Article

Going South: The Toll of Smoking on Kentucky & West Virginia

Author(s):

Tobacco farm region physicians face the challenges of culture, law, and education in improving cessation.

A man walked into the practice of Mahmoud Moammar, MD, with his wife at his side and nothing more planned for his day beyond his follow-up with the local pulmonologist to see recent CT scan results.

He left that day with a death sentence—6 months to live, if he was lucky. The mass in his right lung was metastatic cancer and had already reached his liver and bones. It was too late to consider cold turkey, a nicotine patch, anything to yield his cigarette intake. His smoking habit was going to kill him.

These sudden tragedies are routine for Moammar at Catholic Health Initiatives (CHI) Saint Jospeh Health in Lexington. Medically trained in the New Jersey-New York area, the pulmonologist no longer flinches at the shocking rate of disease brought on by his patients’ smoking. It’s too frequently addressed, too frequently dismissed. In recalling this story to MD Magazine®, Moammar noted the man had started smoking as a teenager, and that not one person had made an effort to stop him before.

There’s plenty other stories. A female smoker came to him with obvious signs of undiagnosed chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). She was so burdened by the disease that she was unable to gather herself for a trip to the grocery store before seeking medical care.

Up in Smoke

Moammar called these diagnoses “terrifying,” in a vacuum. In Kentucky and West Virginia though, they are routine.There is no place with worse lung disease rates in the United States than the Kentucky-West Virginia region. Moving from east to west, the country’s tobacco farm belt stretches across Virginia and North Carolina to the ends of Indiana and Tennessee. At the epicenter are the 2 states known for their cigarette production and consumption—and the diseases they harbor.

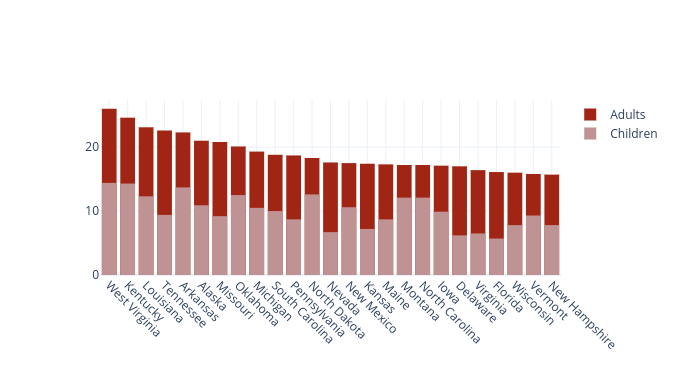

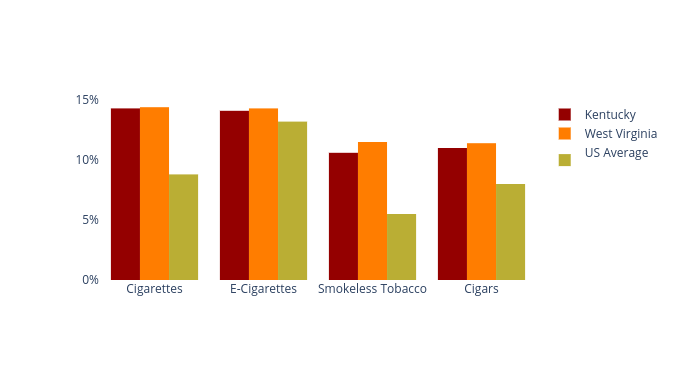

In 2017, about 15.5% of US adults smoked cigarettes, according to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). State-by-state rates peaked in West Virginia (26%) and Kentucky (24.6%). The 2 states also led in smoking rates among youths in 2017—14.4% and 14.3%, respectively, according to the CDC. A greater percentage of children were smoking cigarettes in West Virginia than adults in New York, Maryland, Massachusetts, and New Jersey.

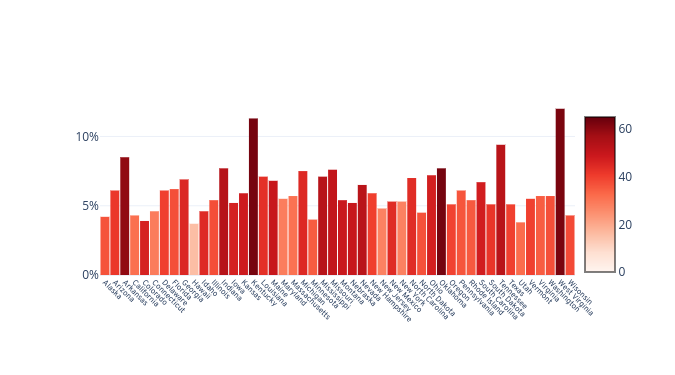

This all makes the geographic rates of COPD far easier to project. An article published in the Journal of the COPD Foundation last year reported that Kentucky (11.4%) and West Virginia (12%) were the only 2 states to report a COPD rate of more than 10% in its adult populations.

Though the CDC has projected age-standardized death rates due to COPD being on a steady fall since the 1990s, they remain high in the tobacco belt region. About 20 more people per 100,000 died from COPD in Kentucky (62.8) than the national average (44.3) in 2014.

Yet still, they smoke. Among the West Virginia population diagnosed with asthma, 28.3% reported using cigarettes in 2010. In Kentucky, the smoking rate among asthmatics was 32.3%.

Different Culture, Different Rules

These smoking and pulmonary disease associations, whether big or small, are consistent state by state in the US. What makes Moammar’s region of care so much more burdened by rates, he noted, are a layer of factors that each compound and perpetuate the issue. Simply put, smoking is a way of life and law in the South.Jennifer Folkenroth can see it on a bigger scale. The National Senior Director of Tobacco for the American Lung Association (ALA) and a former tobacco cessation counselor has seen the firsthand struggle of patients quitting their habits, just as she now sees the national rates continue to dominate in Kentucky and West Virginia. “We are seeing the same, consistent trending,” she told MD Mag®.

The ALA has chalked up these rates to a series of issues. A majority of states in these regions have set and maintained lower combustible cigarette tax rates—it’s “less expensive to feed the addiction,” she said.

Kentucky also has no law regarding smoke-free indoor air at designated places like private worksites, restaurants, and bars. It also provides no separate ventilation law—a practice followed by nearby states such as Virginia, West Virginia, Missouri, Texas, Oklahoma, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, and South Carolina.

These states, Albert Rizzo, MD, a pulmonologist and senior medical advisor at ALA, noted are unlikely to budge on their smoking policies and taxation. “Those states tend to have less aggressive laws for excised taxes on cigarettes—for ‘age 21’ type of laws,” he explained.

There’s also something to be said about patient access to care in this region. On average, rural state residents have greater distances to primary care providers, fewer options for specialists referral, and more risk for lost contact even after they seek out a healthcare provider. There’s no guarantee patients will follow up if the initial visit itself was too difficult.

What experts fear now is the issue turning inherent—the region’s youths are at an especially high risk of continuing the habit. Among high school students, Kentucky’s cigarette use rate is nearly twice that of the national average.

Beyond cigarettes, high school students in Kentucky are also using e-cigarettes (11.8% to 14.2%), smokeless tobacco (8.2% to 12.7%), and cigars (9.5% to 14.1%) at extreme rates. These rates are not unrelated, though. Folkenroth said the rates of dual tobacco product use in the West Virginia-Kentucky region are notably high.Regarding the e-cigarettes, Jackie Hayes, MD, pulmonary and critical care physician at Brooke Army Medical Center, explained that aside from a lack of data regarding long-term use and the products inside them, the devices pose real gateway dangers for youths not already smoking.

“One of the concerns is the safety and the potential harm to young people, but an even bigger concern is their potential as a gateway device to smoking traditional or tobacco cigarettes,” he explained.

In consideration to state youth smoking rates and their corresponding adult rates, Rizzo floated the belief the issue could also be a genetic one. While the influence of culture in this region may explain the ease by which adolescents can access and habitually use different tobacco products in this region, their desire to smoke in the first place may be as inherent as an addiction, such as alcoholism can be.

Changing the Norm

“The relationship is that tobacco leads to more lung disease—it’s usually not the other way around,” he said. “I don’t think there’s a real complete answer other than multiple factors, including culture and genetics.”Perhaps the most disheartening aspect of the entire issue, Rizzo noted, is the fact that smoking is the most preventable cause of death. These regions severely lack education on the benefits or methods of cessation. Even worse, a lack of use—not a lack of availability—of cessation interventions is impeding improvement, Moammar said. “Smoking cessation interventions are widely underutilized by both primary care and specialty providers,” he explained.

He suggested that all healthcare providers, particularly those in the South, begin recognizing a patient’s smoking status as a “vital sign,” and to include questions pertaining to it in any routine visit. Spending as little as 10 minutes with patients to discuss their smoking and ways to quit can make all the difference.

Rizzo added that lacking legislation is a key area of improvement, especially for youth smoking rates. Quoting the FDA’s own statement on the growing e-cigarette epidemic, he explained how e-cigarettes have placed tobacco products in children as young as middle school age. If the administration wants to fulfill its goal of limiting impressionable nicotine exposure in children, Rizzo suggested they will have to apply and enforce regulation against the marketing of e-cigarettes to children.

By preventing youth from even starting on tobacco products through education and legislation, cessation efforts should become even easier. Moammar noted a survey showing that about two-thirds of all smokers are willing to quit.

Reaching the End

“Patients have the desire to quit smoking, and they need education regarding the harms related to this problem and what to expect when they quit and during the process,” he emphasized. “They may stop smoking, and start again, because of withdrawal symptoms, stress, and weight gain.”It commonly takes the average smoker about a half-dozen attempts to fully, permanently quit. Moammar noted they aren’t just ending their smoking, though—they’re ending intricate habits woven into their daily lives. Therapies and interventions at care providers’ hands are intended to address that entire scope of cessation.

Among the 7 products approved by the FDA for aiding patients in quitting smoking, 5 are nicotine replacement therapies, and the other 2 are therapies indicated for the symptoms associated with withdrawal or addiction: bupropion (Wellbutrin) and varenicline (Chantix). Rizzo encouraged physicians to continue referring patients to such products—even if a patient had failed to reach cessation with it before.

He also stressed physicians should actively debunk and rebuke any false claims regarding the drugs’ effects which may potentially scare patients away from use. “That’s when the role of physicians can come into play,” he said. “They can ask, ‘Well, what were the things you heard, and what are some of the realistic benefits and side effects of the medication?”

Counseling and intervention to smoking can take many forms, in any medium—telephone discussions, internet-based cessation tools provided by the ALA and alike, face-to-face therapy, and so on. The distances rural patients feel between themselves and clinical care can be erased through telehealth measures.

As much as they need to learn about the means by which they can reach cessation, patients need to learn the greatest benefit of quitting: that their risk for disease and early death reduces the minute they stop smoking, Moammar said. More importantly, they need to know that fact is universal, not subject to change from any outside factor—their rate of smoking, their income, their residence, or even their age.

“Although the health benefits are greater for people who stop at earlier ages, there are benefits at any age, and you are never too old to quit,” he said.