Article

Heartache Over New Cholesterol Treatment Guidelines

Author(s):

To produce the greatest impact from the implementation of the new American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association guidelines for the treatment of hypercholesterolemia in the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease (CVD), physicians should counsel patients on the benefits and risks of medication intervention to prevent CVD, but also explain the absolute necessity of regular exercise and abstention from tobacco use.

Wayne Altman, MD

and Frank J. Domino, MD

Review

Pencina MJ, Navar-Boggan AM, D’Agostino RB Sr, Williams K, Neely B, Sniderman AD, Peterson ED. Application of new cholesterol guidelines to a population-based sample. N Engl J Med. 2014 March 19. http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1315665.

Study Methods

Using the 2005 and 2010 National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) datasets, the study authors estimated the number and risk-factor profiles of patients who would be eligible for statin therapy under the new American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association (ACC-AHA) guidelines for the treatment of hypercholesterolemia in the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease (CVD),1 as compared with the Third Adult Treatment Panel (ATP III) of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP). The results were then extrapolated to a population of more than 115 million US adults aged between 40-75 years.

Results and Outcomes

Applying the new guidelines’ inclusion criteria to the US population would result in a statin eligibility increase of 43.2-56 million adult patients. Most of those newly recommended for statins would not have CVD, but rather a calculated CVD risk over the next 10 years of >7.5%.

Men aged 60-75 years would comprise the majority of the increase, resulting in 87% of men in this age group qualifying for statins according to the ACC-AHA guidelines, compared to the ATP III, under which approximately 30% of men qualified. Approximately 53% of women in this age group would meet the new guidelines’ inclusion criteria, up from about 21% currently — a surge based mostly upon the 10-year CVD risk calculation. Among those aged 40-60 years, statin eligibility would increase to roughly 30% from about 27%.

Conclusion

Clinically implementing the new ACC-AHA guidelines would result in an additional 12.8 million US adults becoming eligible for cholesterol-lowering treatment, the majority of whom would be older than age 60 and would not have CVD.

Commentary

New treatment guidelines often receive initial scrutiny, but later become the standard of care. The November 2013 release of the new ACC-AHA guidelines generated this initial discussion, and now the New England Journal of Medicine has offered a detailed review of its projected influence and addressed both medical quandaries, such as whether the evidence supports the balance of benefits of adoption of the guideline compared to the risks, and societal questions, such as whether the additional cost of implementation provides the best health outcomes in a country that already leads the world in healthcare money spent, but ranks around 50th in life expectancy.

Universal acceptance of the guidelines may potentially result in a relative risk reduction of about 25%, or nearly half a million fewer cardiovascular (CV) events over the next 10 years.2 Although many critics focus instead on muscle and liver damage from statin use, the risk of chemical hepatitis from statins or acute renal failure due to rhabdomyolysis are actually very small. Nevertheless, other risks are common.

The use of statins is predicted to prevent 1 CV event for every 150-200 adults treated, but it will also induce diabetes mellitus (DM) in 1 out of every 500 adults for low-dose statins, and 1 out of every 125 for high-dose statins.3 In addition, the use of statins on a large scale increases the risk of herpes zoster.4

Using a statin as a tool for the primary prevention of CVD may also make patients more complacent and undermine their lifestyle changes, which may have an even greater impact on the drug’s effect. In fact, previous data has demonstrated that cholesterol reduction through medication does little to obviate CVD risk when applied to sedentary individuals,5 and most of the trials incorporated in the guidelines’ development required diet and exercise training. As a result, no one can discern whether the broad use of statins without an emphasis on lifestyle will lower CVD risk.

By comparison, significant data supports the use of lifestyle changes — such as the Mediterranean diet for primary prevention of heart disease6 — and provide slightly better outcomes compared to the ACC-AHA guidelines. There is even data suggesting that eating an apple a day is just as effective as statins for the primary prevention of CVD.7

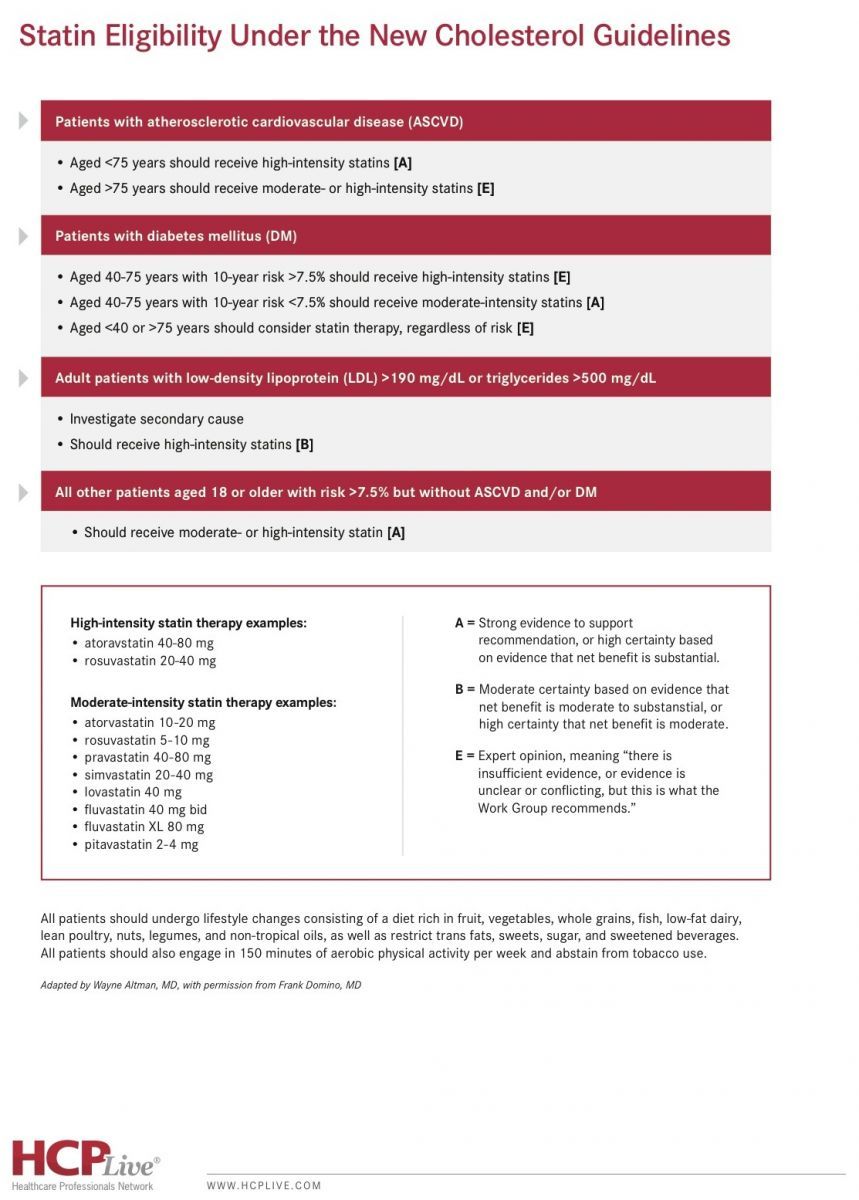

As summarized in the chart below, most of the new guidelines’ recommendations were not based on solid evidence, but rather on expert opinion. The implementation of the guidelines have “high sensitivity” in that they will add a medication to a small subset of patients who will have a CV event, but they have “low specificity” in that 90% of those taking a statin will derive no CV benefit and may even be harmed by statin-induced DM.

Click the image to download this chart on statin eligibility under the new cholesterol guidelines.

Until we know more, keep in mind:

- The new guidelines recognize that lifestyle modifications are still first-line for reducing CVD risk.

- There is strong evidence to support the use of high-intensity statin therapy for 3 patient populations: those with existing CVD, those with existing DM, and those with low-density lipoprotein (LDL) levels >190 mg/dL.

- In terms of the primary prevention of CVD, male patients aged 60-75 years will derive the highest benefit from statin use.

- Using the guidelines’ 10-year risk cutoff of 7.5%, statin therapy will prevent a CV outcome in 1 out of every 125-250 adult patients, but only among those who exercise. With the use of high-dose statins, the number of those who would be harmed by statin-induced DM is about the same.

To produce the greatest impact, physicians should counsel patients on the benefits and risks of medication intervention to prevent CVD, but also explain the absolute necessity of regular exercise and abstention from tobacco use. Debabrata Mukherjee, MD, MS, FACC, Editor-in-Chief of Cardiology Review and Chief of Cardiovascular Medicine and Chairman of the Department of Internal Medicine at the Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center at El Paso, supports such patient-centered discussion, as he noted “the guidelines have laid out important principles, but physicians need to engage patients in the decision-making and individualize therapy based on risks and benefits for the individual patient.”

“Clinicians should focus on appropriate lifestyle interventions, including diet and exercise, and address other modifiable risk factors in addition to lipid levels,” Mukherjee advised.

References

1. Stone NJ, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. Circulation. 2013 Nov 12. http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/early/2013/11/11/01.cir.0000437738.63853.7a.full.pdf

2. Taylor F, et al. Statins for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 Jan 31;1:CD004816. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23440795.

3. Solis AB, Pilemann-Lyberg S, Gæde P. Ugeskr Laeger. 2014 Feb 3;176(3):227-31. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24629749.

4. Antoniou T, Zheng H, Singh S, Juurlink DN, Mamdani MM, Gomes T. Statins and the risk of herpes zoster: a population-based cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. 2014 Feb;58(3):350-6. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24235264

5. Kones R. Primary prevention of coronary heart disease: integration of new data, evolving views, revised goals, and role of rosuvastatin in management. A comprehensive survey. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2011;5:325-80. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21792295.

6. Estruch R, et al. Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with a Mediterranean diet. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1279-90. http://www.nejm.org/doi/pdf/10.1056/NEJMoa1200303.

7. Briggs ADM, Mizdrak A, Scarborough P. A statin a day keeps the doctor away: comparative proverb assessment modeling study. BMJ. 2013;347:f7267. http://www.bmj.com/content/347/bmj.f7267.

About the Authors

Wayne J. Altman, MD, is Family Medicine Director of Medical Student Education and Associate Professor of Family Medicine at Tufts University School of Medicine.

He was assisted in writing this article by Frank J. Domino, MD, Professor and Pre-Doctoral Education Director for the Department of Family Medicine and Community Health at the University of Massachusetts Medical School and Editor-in-Chief of the 5-Minute Clinical Consult series (Lippincott Williams & Wilkins).