Article

Psychotic Symptoms Spike Risk of Suicide Attempts in Teenagers

Author(s):

As the risk assessment of suicide attempts remains tremendously challenging due to the lack of clinical markers, researchers across five different countries studied the pathological significance of psychotic symptoms in terms of their influence on suicidal behavior.

As the risk assessment of suicide attempts remains tremendously challenging due to the lack of clinical markers, researchers across five different countries studied the pathological significance of psychotic symptoms in terms of their influence on suicidal behavior.

For their “Psychotic Symptoms and Population Risk for Suicide Attempt” prospective cohort study published online on July 17, 2013, in JAMA Psychiatry, Ian Kelleher, MD, PhD, from the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland, and investigators from Columbia University in New York City, the University of Molise in Italy, Maastricht University in the Netherlands, and the Karolinska Institutet in Sweden assessed 1,112 adolescent patients between the ages of 13 and 16 years old at baseline, three months, and 12 months for self-reported psychopathology, psychotic symptoms, and suicide attempts.

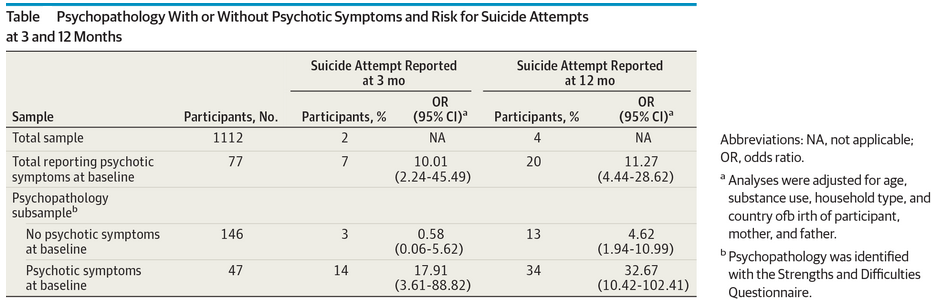

At baseline, 7 percent of the cohort reported psychotic symptoms of auditory hallucinations and delusions. Within that sample, 7 percent reported an attempt to commit suicide before the three-month follow-up assessment, compared to 1 percent of the patients who did not report psychotic symptoms at baseline, and by the 12-month follow-up, 20 percent had reported a suicide attempt, compared to 2.5 percent of the rest of the cohort. In a subsample of adolescents with psychopathology at baseline, 14 percent reported a suicide attempt before the three-month follow-up assessment, compared to 3 percent of the psychopathology patients who did not report psychotic symptoms at baseline, and by the one-year follow-up, 34 percent had reported a suicide attempt, compared to 13 percent of the remaining psychopathology cohort and 4 percent of the total general population — meaning “psychotic symptoms at both baseline and three-month follow-up were predictive of a 15-fold increased odds of suicide attempt between three- and 12-month follow-up,” the authors wrote. (Table)

“Participants with psychopathology who did not report psychotic symptoms did not have significantly increased odds of acute suicide attempts compared with the rest of the population. Those with psychopathology who did experience psychotic symptoms, on the other hand, had a nearly 70-fold increased odds of acute suicide attempts,” the researchers wrote. “In absolute terms, individuals with psychotic symptoms made up less than a quarter of the total group with psychopathology but accounted for nearly 80 percent of the acute suicide attempts in this group. Assuming a causative relationship for suicide attempts, the population-attributable fraction for psychotic symptoms would be 56 percent in the whole sample and 75 percent in the subsample with psychopathology.”

In light of those findings, the authors suggested that “careful assessment of psychotic symptoms — both attenuated and frank — in patients with nonpsychotic disorders … should be considered a key element of suicide risk assessment,” and “all future studies on suicidal behavior should incorporate a measure of psychotic symptoms.”