Publication

Article

Cardiology Review® Online

Chlorthalidone Versus Hydrochlorothiazide for Hypertension in Older Adults

Harry E. Davis II , MD, FACP

Review

Dhalla IA, Gomes T, Yao Z, et al. Chlorthalidone versus hydrochlorothiazide for the treatment of hypertension in older adults. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:447- 455.

The use of thiazide diuretics for the treatment of hypertension is strongly encouraged by current guidelines.1 Although hydrochlorothiazide is more commonly prescribed in North America,2 recent reviews have suggested that chlorthalidone may be a better choice. In fact, Kostis el al suggested that use of chlorthalidone was associated with an increase in survival free of cardiovascular death and a reduction in all-cause mortality.3

Study Design

Given the lack of a large, randomized, controlled trial comparing these 2 widely used drugs, Dhalla et al conducted a retrospective population- based cohort study of residents of Ontario, Canada, who were over 65 years of age.4 They used linked health care databases to construct a cohort of patients newly treated with either drug during the period January 1, 1993 to March 31, 2010. The researchers excluded patients who had been hospitalized for myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, or heart failure (HF) within the past year to focus on patients treated for uncomplicated hypertension. Patients were followed for a maximum of 5 years. The study’s primary outcome was a composite of death or hospitalization with acute MI, HF, or ischemic stroke. The investigators also considered safety outcomes by examining hospitalization with hypokalemia or hyponatremia and all-cause hospitalization. The study was funded by a grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care; no industry funding was reported.

The final cohort included 10,384 patients in the chlorthalidone group and 19,489 in the hydrochlorothiazide group. Data were analyzed for patients prescribed 12.5 mg, 25 mg, or 50 mg of chlorthalidone per day and 12.5 mg, 25 mg, or 50 mg of hydrochlorothiazide per day. The mean starting doses were 27.3 mg for chlorthalidone and 18.3 mg for hydrochlorothiazide. It should be noted that the percentages of patients initially prescribed 12.5 mg, 25 mg, and 50 mg of chlorthalidone per day were 11%, 70%, and 10%, respectively. For hydrochlorothiazide the initial dose breakdown was 67%, 24%, and 5% for the 12.5-mg, 25-mg, and 50-mg doses.

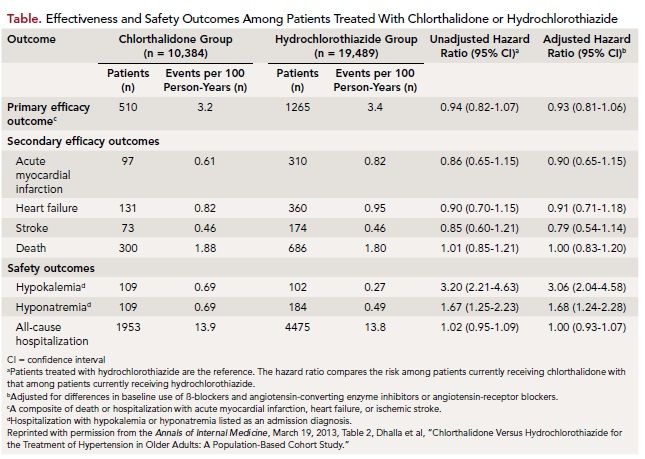

The composite primary outcome of death or hospitalization with MI, HF, or stroke was seen in 510 chlorthalidone patients and 1265 hydrochlorothiazide patients. After adjusting for baseline differences, the risk for the primary outcome with chlorthalidone was not found to be significantly lower (adjusted hazard ratio [HR], 0.93; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.81-1.06). The safety outcome analysis revealed hospitalization with hypokalemia was seen at a rate of 0.69 events per 100 person-years of follow-up in the chlorthalidone group and 0.27 events per 100 person-years in the hydrochlorothiazide group (adjusted HR, 3.06; CI, 2.04-4.58). Hospitalization with hyponatremia was seen at a rate of 0.69 events per 100 person-years of follow-up for chlorthalidone and 0.49 events per 100 person-years for the hydrochlorothiazide group (adjusted HR, 1.67; CI, 1.24-2.28).

In summary, Dhalla et al found no difference between chlorthalidone and hydrochlorothiazide with respect to stroke, MI, HF, or death in the large population-based cohort study from Ontario (Table). They did find chlorthalidone therapy was approximately 3 times more likely to be associated with hospitalization for hypokalemia and 1.7 times more likely to be associated with hospitalization for hyponatremia than with hydrochlorothiazide therapy.

The researchers acknowledged study limitations including the increased likelihood that patients treated with hydrochlorothiazide would more likely to also be treated with an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor or angiotensin-receptor blocker (ARB). They also admit that despite the large number of patients in the study, they were “unable to exclude a clinically important relative reduction in the risk for death or hospitalization with myocardial infarction, heart failure, or stroke associated with chlorthalidone.” Despite this, they concluded that hydrochlorothiazide is safer than chlorthalidone in elderly patients at typically prescribed doses.

CommentaryChoosing Between Hydrochlorothiazide and Chlorthalidone

Dhalla et al have provided a large population-based cohort study in an effort to compare the results of treating hypertension in the elderly with chlorthalidone versus hydrochlorothiazide. Their conclusion that hydrochlorothiazide is a safer drug than chlorthalidone in elderly patients seems valid with respect to the data that they have analyzed. However, several concerns may arise on review of those data. Although their approach using propensity score matching resulted in an equal distribution of several of the baseline characteristics, the concomitant medication use data remains a possible source of error. For example, the use of oral antihyperglycemic medications was less in the chlorthalidone group, yet a breakdown as to the type of antihyperglycemic medications is not shown. Due to an increased rate of cardiovascular disease in diabetics taking sulfonylureas as opposed to metformin, such data could be significant.5,6 The significantly increased use of ACE inhibitors or ARBs in the hydrochlorothiazide group, due to their association with increased levels of potassium, could have been a factor in the reduced frequency of hypokalemia in that group. In addition, it should be noted that the concomitant use of potassium-sparing diuretics was very low in both groups.

In their review of the literature regarding the relative potency of the 2 drugs, Dhalla et al note that chlorthalidone has been shown to be a more potent and longer-lasting antihypertensive medication than hydrochlorothiazide at the most frequently prescribed doses, but it also reduces serum potassium level to a greater extent. Yet their data show that this more potent drug was given in higher doses with mean treatment initiation doses of 27.3 mg for chlorthalidone and 18.3 mg for hydrochlorothiazide. Only 11% of the chlorthalidone group was started with the lower, and presumably safer, 12.5-mg dose; yet 67% of the hydrochlorothiazide group was started at this dose. The greater potassium-losing effect of chlorthalidone appears to be associated with its greater therapeutic effect. However, the smaller doses, which may also be quite effective clinically with less potassium loss, were used much less frequently.

Finally, it may be that one of the more important lessons to be learned from this excellent study is that current physician practices, at least in Ontario, do not reflect an obvious concern for the potential loss of potassium with thiazide diuretics nor an appreciation of the potential for improving cardiac function and conserving potassium levels using long-term aldosterone receptor blockade.7 It does provide a basis for questioning whether improved cardiovascular outcomes and reduced hypokalemia might be obtained by more conservative doses of the thiazide diuretics coupled with the use of long-term aldosterone receptor blockade. In conclusion, while this study has emphasized the risk of potassium loss with thiazide diuretics, it also raises the question as to the potential for improved cardiovascular outcomes with chlorthalidone if more conservative dosing were coupled with potassiumconserving measures. Thus, for now, the choice of chlorthalidone over hydrochlorothiazide may still be clinically reasonable.

References

1. Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, el al. The seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA. 2003;289:2560-2572.

2. Ernst ME, Lund BC. Renewed interest in chlorthalidone: evidence from the Veterans Health Administration. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2010;12:927-934.

3. SHEP Cooperative Research Group. Prevention of stroke by antihypertensive drug treatment in older persons with isolated systolic hypertension: final results of the Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program (SHEP). JAMA.1991;265:3255-3264.

4. Dhalla IA, Gomes T, Yao Z, et al. Chlorthalidone versus hydrochlorothiazide for the treatment of hypertension in older adults. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:447-455.

5. UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. Effect of intensive blood-glucose control with metformin on complications in overweight patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 34). Lancet. 1998;352:854-865.

6. Roumie CL, Hung AM, Greevy RA, et al. Comparative effectiveness of sulfonylurea and metformin monotherapy on cardiovascular events in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Ann Intern Med. 2012;159:601-610.

7. Edelmann F, Wachter R, Schmidt AG, et al. Effect of spironolactone on diastolic function and exercise capacity in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: the Aldo-DHF randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2013;309:781-791.

About the Author

Harry E. Davis II, MD, FACP, is Associate Professor of Medicine and Vice Chair for Education in the Department of Internal Medicine, Texas Tech University Medical Sciences Center, El Paso, TX. Dr. Davis received his medical degree from West Virginia University in Morgantown, WV, and did his internal medicine residency at Philadelphia General Hospital in Philadelphia, PA, and Letterman Army Medical Center in San Francisco, CA. He has practiced medicine with the US Army in many capacities, including Chief of Emergency Medicine in Fort Lewis, WA, Division Surgeon in the 1st Infantry Division, Fort Riley, KS, and as Commander of the Field Hospital/ Chief Medical Officer with the UN Forces in Port-au-Prince, Haiti. Dr. Davis has received numerous honors and awards for service and teaching.