Article

Harold Fernandez, MD: an Illegal Immigrant's Success Story

Author(s):

Smuggled here as a boy, Harold Fernandez, MD, overcame his illegal status and went on to become a prominent surgeon.

There are an estimated 11 million to 15 million immigrants living in the US without valid visas.

Call them illegal, undocumented, or unauthorized, the net is often the same.

They live in fear of being found out and deported.

Their status and future is a politically charged issue.

To some they are the nation’s best hope for the future.

For those at the other end of the political debate they are seen as a threat and a burden.

Harold Fernandez, MD, has heard it all. As a boy he entered the country illegally, used forged documents to stay here and enroll as a Princeton University undergraduate, living with guilt and anxiety for years before getting his green card.

But as near straight-A student at Princeton, a Harvard Medical School graduate, respected cardiac surgeon, and author, Fernandez feels his personal story is a testimony to the good that came of his deception.

“Those 15 million undocumented immigrants are here to be part of the American system, the American way of life, and they’re here to contribute—not to steal jobs or to break the law,” Fernandez said in a recent interview.

Fernandez is Chief of Cardiac Surgery at Southside Hospital in Bay Shore, NY.

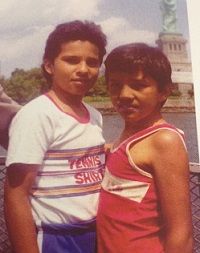

(Photo, right, Fernandez and brother Byron at Statue of Liberty)

He came here from Medellin, Colombia in 1978 when he was 13 years old.

His parents, who had emigrated earlier to find work and escape the drug-related violence of that city, paid to have him and his 11-year-old brother hidden in a small boat that one dark night crossed rough waters between Bimini in the Bahamas and Miami, FL.

“We landed at an abandoned port and we called a taxi cab and the taxi brought us to our friends,” he said.

From there, the friends arranged for the brothers to fly commercial to New York City where they were reunited with their parents.

His father worked in an embroidery factory, his mother in a clothing factory—with long hours and low pay-- and the family lived in a cramped apartment in West New York, NJ.

“We lived an underground existence with the ever-present fear of being uncovered,” he wrote in his book “Undocumented, My Journey to Princeton and Harvard and Life as a Heart Surgeon.”

In almost daily lectures, his father reminded them that they had “been given the chance of a lifetime by coming to the US and that if we squandered it, we would end up exactly where he was—working in a factor 12 hours a day for the minimum wage.” Education, he realized, was his only ticket out of his parents “vulnerable lives as undocumented immigrants.”

But by studying hard, doing well in athletics, becoming an Eagle Scout, and even getting an award for his standout performance as a newspaper delivery boy, Fernandez got the grades and reputation he needed to be admitted to Princeton University, where he pursed a degree in microbiology.

At a key juncture in his undergraduate career he admitted to advisors that he had forged documents, but his record at Princeton was so strong that he got the university’s support in pursuing legal residency.

“While I was at Princeton I wrote letters to everyone,” he said, “I wrote to President Reagan, to Bill Bradley, to the governor of New Jersey, Tom Kean.”

At a trial at which he presented his case, “The judge was very compassionate and he gave me and my family our residency cards,” Fernandez said. The legal argument, he said in his book, was that it would be a hardship on his youngest brother—an American citizen since he was born after the family arrived in the US—to have the family deported. But it was also likely, Fernandez feels, that the judge was convinced the family had a strong work ethic and potential to contribute to society.

Fernandez is not certain whether his letters the politicians had any impact.

After graduation and being accepted at medical school programs both at Johns Hopkins and a Harvard/Massachusetts Institute of Technology program, Fernandez attended Harvard/MIT and went on to specialize in cardiac surgery.

In his residency at New York University School of Medicine he became interested in blood vessels.

“My work really tailed trying to figure out how the endothelium reacts to injury,” he said, “also figuring out ways to manipulate that process and make it work better.”

He was part of a team that determined that a gene in the cell membrane that regulates the exchange of chloride and bicarbonate can have a defect that contributes to

high blood pressure, he said.

Though not all heart disease is genetic, the finding could explain some familial patterns, he said.

“Those patients have to be more vigilant about controlling all the other risk factors,” such as not smoking.

As part of an effort to spread the work, Fernandez has started a web-based program “El Show del Doctor Fernandez” that is “basically designed to inform patients in Spanish about some of the cardiovascular risk factors and about their own heart health.” There is a particular knowledge gap in the Latin community where there is “a lot of information about different products and different things that are not scientifically proven, not clinically accurate.”

Another problem for that community, he said, is that “a lot of times in the Hispanic and Latino community patients do not participate in their healthcare—they feel uncomfortable asking their physicians some of the questions that they should be asking.”

He feels much compassion towards these patients, he said, including those who may be here without authorization.

“These are people who love this country, you know, in a lot of ways, a lot of times even more than we do because they came here for education, for opportunity, and to be part of the American way of life.”