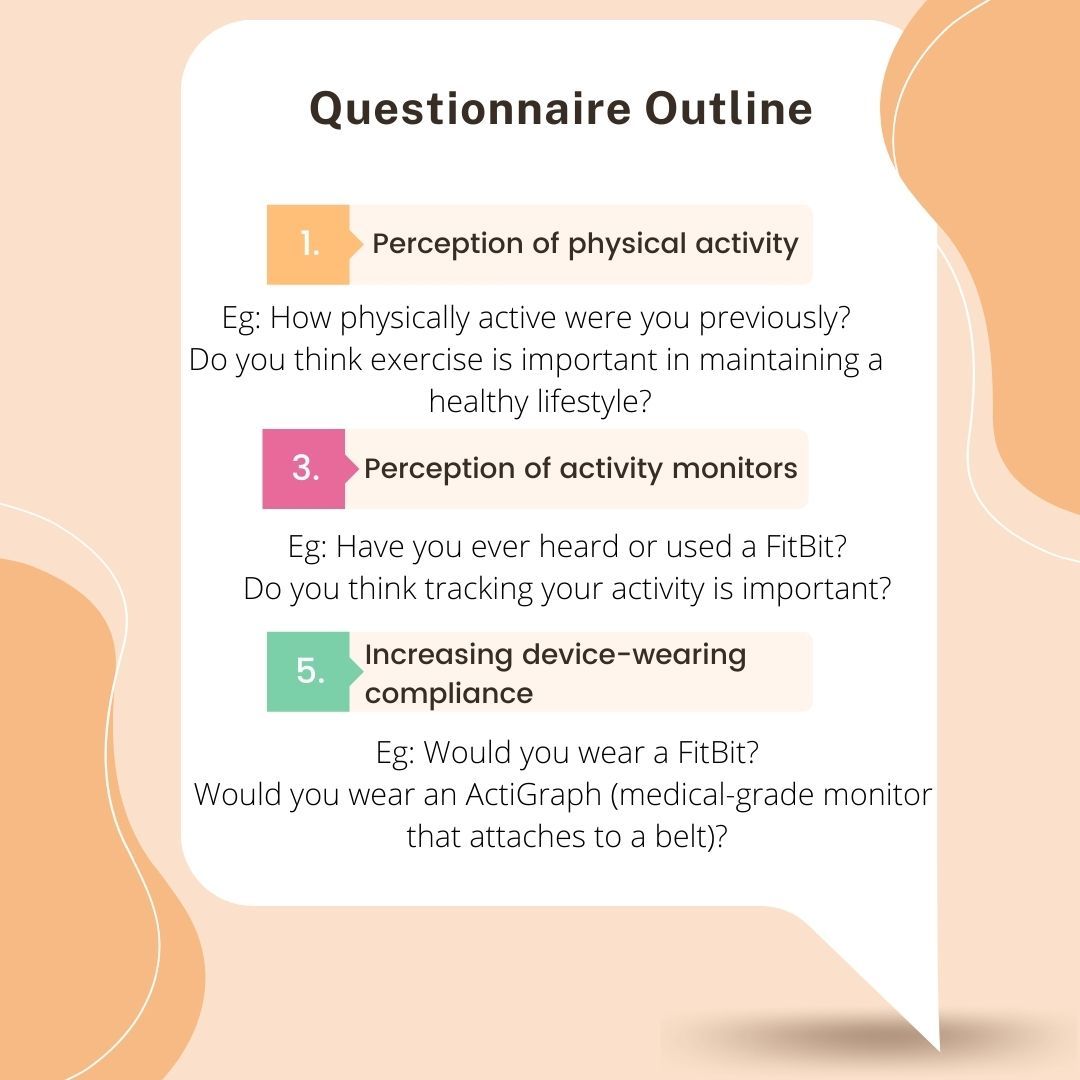

A survey was designed to determine the role of PA in their daily lives and to identify factors that would motivate or deter them from wearing activity monitors and engaging in regular PA. Identifying these goals may help rheumatologists create strategies to increase activity levels among their patients.

After eligibility assessments, 27 participants were included in the study. Ten of the patients were interviewed pre-surgery and 17 were interviewed afterwards. The mean age was 66 years, 89% were white, and the majority of patients were women (16 vs 11, respectively).

In the second phase of the study, 3 co-authors determined patterns and themes from the responses and created a thematic map to illustrate the relationship between themes.

In total, 9 themes were identified:

1: Exercise benefits both physical and mental health

Patients reported exercise and diet are necessary tools to improve physical health, aid in weight loss, and maintain good mental health.

2: Pain and limited function hinders daily life

The ability to socialize, pursue hobbies, climb-stairs, clean, and shop were impacted by their physical limitations.

3: TKR is an opportunity to increase QoL

Participants believed that the surgery would enable them to resume activities they valued.

4: Situational factors impact levels of PA

Examples of situational factors included the COVID-19 pandemic, weather, amount of free time, and other health factors.

5: Friends and family encourage use of activity monitors

Those with more active friends and family were more likely to become more physically active. Additionally, less tech-savvy participants were more willing to use a monitor when they had someone who could help set it up for them.

6: Prior activity levels influence post-surgery goals

Most patients wanted to achieve or exceed pre-development of advanced OA activity levels.

7: Activity monitors motivate patients to achieve and set goals

Patients reported that tracking steps promotes physical activity.

8: Different incentives work for different individuals

Some of the factors included financial, pleasing their rheumatologist, self-motivation, and reminders.

9: Participants had a generally favorable perception of activity monitors and activity tracking

Tracking PA metrics would help them successfully recover as well as monitor and increase PA levels.

A limitation of the study was the lack of objective data to determine PA levels. Generalizability may be reduced as all patients came from a single medical center. Further, participants were not asked about environmental or systemic barriers to exercise.

“Individuals who undergo TKR are motivated in large part by an inability to engage in valued activities because of knee pain and impaired function,” investigators concluded. “Future research should investigate whether providing patients with activity monitors before and after surgery could help them set realistic goals, monitor their progress, and increase their PA levels. Lastly, clinicians and researchers may consider personalizing interventions, including the type of PA monitor, based on patient preferences, goals, and values.”

Reference:

Arant KR, Zimmerman ZE, Bensen GP, Losina E, Katz JN. Perceptions of Physical Activity and the Use of Activity Monitors to Increase Activity Levels in Patients Undergoing Total Knee Replacement [published online ahead of print, 2021 Aug 19]. ACR Open Rheumatol. 2021;10.1002/acr2.11324. doi:10.1002/acr2.11324