Publication

Article

MDNG Neurology

Does Blue-Green Algae Cause ALS? Paul Cox, PhD, Is on a Global Quest

Author(s):

From cycad roots, to cycad seeds, to flying foxes, to human brains. Ethnobotanist Paul Cox, PhD, is traveling the world, compiling evidence that cyanobacteria, even as it is sold as a health food, can cause ALS and other neurological diseases. Gulf War veterans may have been exposed as well.

If there were a science prize for choosing the most beautiful spots to do fieldwork ethnobotanist Paul Cox, PhD, (photo) would be a contender. His research has taken him to Hawaii, Samoa, and Guam. Even home base is in a postcard setting, a laboratory in Jackson Hole, WY.

Fittingly, even the organism Cox studies sounds pretty: blue-green algae.

But it is a pretty poison, Cox has shown.

He believes exposure to this ancient and ubiquitous bacteria is involved in many clusters of ALS around the world and may also contribute to other neurodegenerative diseases including Alzheimer’s—even as blue-green algae is being sold in health food stores as a dietary supplement.

“Chronic dietary exposure to BMAA [a toxin in blue-green algae] results in the formation of neurofibrillary tangles and beta-amyloid deposits in a clear dose relationship,” Cox writes in his most recent study, published in the Proceedings of the Royal Society in January, 2016.

Not everyone is convinced that this is a key finding in the search for causes of ALS, and other scientists are urging caution in interpreting the results of his studies, but Cox and colleagues believe they are in hot pursuit of an overlooked environmental toxin.

Adding to their excitement, in the course of figuring out how BMAA affects the brain, they also believe they have found an antidote that blocks the toxin’s disastrous effects.

The story begins with research done on the South Pacific island of Guam.

Since the 1950s scientists have been puzzled by a high prevalence of an ALS-like disease among the Chamarro people, the island’s indigenous residents.

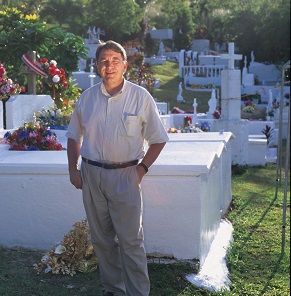

About a quarter of the Chamarro islanders die of a paralytic neurodegenerative disease, illnesses that start with symptoms of ALS and Parkinson’s dementia. On autopsy, their histopathology shows neurofibrillary tangles similar to those of Alzheimer’s disease.[Photo; Cox in Guam visiting a Chamarro cemetery]

Originally, scientists thought the ailment was likely hereditary. But they noted that outsiders who adopted a Chamorro lifestyle also came down with the symptoms.

Cox, building on the work of others, showed that the culprit is blue-green algae.

His most recent findings on the toxic effects of cyanobacteria were published in a study “Dietary exposure to an environmental toxin triggers neurofibrillary tangles and amyloid deposits in the brain,” in the Proceedings of the Royal Society in January, 2016.

Scientists studying the Chamorro people had already suspected that consuming cycad seeds, the fruit of a tropical plant, was related to the dementia that afflicted the islanders.

BMAA (beta-methylamino-L-alanine) is a non-protein amino acid. At least in people who are genetically susceptible, BMAA mimics the amino acid L-serine and inserts itself into neuroproteins, causing them to misfold and tangle, Cox says.

Cyanobacteria live in the roots of cycads and the BMAA the bacteria produce accumulates in the gametophytes of cycad seeds, Cox explains.

One study on the Guam illness had shown that macaque monkeys fed the cycad seeds also developed extreme neurological symptoms similar to those of the afflicted islanders.

The islanders regularly ate cycad seed flour made into tortillas or added to stews as a thickener.

But the theory that cycad consumption was responsible for the human illness was discounted when it was determined that for people to eat enough cycad seed flour to get an equivalent dose to what the macaques were fed in the experiment would be nearly impossible.

Then an important second discovery showed that the BMAA toxin binds to proteins. The implication was that the doses Chamarro islanders were consuming by eating cycad seeds had been underestimated.

Suspicion that BMAA found in the seeds was the culprit in the ALS-like symptoms grew even stronger when the role of flying foxes in the food chain came to light.(Photo right: flying foxes and cycad seeds.)

These creatures, along with other rodents and pigs, also eat cycad seed. But in the flying foxes the BMAA toxin is biomagnified up to 10,000 times, Cox showed in a study published in 2003. That meant that since the bats were a highly sought delicacy to Chamarro islanders, their important place on the menu was adding far more BMAA to the islander diet.

The final link between BMAA and neurological damage came when Cox and colleagues sought to prove one of Koch’s postulates: in this case that chronic exposure to the suspected toxin would cause healthy creatures to develop the neurodegenerative disease symptoms, and that the toxin could later be re-isolated from these subjects.

Using vervets, small black-faced monkeys, as their subjects, Cox and colleagues at an animal research lab in St. Kitts, West Indies, showed that when chronically exposed to BMAA in their diets the vervets developed neurofibrillary tangles and amyloid plaque, hallmarks of dementia, Alzheimer’s and to some extent, ALS.

Cox’s discovery of the workings of BMAA has also led to a potential treatment. He believes the antidote to the neurotoxin is to give the brain more L-serine.

In his research with the vervets, a group of the monkeys given L-serine along with a diet spiked with BMAA did better than those vervets that did not get L-serine.

In the recently published study, Cox notes that those findings on the protective effect of L-serine are promising and will be published separately.

Meanwhile a human experiment is underway. The US Food and Drug Administration has approved a trial of L-serine in ALS patients sponsored by Cox’s Institute of Ethnomedicine in Jackson Hole, and being conducted at Phoenix Neurological Associates, Phoenix, AZ.

More L-serine trials in humans are being developed with the Forbes Norris MDA/ALS Research and Treatment Center at California Pacific Medical Center and at the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center.

According to Clinical Trials.Gov, in the Phoenix trial, 20 patients with ALS are participating in the Phase I study, which will determine whether L-serine is safe. If it works, patients should have declining levels of BMAA in their blood, spinal fluid and urine. Ultimately, the studies will show if L-serine will slow or stop the progression of ALS.

In the first phase of the trials, subjects will get doses ranging from 0.5 grams twice daily up to 15 grams. Results are due in December, 2016.

A related trial, this time in patients with Alzheimer’s is being designed at Dartmouth Medical School, Cox said.

If successful, L-serine might be an effective treatment to slow or halt ALS, but Cox cautions that ALS is likely not a single disease.

“ALS is likely a syndrome rather than a single illness, with multiple pathways leading to the same set of symptoms,” he said recently.

About 8% to 10% of ALS cases are familial with half of those patients carrying an identified genetic mutation, Cox noted. The vast majority of the cases are sporadic, he said.

“These sporadic cases likely result from gene/environment interactions in which multiple genetic and environmental factors are at play,” Cox explained.

He is convinced however that one of those environmental factors appears to be exposure to blue-green algae.

Cyanobacteria are photosynthetic bacteria with an ancient history, one of the first know organisms on the planet. It is believed that cyanobacteria played a major role in generating the oxygen atmosphere of the earth.

Found in habitats ranging from the hot pools of Yellowstone National Park to the deserts of the middle east to the middle of the oceans, cyanobacteria are nearly ubiquitous on the earth’s surface, he explains. (Photo, blue-green algae mats at Yellowstone.)

That includes the sands of ancient seas and riverbeds in the near the Persian Gulf.

For that reason, breathing the dried up algae in desert sands could explain a significantly higher prevalence of ALS in Gulf War veterans.

Experts convened by the Institute of Medicine have agreed with the ALS Association that US military veterans appear to have an increased risk of developing ALS, and veterans deployed in the Gulf War of 1991 show a two-fold increased risk of developing ALS.

Among the possible factors raised by the experts were exposure to lead, pesticides, and extreme physical exertion. But other environmental exposures were also posited as a cause.

The IOM report “Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis in Veterans: Review of the Scientific Literature” is available from the National Academies Press.[link]

Cox believes blue-green algae exposure could also explain why there have been some ALS clusters in New Hampshire and in other regions where lakes are prone to blue-algae blooms. When waves break and people inhale the spray, they could be exposed, Cox has written.

As news of the apparent role of the neurotoxin continues to spread, researchers are taking a look of the possible health effects on people who consume blue-green algae in the form of Spirulina, a product touted as a health food. Spirulina might be just the opposite.

Cox said he has not data on that topic but he cites a recent paper by Susan Murch, a University of British Columbia researcher.

Murch and colleagues, writing in the Journal of AOAC International, Vol. 98, No. 6, 2015, looked at five commercial “natural health” products, protein power supplements containing Spirulina. The product labels put the Spirulina content at from 20% to 100%.

They found “several products were determined to contain BMAA” at varying levels.

Of course the food supplement market is notoriously unregulated, and the team expressed concerns.

“With research regarding the toxicity of BMAA ongoing, application of screening methods such as the one presented here, will help ensure the safety of these natural health product” they concluded.

Even when exposed to BMAA, not all people will develop symptoms.

But Miami FL researchers including Deborah Masher at the Miller School of Medicine, University of Miami and colleagues have found BMAA present in brain tissues of people who died with ALS.

Researchers in Sweden have found neonatal exposure in rodents can trigger neurological deficits later in life—raising the possibility that could be true for humans exposed in-utero as well.

“Much more research needs to be performed to determine the role that dose, duration and timing of BMAA exposure plays in the risk of the disease,” Cox said.

All photos courtesy of Paul Cox and the Institute for EthnoMedicine, Jackson Hole, WY