Article

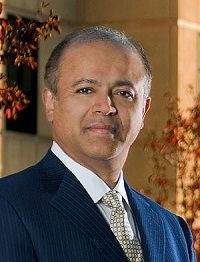

Verghese: Patients Have Two Hearts

Author(s):

Medicine is far more than a science. Physicians should never forget that their patients are more than collections of data and that care is not measured in mouse clicks, physician-author, educator and bedside manner expert extraordinaire Abraham Verghese, MD, told a standing room crowd. His talk "I Carry Your Heart" kicked off the American College of Cardiology's meeting in San Diego, CA.

There is curing, and then there is healing.

Kicking off the American College of Cardiology 64th Annual Scientific Session and Expo in San Diego, CA, physician author Abraham Verghese, MD, MACP, MFA brought his message of compassionate care and human connection to a standing-room only crowd.

The meeting has drawn about 20,000 attendees from 130 nations and all 50 states.

Verghese, whose non-fiction book My Own Country: a Doctor’s Story, and novel Cutting for Stone are based on both the drama and emotional aspects of practicing medicine urged his listeners to always be aware of the powerful connection they can—and should—have with patients.

He fears that technology and the ever-growing emphasis on big data and keeping up with science can break that bond.

For instance, he said, electronic medical records do little for helping physicians and patients and steal precious time.

“Emergency room physicians spend 46% of their day on the computer,” he said, “It takes 9 clicks to order an aspirin—probably twice that if you order half strength aspirin—197 clicks to admit a patient.”

The purpose of electronic records is to make billing accurate, he said, not to improve the near-mystic relationship a physician should have with a patient, particularly one who is seriously ill.

In the practice of cardiology, he said, physicians should never forget that the patient has “two hearts” one that is the subject of tests and images, and one that holds the patient’s soul.

When he first meets a patient, he said, the encounter has all the aspects of an ancient ritual.

His white coat is “a shaman-istic garment” with its pockets full of magical instruments. Meanwhile the patient is in a flimsy paper gown, and surrenders to trust in allowing the doctor to examine him.

“Patients are telling me secrets,” he said.

Finding the right words to talk to seriously ill patients is always difficult he said, and physicians are often either forthright or come off as “mushy” relying on platitudes and banalities.

“This is a place beyond words,” he said, and physicians who care for these patients should never forget about their “real” hearts, not the organ of muscle, blood, and nerves that modern medicine tracks so well.

Find a way to communicate to patients “I carry your heart,” he said.

Verghese was born to parents who migrated to Addis Ababa, Ethiopia from India but had to flee after Emperor Haile Selassie was deposed. He joined them in the US, working as a hospital orderly then traveling to Madras, India to become a physician. He returned to the US and worked in a municipal hospital in Boston, MA, and was on the frontlines as the then baffling illness that turned out to be AIDS was just starting to appear.

He became an infectious disease specialist, but as foreign medical graduate, the best job he could find was in an underserved community in rural Tennessee.

Those experiences became the basis for his non-fiction book, My Own Country: a Doctor’s Story. His novel is set in Ethiopia during the fall of Selassie and later in a New York City hospital.

Verghese is a professor of the theory and practice medicine at Stanford University School of Medicine.