Article

Injectable corticosteroids for the painful shoulder: Patient evaluation

ABSTRACT: Management with corticosteroid injections should beconsidered for a variety of painful shoulder conditions, such ascervical, acromioclavicular, subacromial, glenohumeral, and bicepstendon pathology. Several aspects of the physical examination areused to isolate the anatomical source of a patient's shoulder pain.Knowing how to perform provocative maneuvers and evaluate theresults is critical for making the diagnosis and identifying potentialcorticosteroid/anesthetic injection sites. In our comprehensive16-step shoulder examination, radiographs are not viewed initiallyto avoid bias that can lead to inaccurate diagnosis. When commonprovocative maneuvers for shoulder conditions are used in isolation,their sensitivity and specificity typically are lower than whenthey are used in combination. Obtaining high-quality radiographs isessential. (J Musculoskel Med. 2008;25:236-245)

A variety of painful shoulder conditions might warrant consideration for management with corticosteroid injections. Most physicians have a general knowledge of how to obtain a pertinent history for shoulder problems, but some may have minimal training for making a diagnosis of some specific shoulder conditions. For example, differentiating cervical, acromioclavicular (AC), subacromial (SA), glenohumeral (GH), and biceps tendon pathology may be particularly challenging.

Various aspects of the physical examination are used frequently to isolate the anatomical source of a patient's shoulder pain, especially provocative maneuvers, signs, and tests; radiography also is useful. Knowing how to perform provocative maneuvers and evaluate the results is critical for making the diagnosis and identifying potential corticosteroid/anesthetic injection sites.

This 3-part article describes the diagnostic and therapeutic uses of corticosteroid/anesthetic injections for painful shoulder conditions. In the first part ("The use and misuse of injectable corticosteroids for the painful shoulder," The Journal of Musculoskeletal Medicine, February 2008, page 78), we reviewed the mechanism of action of corticosteroids, current preparations, indications and contraindications, adverse effects, misuses, and lack of uniform standards of care. This second part discusses physical examination and radiographic evaluation procedures for determining when to inject corticosteroids. In the third part, to appear in a later issue of this journal, we will illustrate techniques for administering injections for specific shoulder complaints. We hope that this discussion will encourage the development of more uniform guidelines and help improve injection accuracy.

GENERAL GUIDELINES

A 16-step physical examination

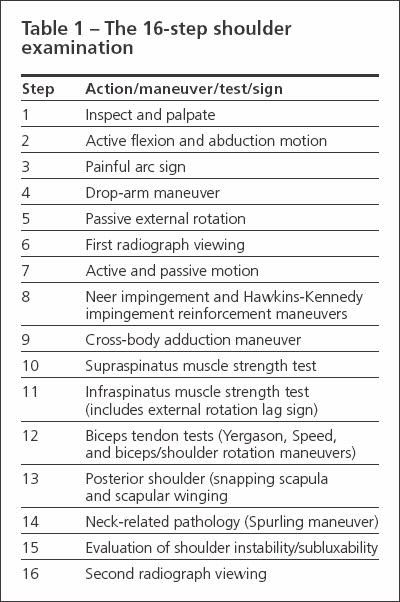

There are various descriptions of how to perform a comprehensive shoulder examination.1,2 The examination performed for a typical patient seen in our orthopedic shoulder specialty clinic includes 16 basic steps (Table 1). In this examination, radiographs are not viewed initially to avoid bias that can lead to a premature/inaccurate diagnosis (eg, when AC arthritis is seen on radiographs but the AC joint is not a significant source of pain).The steps are as follows:

Table 1

- Step 1. Inspect and palpate the shoulder. This is facilitated by asking women to wear a shoulder examination gown or having men remove their shirt.

- Step 2. The patient is asked to demonstrate active flexion and abduction motion until he or she feels significant pain in each direction. This provides the examiner with a general "feel"-at the beginning of the examination-for the magnitude of the patient's shoulder pain and functional limitations. If the patient cannot raise his arm more than about 70° to 80° in either flexion or abduction, he probably has a full-thickness supraspinatus tear, significant arthritis, adhesive capsulitis (frozen shoulder), or all of these conditions.

- Step 3. The painful arc sign is elicited by asking the patient to actively elevate his arm in the scapular plane until full elevation is reached and then having him lower the arm in the same arc. The test result is positive when the patient has pain or painful catching between 60° and 120° of elevation.

- Step 4. The drop-arm maneuver result is considered positive if the patient's arm drops suddenly or he experiences severe pain (generally seen around 90° of elevation) and probably represents rotator cuff pathology. In some cases of significant rotator cuff pathology, the patient can hold his arm in abduction, but applying a small amount of downward force causes the arm to drop.

- Step 5. The examiner performs the passive external rotation maneuver by externally rotating the patient's arm with his elbow at his side.This maneuver helps detect pain and crepitation that might be attributable to GH arthritis.

- Step 6. If pain is elicited, radiographs are viewed (the first radiograph viewing) to determine the severity of GH arthritis and humeral head elevation (both are present in rotator cuff tear arthropathy, which is a chronic rotator cuff tear with GH arthritis). For patients who do not have GH arthritis, the passive external rotation maneuver usually is pain-free. If radiographs reveal significant GH arthritis, the examiner should anticipate that the patient probably also will have difficulty in the portion of the examination involving possible SA impingement syndromes. During all examination maneuvers, observe for painful facial expressions and frequently ask the patient whether he is experiencing pain. Doing so is especially important with additional provocative maneuvers, which can be quite painful.

- Step 7. Determining the difference between active and passive motion in all planes also is important. If motion is generally restricted, and active and passive ranges are similar, the patient might have adhesive capsulitis or moderate to severe GH arthritis. If crepitation is felt and pain is evoked during external rotation (with the patient's elbow at his side), there may be significant GH arthritis; this scenario is more common than adhesive capsulitis.

- Step 8. Next, perform the Neer impingement and Hawkins-Kennedy impingement reinforcement maneuvers to evaluate SA impingement syndromes. The Neer impingement maneuver is performed with the examiner causing forced forward flexion of the patient's upper extremity (with elbow extended and forearm pronated) while the examiner's other hand prevents compensatory upward scapular rotation.This maneuver causes the greater tuberosity of the humerus to encroach on or impinge against the anterior acromion.3-5

The Hawkins-Kennedy maneuver is performed by forward flexion of the humerus to 90° combined with maximal internal rotation of the shoulder.6 Most patients seen in our shoulder specialty clinic have pain with 1 or both of these maneuvers, reflecting the somewhat high prevalence of SA impingement syndromes.

- Step 9. The examiner performs the cross-body adduction maneuver by having the patient forward flex his shoulder to 90° and by adducting the arm across the body. The result is positive if the test causes pain in the shoulder region. This maneuver helps determine the presence of significant AC pathology and may elicit pain from the SA space or nearby regions. The pain elicited with this maneuver is compared with that of the previous maneuvers to further determine the source of pain.

- Step 10. The supraspinatus muscle strength test is performed by resisting abduction of the patient's arm elevated to 90° in the plane of the scapula.The forearm is in internal rotation.

- Step 11. In the infraspinatus muscle strength test, the patient's elbow is flexed to 90° and the arm is adducted to the trunk (at the side) in neutral rotation. The examiner then applies an internal rotation force to the arm while the patient resists.The result is positive if the patient "gives way" because of weakness or pain or if there is a positive external rotation lag sign.

For that sign, the patient's arm is positioned with the elbow at the side and flexed to 90°. Then the arm is maximally externally rotated by the examiner and the patient is asked to hold this position. If the patient cannot and the arm falls into internal rotation, it is considered a positive test result. GH instability also should be assessed, especially in patients who are younger than 45 years, because it can cause secondary SA impingement.

- Step 12. Next, perform provocative tests for biceps pathology, including the Yergason, Speed, and biceps/shoulder rotation maneuvers. These tests help determine whether pathology attributable to the biceps tendon warrants injecting the biceps sheath.

The Yergason maneuver is performed by having the patient flex his elbow to 90° and actively supinate his forearm against resistance applied by the examiner to elicit pain at the bicipital groove. In the Speed maneuver, have the patient forward flex his humerus with his forearm supinated and elbow extended; the examiner applies resistance.

In the biceps/shoulder rotation maneuver, the examiner's finger applies pressure on the patient's anterior shoulder (over the biceps tendon sheath) while the examiner passively moves the patient's arm slowly in internal and external rotation. The result is positive if pain occurs when the biceps sheath is anterior (when the arm is in about 10° of internal rotation).

- Step 13. The patient also may have pain in the posterior aspect of the shoulder caused by scapulothoracic bursitis; if it is present, an injection may be given. This pathology usually is seen as subscapular pain and crepitation or a "popping/catching" sensation with arm elevation.

To detect these signs, the examiner performs the subscapular crepitation maneuver by placing his hand on the posterior aspect of the scapula while the patient tries to reproduce the symptoms. We also examine for scapular winging (the medial border of the scapula moves away from the posterior chest wall); if it is seen, electrodiagnostic studies (eg, nerve conduction studies/electromyography) might be warranted.

- Step 14. The Spurling maneuver is performed to determine whether some percentage of the patient's pain is the result of cervical pathology.7 The examiner rotates and bends the patient's neck toward the affected shoulder with downward compression applied on the patient's head. The neck should be flexed and extended. When the Spurling maneuver elicits significant pain (estimated at more than 70% of the "shoulder" pain) but provocative maneuvers for the SA space and AC and GH joints do not, shoulder injections usually are not indicated and diagnostic workup for neck pathology may be commenced (eg, neurological testing, cervical spine radiography, and MRI).

- Step 15. In this step, the patient usually is asked to lie on his back for the "crank" maneuver, which helps detect GH instability (pain or discomfort with excessive translation of the humeral head on the glenoid fossa during active shoulder motion) or subluxability (symptomatic instability without complete separation or dislocation of the articular surfaces).The crank maneuver is performed by having the involved shoulder positioned so that the scapula is supported by the edge of the examining table and the proximal humerus is placed in various degrees of external rotation and abduction. Patients with significant instability usually worry that there will be pain or the shoulder will feel like it is "slipping" out of the joint.

The Jobe relocation maneuver (relocation test) provides confirmation that these symptoms result from instability. Confirmation is obtained when the pain/apprehension from the crank maneuver subsides with the application of a posterior-directed force to the upper arm.

Presence of the "sulcus" sign also helps determine the presence of instability. This sign is elicited by pulling firmly downward on the patient's arm while he is sitting with the arm at his side; observation of a depression, or sulcus, forming just lateral to the acromion is a positive finding.

The patient also usually sits upright for the "jerk" maneuver, which tests for posterior instability. The patient internally rotates and forward flexes his humerus to 90°.The examiner then stabilizes the scapula with 1 hand; the other causes a posterior force by pressing in a posterior direction on the elbow. A positive result is felt with the humeral head sliding excessively backward. As in all instability testing, evaluation of the contralateral side is essential for detecting significant asymmetrical findings.

If there is evidence of GH instability without significant GH arthritis, no injection should be given at the GH joint, because doing so could mask the protective effect of pain. However, there may be SA symptoms that are secondary to GH instability ("secondary SA impingement"). In these cases, SA injections might be warranted. At this time, the examiner should have sufficient information to determine whether a corticosteroid injection is warranted.

- Step 16. After the first 15 steps of the shoulder examination are completed, the radiographs are reexamined (the second radiograph viewing), even though the physical examination is not yet complete. Additional physical examination steps could include deep tendon reflex testing, neurosensory evaluation, and other special tests.

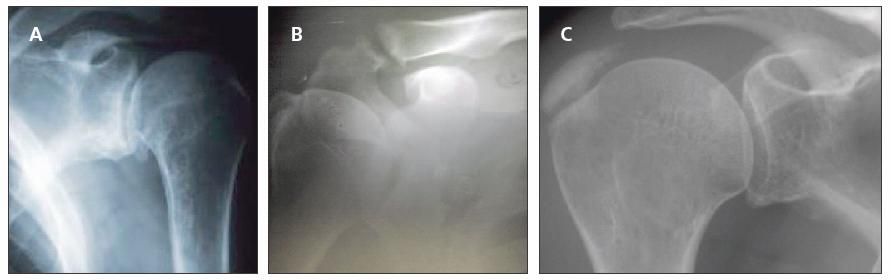

An assessment of acromial morphology is made.There are 3 types of acromion that may be associated with rotator cuff pathology. Type 1 acromion has a flat undersurface and is associated with the lowest prevalence of rotator cuff pathology, type 2 has a curved undersurface, and type 3 has a hooked undersurface.

We also determine the degree of arthritis at the GH joint, which may be quantified as 0, normal; 1, mild (osteophytes smaller than 3 mm on the humerus); 2, moderate (osteophytes 3 to 7 mm on the humerus); or 3, severe (osteophytes larger than 7 mm on the humerus) (Figure).8 Arthritis of the AC joint also may be categorized (none, mild, moderate, or severe).8 Calcific tendinitis, which typically occurs near the insertion of the supraspinatus, may be quantified as 1, small (less than 0.5 mm); 2, medium (0.5 to 1.5 mm); or 3, large (greater than 1.5 mm).9

Figure – In the final step in a comprehensive shoulder examination, radiographs are re-examined even though the physical examination is not yet completed. These radiographs show moderate glenohumeral arthritis (A), moderate acromioclavicular arthritis (B), and large calcific tendinitis (C).

Sensitivities and specificities

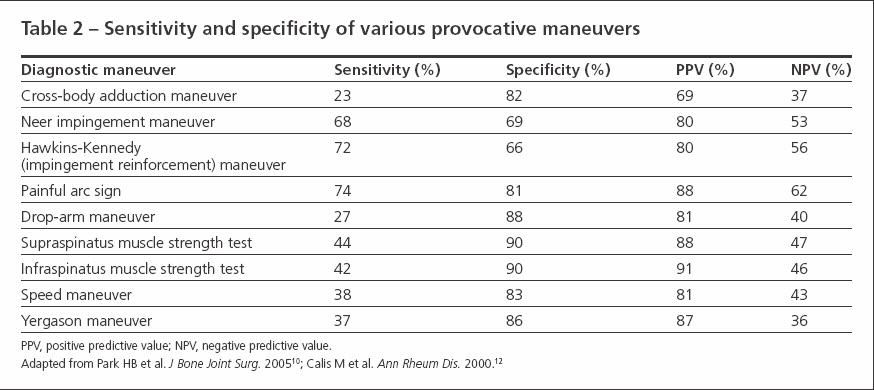

Studies have shown that when common provocative maneuvers for shoulder conditions are used in isolation, their sensitivity and specificity typically do not exceed 60% and 85%, respectively (Table 2).

Table 2

However, a more recent study rigorously evaluated 8 physical examination tests/maneuvers in 1127 patients who had shoulder surgery.10

The authors determined the diagnostic values of the tests/ maneuvers/signs, including their probabilities in predicting bursitis and partial-thickness and full thickness rotator cuff tears. When each test was evaluated independently, the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, and overall accuracy varied considerably.

However, when 3 tests were used in combination, the predictive strengths improved substantially. For example, the painful arc sign, Hawkins-Kennedy impingement sign, and infraspinatus muscle test used in combination yielded the best posttest probability (95%) for any degree of impingement syndrome.The combination of the painful arc sign, drop-arm sign, and infraspinatus muscle test produced the best posttest probability (91%) for full-thickness rotator cuff tears.

Acquiring radiographs

Obtaining high-quality radiographs, including views that show the SA arch, is essential. Views that are especially helpful include the supraspinatus outlet view for the SA space, the Zanca view for the AC joint, the true anteroposterior view, the scapular Y view, and the axillary-lateral view. The Zanca, anteroposterior, scapular Y, and axillary-lateral views are sufficient for most patients.

CLINICAL CONDITIONS

SA bursitis/impingement syndrome

The SA bursa is one of the most frequently injected areas of the shoulder. The Neer impingement and Hawkins-Kennedy impingement reinforcement maneuvers are important for demonstrating the painful arc of motion that occurs with SA impingement syndromes. The supraspinatus and infraspinatus strength tests and drop-arm and painful arc maneuvers also help.

Strength testing should be performed after the local anesthetic has taken effect because in some cases, there may be notable improvements in supraspinatus strength testing results.The drop-arm maneuver may improve notably or become absent; when there is improvement, we often steer away from ordering an MRI scan toward physical therapy while adopting a "wait and see" approach to see if improvement is sustained. In these cases,what initially appeared to be stage 3 SA impingement (with a full-thickness rotator cuff tear) might be stage 2 (no rotator cuff tear) or stage 3 with a partial but nonoperative rotator cuff tear.

Inflammation (tendinitis/ tenosynovitis) and tendinosis

The Yergason and Speed maneuvers are helpful in examining the biceps tendons. Directly palpating biceps tendons (biceps/shoulder rotation maneuver) also is important. The maneuvers described for SA impingement syndromes should be used for evaluating the rotator cuff.

Osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis

The cross-body adduction maneuver usually elicits pain when there is significant AC arthritis. However, the Hawkins-Kennedy impingement reinforcement maneuver also may elicit pain from the AC joint. Analyzing radiographs for this disorder is important; the Zanca radiographic view is most helpful. Selective diagnostic injections are quite useful in identifying AC joint pathology as a significant source of pain because the cross-body adduction maneuver has low sensitivity (about 23 %) (see Table 2).

For GH arthritis, internally and externally rotate the arm with the elbow at the patient's side; feel for crepitus and pain localized to the shoulder. In addition, look for decreased range of motion (with similar active and passive motion) and analyze radiographs.

Other less-common arthritides may occur (eg, calcium pyrophosphate deposition disease, chondrocalcinosis, and gout). In these cases, making the diagnosis often requires crystallographic analysis of joint fluid and additional metabolic workup.

Rotator cuff tear arthropathy

This condition is characterized by the presence of a chronic full-thickness supraspinatus tear and GH arthritis. Additional characteristics include advanced GH changes, often with mild evidence of humeral head collapse, and erosion of the acromion and associated structures leading to GH incongruity.

Patients typically present with complaints of restricted motion and moderate to severe pain that does not subside adequately with oral anti-inflammatory medications. Simple arm movements may be limited because of weakness, crepitation, and sharp pain, and overhead reaching usually is not possible. Corticosteroid injection at 4- to 6-month intervals helps alleviate pain in cases in which surgery is not a viable option.

Subacute strains and sprains

Treatment with injections is considered for significant residual pain resulting from a sprain or strain (eg, post-traumatic bursitis or tendinitis). However, injections typically are not given within 3 weeks of the injury to allow for initial healing. For maneuvers that test for the specific strain or sprain of SA structures, see the SA impingement section above. If significant pain persists at 1 to 2 weeks postinjection, consider using MRI to determine whether there has been a tear of a tendon, the capsular ligaments, or the glenoid labrum.

GH instability and secondary SA impingement

In this case, the unstable GH joint moves excessively upward toward the acromion during overhead elevation of the arm. A rule of thumb is to inject the SA space but usually not the GH joint, because injection of an unstable joint that can be subluxated reduces the protective benefit of pain, potentially leading to use-related increased inflammation that could result in increased pain after the analgesic effect of the corticosteroid has dissipated.

Determining whether the patient can voluntarily dislocate or nearly dislocate (subluxate) his shoulder also is important. Voluntary dislocators/subluxators with secondary SA impingement typically do not benefit from corticosteroid injections; they often require physical therapy or behavioral counseling or both because of the important psychological dimensions of this condition. The crank, relocation, and jerk maneuvers help elicit instability. The Neer and Hawkins-Kennedy maneuvers also help establish SA impingement that might result from GH instability.

Calcific tendinitis

Use the diagnostic maneuvers described for SA impingement syndromes. The presence of calcific tendinitis is confirmed by the presence of 1 or more radiopacities in the vicinity of the supraspinatus or other rotator cuff tendons (see Figure).This lesion is not injected directly with corticosteroids, but injections into the SA bursa may be done in conjunction with "needling" of the calcific deposit.11

Adhesive capsulitis

There is severely decreased range of motion on physical examination with adhesive capsulitis; active and passive motion are similar. Also, external rotation often is severely decreased. Coupled with these findings, radiographs are essential for distinguishing this condition from GH arthritis.

Trigger points (localized myofascial pain)

These points are characterized by local tender, self-sustaining hyperirritable foci located in skeletal muscle or surrounding fascia or in a zone of referred pain. A common shoulder trigger point occurs over the insertion of the levator scapula muscle into the superior angle of the scapula. When this trigger point is present with types 2 and 3 of SA impingement syndrome, we hypothesize that it results from excessive/repetitive traction by this muscle because it causes compensatory scapular elevation as a means for relieving SA pain by increasing the superoinferior dimensions of the SA space.

Scapulothoracic bursitis and snapping scapula syndrome

Palpation over the posterior scapula during range of motion (eg, abduction) reveals crepitation, pain, or popping (often called "snapping scapula syndrome") generally beneath the medial or superomedial aspects of the scapula. Surgery is more common in younger patients (younger than 20 years) than in older ones because symptoms are more likely caused by an excessively curved superior scapular angle. Older patients and those who had antecedent trauma to the scapular region are more likely to benefit from corticosteroid injections. Nonoperative resolution of symptoms might require activity modification coupled with 3 to 5 corticosteroid injections administered over 1 to 2 years.

Subcoracoid impingement

This condition, which typically occurs in adolescent and teenage populations, is rare even in a shoulder specialty practice. CT scans and selective local anesthetic injections often are needed to make the diagnosis; corticosteroid injections are not useful for this condition. If subcoracoid impingement is suspected, referring the patient to an orthopedic specialist might be prudent.

CONCLUSION

Understanding and following a standard "checklist" during the physical examination, coupled with an adequate radiographic evaluation, may help examiners target shoulder areas that could benefit from corticosteroid injections. By using the immediate effect of the local anesthetic to distinguish nonaffected from affected areas of the shoulder, clinicians can minimize misuse or overuse of these injections and enhance their therapeutic effects. In part 3, we will describe techniques for administering injections for specific shoulder conditions and advanced/detailed and basic/quick algorithms for evaluating and injecting painful shoulder conditions.

References:

- Hawkins R, Bokor D. Clinical evaluation of shoulder problems. In: Rockwood C, Matsen F, eds. The Shoulder. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1998:165-197.

- Shankwiler JA, Burkhead WZ. Evaluation of painful shoulders: entities that may be confused with rotator cuff disease. In: Burkhead WZ, ed. Rotator Cuff Disorders. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1996:59-72.

- Neer CS 2nd. Impingement lesions. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1983;173:70-77.

- Pappas GP, Blemker SS, Beaulieu CF, et al. In vivo anatomy of the Neer and Hawkins sign positions for shoulder impingement. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2006;15:40-49.

- Valadie AL 3rd, Jobe CM, Pink MM, et al. Anatomy of provocative tests for impingement syndrome of the shoulder. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2000;9:36-46.

- Hawkins RJ, Kennedy JC. Impingement syndrome in athletes. Am J Sports Med. 1980;8:151-158.

- Cipriano JJ. Cervical orthopaedic tests. In: Cipriano JJ, ed. Photographic Manual of Regional Orthopaedic and Neurological Tests. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003:39-91.

- Brox JI, Lereim P, Merckoll E, Finnanger AM. Radiographic classification of glenohumeral arthrosis. Acta Orthop Scand. 2003;74:186-189.

- Uhthoff HK, Loehr JF. Calcifying tendinitis. In: Rockwood CA, Matsen FA, eds. The Shoulder. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1998:989-1008.

- Park HB, Yokota A, Gill HS, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of clinical tests for the different degrees of subacromial impingement syndrome. J Bone Joint Surg. 2005;87A:1446-1455.

- Hennigan SP, Romeo AA. Calcifying tendinitis. In: Iannotti JP, Williams GR, eds. Disorders of the Shoulder: Diagnosis and Management. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1999:129-157.

- Calis M, Akgün K, Birtane M, et al. Diagnostic values of clinical diagnostic tests in subacromial impingement syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis. 2000;59:44-47.