Publication

Article

Cardiology Review® Online

Is CKD a Coronary Heart Disease Risk Equivalent?

German T. Hernandez, MD , FASN, FACP

Review

Tonelli M, Muntner P, Lloyd A, et al. Risk of coronary events in people with chronic kidney disease compared with those with diabetes: a population-level cohort. Lancet.

2012;380:807-814.

The US National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III recommends reduction of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL) levels to <100 mg/dL in people with known coronary heart disease (CHD) or those with a disorder designated as a CHD equivalent. 1 Diabetes is considered a CHD equivalent as it carries a risk of a major coronary event equal to that for people with a prior myocardial infarction (MI) or a 10-year risk of MI or coronary death >20%.2 While chronic kidney disease (CKD) has been strongly associated with the development of cardiovascular events and mortality, it has not yet been established as a CHD equivalent.3-5 Recently Marcello Tonelli, MD, and colleagues assessed whether CKD is a CHD equivalent using a populationbased cohort in Alberta, Canada.6

Study Details

The authors evaluated the risk of first hospitalization for MI and all-cause mortality in people with a prior MI, diabetes, or non—dialysis-dependent CKD (estimated glomerular filtration rate [eGFR] between 15 mL/min/1.73 m2 and 60 mL/min/1.73 m2—stage 3 or 4 kidney disease). Using the Alberta Kidney Disease Network database, adult outpatients without end-stage kidney disease and whose serum creatinine had been measured between 2002 and 2009 were identified for inclusion in the population-based cohort study. Subjects were classified as having CKD if the eGFR by the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiological Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation was between 15 mL/min/1.73 m2 and 59 mL/min/1.73 m2. Five risk groups were used for the analysis:

• all subjects with a prior MI (regardless of presence or absence of CKD or diabetes)

• 4 groups of subjects without a prior MI, which included:

• patients with CKD but without diabetes,

• patients with diabetes but without CKD,

• patients with both diabetes and CKD,

• patients with no CKD and no diabetes.

The primary study outcome was first hospitalization for MI; the secondary outcomes were all-cause mortality for all subjects and all-cause mortality following a new MI. Outcomes were determined until the study’s end date of March 31, 2009.

A total of 1,268,029 participants met the inclusion criteria. At study entry, only 12,960 participants had a prior MI, 15,368 had diabetes and CKD, 59,117 had CKD without diabetes, and 1,104,713 had no diabetes or CKD. After a median follow-up period of 48 months, the unadjusted rate of MI was highest among people with a prior MI (18.5 per 1000 person- years; 95% confidence interval [CI], 17.4-19.8). The rates for MI in both groups with no prior MI (one of which had CKD and no diabetes, and the other with diabetes but no CKD) were lower compared with the group with a prior MI.

When comparing the rate of MI between groups without a previous MI, the unadjusted rate of incident MI was higher for the group with CKD but no diabetes compared with the group with diabetes but no CKD (6.9 vs 5.4 per 1000 person-years; P <.0001). However, after multivariable adjustment (for age, sex, socioeconomic status, and comorbid conditions), the relative rate of MI was lower for people with CKD but no diabetes than for people with diabetes but no CKD: 1.4 (95% CI, 1.3-1.5) versus 2.0 (95% CI, 1.9-2.1), using as the reference group the patients with no prior MI, no diabetes, and no CKD.

When restricting the analyses of the CKD group to include an eGFR between 15 mL/min/1.73 m2 and 59 mL/ min/1.73 m2 and severe proteinuria, the adjusted rate of MI was similar to the diabetes group. Furthermore, when a more severe CKD definition was used (an eGFR between 15 mL/ min/1.73 m2 and 44 mL/min/1.73 m2 and severe proteinuria), the rate of MI was higher for the CKD group (12.4 per 1000 person-years; 95% CI, 9.7-15.9) compared with the diabetes group (6.6 per 1000 person-years; 95% CI, 6.4-6.9).

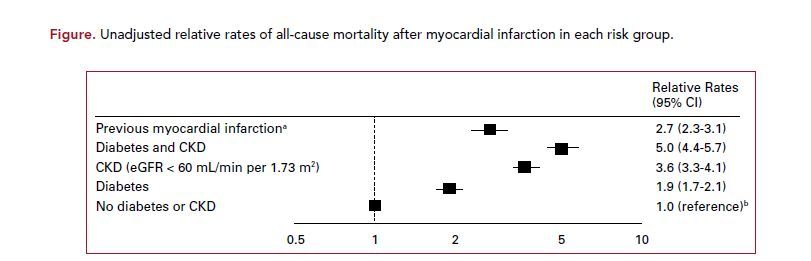

The adjusted all-cause mortality relative rate was fairly similar among people with a prior MI (1.4, 95% CI 1.4-1.5), CKD (1.3, 95% CI 1.3- 1.3), and diabetes (1.4, 95% CI 1.3- 1.4). However, the unadjusted 30-day mortality following an MI was higher for the CKD group (14%) compared with the diabetes with no CKD group (8%; P <.0001) and when compared with the previous MI group (10%; P = .0053). Furthermore, the unadjusted long-term, all-cause mortality relative rate was higher for the CKD group (3.6; 95% CI, 3.3-4.1) compared with the diabetes group (1.9; 95% CI, 1.7- 2.1) and compared with the prior MI group (2.7; 95% CI, 2.3-3.1) (Figure).

When considering the group without previous MI but with diabetes and CKD, both the rates of MI and all-cause mortality were similar to or exceeded the rates in the prior MI group. Additionally, following an admission for an MI, the all-cause longterm relative rate of mortality was highest for the diabetes with CKD group (5.0; 95% CI, 4.4-5.7).

References

1. Executive Summary of The Third Report of The National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High

Blood Cholesterol In Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). JAMA. 2001;285:2486- 2497.

2. Grundy SM. Diabetes and coronary risk equivalency: what does it mean? Diabetes Care. 2006;29:457-460.

3. Go AS, Chertow GM, Fan D, McCulloch CE, Hsu CY. Chronic kidney disease and the risks of death, cardiovascular events, and hospitalization. N Engl J Med.

2004;351:1296-1305.

4. Hernandez G, Sippel M, Mukherjee D. Interrelationship between chronic kidney disease and risk of cardiovascular diseases. Cardiovasc Hematol Agents Med Chem.

[published online ahead of print June 20, 2012] http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22721441. Accessed September 30, 2012.

5. Sarnak MJ, Levey AS, Schoolwerth AC, et al. Kidney disease as a risk factor for development of cardiovascular disease: a statement from the American Heart Association Councils on Kidney in Cardiovascular Disease, High Blood Pressure Research, Clinical Cardiology, and Epidemiology and Prevention. Hypertension.

2003;42:1050-1065.

6. Tonelli M, Muntner P, Lloyd A, et al. Risk of coronary events in people with chronic kidney disease compared with those with diabetes: a population-level cohort

study. Lancet. 2012;380:807-814.

7. Baigent C, Landray MJ, Reith C, et al. The effects of lowering LDL cholesterol with simvastatin plus ezetimibe in patients with chronic kidney disease (Study

of Heart and Renal Protection): a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2011;377:2181-2192.

Commentary

Consider Lipid-Lowering Therapy

This study by Tonelli et al aimed to assess whether CKD constitutes a CHD risk equivalent. The study has many strengths, including a large sample size, the use of a

methodologically rigorous population-based registry, and the inclusion of a significant proportion of participants with more severe CKD (eGFR between 15 mL/min/1.73 m2 and 44 mL/min/1.73 m2). The study has few limitations, the most notable of which is the reliance on a relatively short-term follow-up period of 4 years to establish a 10-year risk of MI.

In terms of the primary analyses, the study results do not strictly support the designation of CKD (defined as an eGFR between 15 mL/min/1.73 m2 and 59 mL/min/1.73 m2) as a CHD risk equivalent. The rate of first MI in the CKD-only group was lower than 20 per 1000 person-years and was significantly lower than the rate for the group with a previous MI. However, the study results do show that when a more severe definition of CKD is used (eGFR, 15 mL/ min/1.73 m2 to 44 mL/min/1.73 m2 with concomitant severe proteinuria), the rate of first MI in people with CKD exceeds that in people with diabetes, a condition already established as a CHD equivalent.

Furthermore, the study also shows that following hospitalization for an MI, the highest relative rate of all-cause unadjusted mortality is among the diabetes and CKD group, followed by the CKD-only group, and both rates exceed the rate for the previous MI group.

The Study of Heart and Renal Protection (SHARP) trial used low-dose lipid-lowering therapy versus placebo in 9270 patients with moderate to severe CKD (25% had severe proteinuria and 28% had an eGFR of 15 mL/min/1.73 m2 to 29 mL/min/1.73 m2) and without a prior MI. The use of lipid-lowering therapy did not significantly reduce the incidence of MI or CHD death, but it did decrease the incidence of major atherosclerotic events, non-hemorrhagic strokes, and arterial revascularization

procedures.7

While Tonelli’s study does not support the use of CKD as a CHD risk equivalent based solely on defining CKD as an eGFR between 15 mL/min/1.73 m2 and 59 mL/min/1.73 m2, it seems a reasonable approach to consider lipid-lowering therapy in patients with more severe CKD (eGFR 15 mL/min/1.73 m2 to 44 mL/

min/1.73 m2 or with severe proteinuria).

About the Author

German T. Hernandez, MD , FASN, FACP, is an Associate Professor of Medicine in the Division of Nephrology & Hypertension and Biostatistics & Epidemiology at the Paul L. Foster School of Medicine, Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center in El Paso. He is the El Paso site principal investigator for many multicenter clinical trials. Dr. Hernandez received his medical degree at Harvard Medical School. He completed his postgraduate studies in internal medicine and nephrology as well as advanced

training in clinical research at the University of California, San Francisco.