Publication

Article

Cardiology Review® Online

The YOGA My Heart Study

Ragavendra Baliga, MD, MBA, FACP, FRCP (Edin), FACC

Review

Lakkireddy D, Atkins D, Pillarisetti J, Ryschon K, et al. Effect of yoga on arrhythmia burden, anxiety, depression, and quality of life in paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: The YOGA My Heart Study.[published online January 25, 2013] J Am Coll Cardiol. pii: S0735-1097(13)00044-2. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2012.11.060.

The initiation and maintenance of atrial fibrillation (AF) is dependent on a variety of factors including cardiac autonomic function, depression, anxiety, and quality of life (QOL) factors.

Yoga involves exercise, breathing techniques, and meditation and is known to have beneficial effects on cardiovascular health. The mechanism for yoga’s positive effects on cardiovascular health probably involve modulating cardiac function, depression, anxiety, and QOL factors. The YOGA My Heart Study investigators, therefore, examined the effect of yoga on burden of AF, QOL, depression, and anxiety scores.

Study Details

This was a single-center prospective, self-controlled pre-post cohort study that enrolled 52 patients with symptomatic paroxysmal AF with an initial 3-month noninterventional observation period followed by twice-weekly 60-minute yoga training for the next 3 months. The participants were instructed to perform 10 minutes of pranayamas (deep abdominal breathing techniques), 10 minutes of warm-up exercises, 30 minutes of asanas (poses), and 10 minutes of relaxation exercises at each yoga session. The study investigators assessed AF episodes during the control and study periods as well as QOL scores using Short-Form 36 (SF-36), Zung self-rated anxiety, and Zung selfrated depression scores at baseline, before, and after the study phase in 49 patients (3 patients dropped out during the yoga phase of the study).

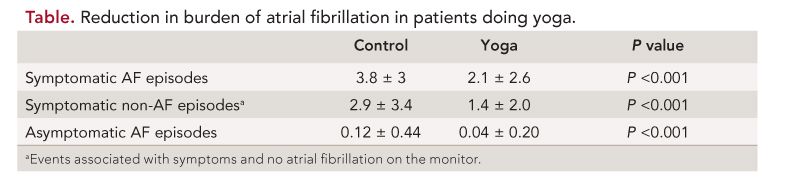

Fifty-three percent of the subjects were female; the mean age of study participants was 61 ± 11 years and mean body mass index was 28 ± 5.9 kg/m2. The mean duration of AF since diagnosis in this cohort was ~5 years with a mean left atrial size of 4.01 ± 0.5 cm and left ventricular ejection fraction of 59 ± 6%. The investigators found that yoga training reduced symptomatic AF episodes, symptomatic non- AF episodes, asymptomatic AF episodes, depression, and anxiety (P <0.001), and improved the QOL parameters of physical functioning, general health, vitality, social functioning, and mental health domains on the SF-36 (P = 0.017, P <0.001, P <0.001, P = 0.019, and P <0.001, respectively). The reduction in anxiety and depression scores did not correlate with reduction of AF burden. A total of 22% of the participants (n = 11) with AF during the control pre-yoga phase did not have an episode of AF during the yoga phase of the study. Investigators also found a significant decrease in heart rate and systolic and diastolic blood pressure before and after yoga (P <0.001). The decreases in heart rate may be related to a reduction in anxiety. The absolute changes in systolic blood pressure correlated with the reductions in burden of AF [symptomatic AF episodes (P = 0.03), asymptomatic AF episodes (P = 0.015), and symptomatic non-AF episodes (P = 0.04)], but also with anxiety scores (P = 0.04).

There was no correlation between the number of practice sessions and the primary and secondary outcomes of the study. Yoga was safe and well tolerated by the participants.

The authors concluded that in paroxysmal AF, yoga improves symptoms, arrhythmia burden of AF, heart rate, blood pressure, anxiety and depression scores, and QOL scores.

Commentary Emphasizing Both Body and Mind in Cardiovascular Disease

The American College of Cardiology, the American Heart Association, and the European Society of Cardiology guidelines recommend a simple classification based on the temporal progression of arrhythmia.1 The classification has 4 categories: first detected episode of AF; paroxysmal AF (self-terminating episodes lasting no longer than 7 days, commonly less than 24 hours); persistent AF (non-self-terminating episodes lasting more than 7 days, requiring electrical or pharmacologic cardioversion to terminate); and permanent AF (fails to terminate after cardioversion, or is accepted by the patient and the physician). Paroxysmal AF may be recurrent and is often progressive. Using the above definitions, a recent general-practice-based French study found that permanent AF accounted for 50% of cases, with 25% each for persistent and paroxysmal AF.2 Data from the Canadian Registry of Atrial Fibrillation (CARAF) suggest that among 757 patients with new-onset paroxysmal AF, approximately 8% to 9% may progress to permanent AF by the end of 1 year, a figure that increases to 25% by 5 years.3 Therefore, interventions to reduce the burden of paroxysmal AF should also reduce the burden of permanent AF.

Yoga has been shown to be beneficial to cardiovascular health.4,5 Its effects can potentially be attributed to the “placebo” effect or possibly the effect of “mind over matter.” Examples of the latter include the ability to walk on burning coals.6 Although yoga has been practiced in the East for centuries, it has not been completely integrated into allopathic medicine because of the paucity of randomized clinical trials7 to demonstrate its efficacy on cardiovascular health and an incomplete understanding of yoga’s mechanism of action. Yoga includes breathing exercises, exercise techniques, and meditation, and has been shown to favorably modulate autonomic function,8,9 stress,10 anxiety, depression, well-being, 11 and hypertension.12 In Sanskrit, “yoga” literally means “to make whole” or “to join,” and is an integral part of Ayurvedic medicine. It involves a series of poses: sequential slow movements (asanas) that are accompanied by deep abdominal breathing (pranayamas). The movements between poses are as important as maintaining a pose, and typically each pose is held for 4 or 5 breaths. The most popular styles of yoga include Anusara (characterized by free-flowing movements between poses termed vinyasa), Ashtanga (or power yoga), Bikram (performed in high-temperature rooms and thus best avoided by those with advanced cardiovascular disease), Hatha (which involves the practice of relaxing, restorative form; sometimes used as an encompassing term for all forms of yoga), and Iyengar yoga, which involves holding poses in strenuous positions for longer periods of time, such as headstands, and involves development of strength. In the study by Lakireddy et al, Iyengar yoga was used to reduce AF burden.

One of the notable findings of this study was that Iyengar yoga was associated with a ~5-mm fall in systolic blood pressure, which in turn reduced left atrial stretch/size13 and reduced the burden of paroxysmal AF.14 The reduction in blood pressure with yoga has been attributed to changes in neurohormonal mechanisms including the hypothalamus- pituitary axis and reductions in sympathetic activity, improvements in endothelial function, and improvements in inflammation of the vascular system. Although the study cohort was small, the findings suggest that yoga may be a useful adjunct, if not primary treatment, to reduce the burden of AF. Large multicenter trials are needed to confirm the findings of this path-finding study and to determine the predictors of response if indeed yoga reduces AF burden. This study also emphasizes the need to follow a holistic approach to cardiovascular disease—an emphasis on both the body and the mind. The mind is able to perform inexplicable events that modern medical science is unable to explain, and we must not be quick to discount these effects merely because we do not comprehend them. Therefore, mechanistic studies are also needed to determine how these work, and to show exactly how yoga reduces AF burden.

References

1. Fuster V, Ryden LE, Cannom DS, et al. ACC/ AHA/ESC 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation--executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2001 Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Atrial Fibrillation). Eur Heart J. 2006;27:1979-2030.

2. Levy S, Maarek M, Coumel P, et al. Characterization of different subsets of atrial fibrillation in general practice in France: the ALFA study. Circulation. 1999;99:3028-3035.

3. Kerr CR, Humphries KH, Talajic M, et al. Progression to chronic atrial fibrillation after the initial diagnosis of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: results from the Canadian Registry of Atrial Fibrillation. Am Heart J. 2005;149:489- 496.

4. Ornish D, Scherwitz LW, Billings JH, et al. Intensive lifestyle changes for reversal of coronary heart disease. JAMA. 1998;280:2001-2007. 5. Frishman WH, Grattan JG, Mamtani R. Alternative and complementary medical approaches in the prevention and treatment of cardiovascular disease. Curr Prob Cardiol. 2005;30:383-459.

6. Zipes DP. President’s page: complementary and alternative medicine: ignore at doctors’ and patients’ peril. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;37:2166-2169.

7. Lau HL, Kwong JS, Yeung F, Chau PH, Woo J. Yoga for secondary prevention of coronary heart disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;12: CD009506.

8. Bowman AJ, Clayton RH, Murray A, Reed JW, Subhan MM, Ford GA. Effects of aerobic exercise training and yoga on the baroreflex in healthy elderly persons. Eur J Clin Invest. 1997;27:443-449.

9. Khattab K, Khattab AA, Ortak J, Richardt G, Bonnemeier H. Iyengar yoga increases cardiac parasympathetic nervous modulation among healthy yoga practitioners. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2007;4:511-517. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nem087.

10. Michalsen A, Jeitler M, Brunnhuber S, et al. Iyengar yoga for distressed women: a 3-armed randomized controlled trial [published online September 25, 2012]. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 408727. doi: 10.1155/2012/408727.

11. Vogler J, O’Hara L, Gregg J, Burnell F. The impact of a short-term iyengar yoga program on the health and well-being of physically inactive older adults. Int J Yoga Ther. 2011;21:61-72.

12. Cohen DL, Bloedon LT, Rothman RL, et al. Iyengar yoga versus enhanced usual care on blood pressure in patients with prehypertension to stage I hypertension: a randomized controlled trial [published online February 14, 2011]. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. doi:10.1093/ ecam/nep130.

13. Tsang TS, Barnes ME, Bailey KR, et al. Left atrial volume: important risk marker of incident atrial fibrillation in 1655 older men and women. Mayo Clin Proc. 2001;76:467-475.

14. Grundvold I, Skretteberg PT, Liestol K, et al. Upper normal blood pressures predict incident atrial fibrillation in healthy middle-aged men: a 35-year follow-up study. Hypertension. 2012;59:198-204.

About the Author

Ragavendra Baliga, MD, MBA, FACP, FRCP (Edin), FACC, is Chief Mentor Officer for Clinical Faculty and Associate- Chief/Associate Division Director, Division of Cardiovascular Medicine, Wexner Medical Center, and Professor of Internal Medicine at The Ohio State University in Columbus. He received his MD from St. John’s Medical College in Bangalore, India, and completed his internal medicine residency at Victoria Hospital in Bangalore. He completed his cardiology fellowship at Hammersmith Hospital, London, UK, and advanced fellowships at Brigham & Women’s Hospital/Harvard Medical School, Boston University Medical Center, and UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX. He is board certified in internal medicine, cardiovascular diseases, and advanced heart failure and cardiac transplantation. He was a faculty cardiologist at the University of Michigan and received an MBA from the Stephen Ross School of Business. Dr Baliga joined The Ohio State University in 2005.