News

Article

Women Experience Worse Mental Health, Burnout Than Men

Author(s):

In an interview with HCPLive, Viktoriya Karakcheyeva, MD, discussed how women healthcare workers experience more burnout than their male colleagues.

Viktoriya Karakcheyeva, MD, MS, NCC, LCP-SP, LCADAS

Credit: GW Resiliency & Well-Being Center at the George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences

Even though women have more rights today than a hundred years ago, women healthcare workers today still experience inequality in the workplace—from unequal pay to some patients refusing to address them by the doctor title but only by their first name, unlike their male colleagues.

Because of these inequities, females working in healthcare face significantly more stress and burnout than male coworkers, according to a new study led by Viktoriya Karakcheyeva, MD, MS, NCC, LCP-SP, LCADAS, from the GW Resiliency & Well-Being Center at the George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences.1,2

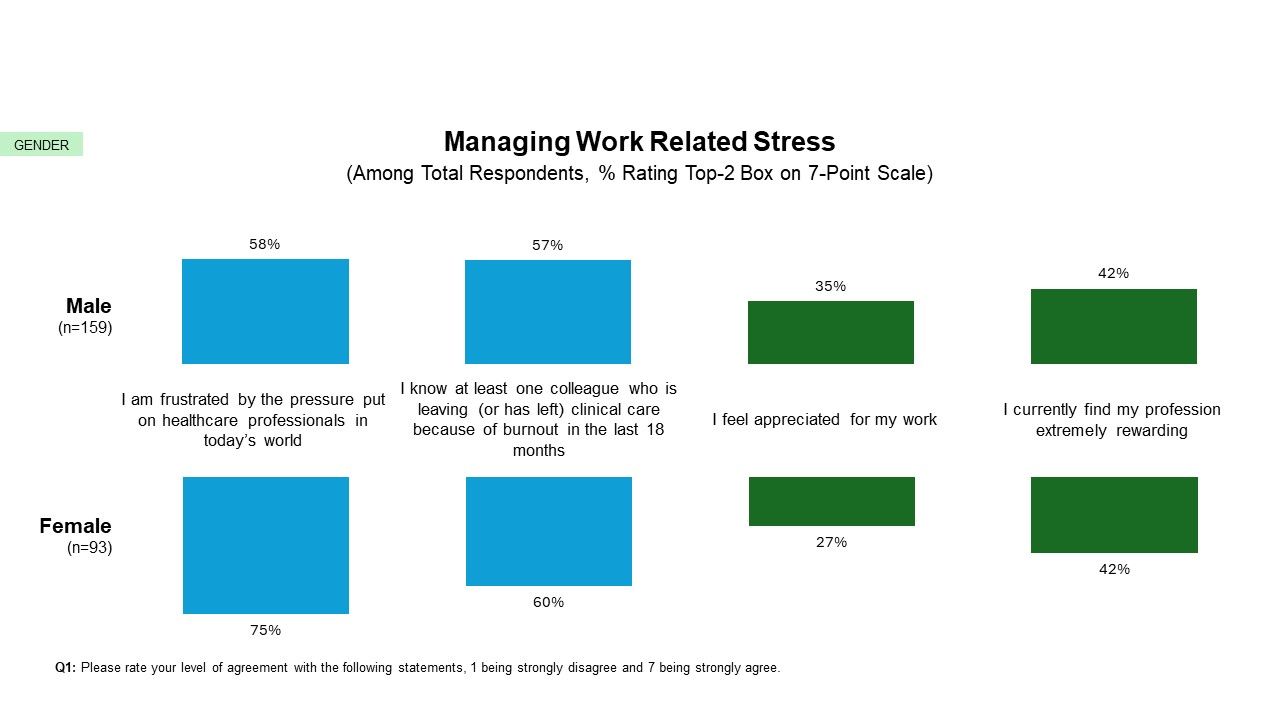

A new InCrowd report found although US physician burnout reduced to 64% in 2023 from 70% in 2022, the rate is still significantly greater than in 2021 (47%).3 Additionally, the report showed more females (75%) feel frustrated by the pressure on healthcare professionals than males (58%).4

An InCrowd report found females tend to feel being more frustrated by the pressure on healthcare professionals than males.

Credit: InCrowd, an Apollo Intelligence brand

Primary factors associated with burnout among female workers included women having poor work-life integration and balance, having less professional autonomy than their male colleagues, and structural gender discrimination. Women with poor work-life balance report struggling to create boundaries between their personal and professional identities. They may feel pressured to meet societal caregiver expectations.

Karakcheyeva told HCPLive she and her team found a phenomenon labeled as the “motherhood penalty” in their research, which was a significant cause of burnout among women.

“Women who take time away from their careers to have families often experience negative repercussions upon reentering the workforce such as fewer opportunities for promotion, the unfair view that women put their family before their careers, and the ongoing expectation that women must act as caregivers to the determent of their other identifies,” she said.

Fortunately, interventions can reduce harmful stress, promote job satisfaction, and improve work-life balance. Interventions include flexible work schedules, expanded parental leave policies, professional development opportunities during the regular workday, and opportunities for professional recognition. Approximately 21% of the reviewed studies found the importance of supportive personal relationships in the workplace.

“Effective mentorship programs can help women develop a greater sense of belonging in the workplace, build deeper connections with other women in leadership roles, and ultimately show improvement toward overall job satisfaction,” Karakcheyeva said.

The greater stress and burnout of women compared to men does not only apply to the healthcare field. A recent Kaiser Family Foundation survey found a greater number of women (50%) thought they needed mental health services in the past 2 years than men (35%).5 On average, women in Pennsylvania reported 5.3 poor mental health days a month, which is above the national average of 4.2 days.6

Additionally, the survey found women are more likely to seek care for mental health issues compared to men.3

“[As] a psychiatrist, we know that women tend to reach out and seek care more because of the stressors in their lives and their struggle between balancing things and balancing work and home,” Emily Bernstein, MD, from Rittenhouse Psychiatric Associates, told HCPLive. “For whatever reason, there seems to be women [who] feel more comfortable reaching out for help than men still.”

Women in different age groups have variations in mental health outcomes. For instance, younger women aged 18 – 25 years reported poorer mental challenges than women aged 50 – 64 years.

“That was a little surprising for me,” Bernstein said.

She believes the reason behind the variations in mental health for different age groups is due to COVID-19. For younger women, they had incredibly high environmental stressors with disrupted schooling and social lives, creating loneliness. Those young adult years are when people tend to figure out their sense of self, and COVID-19 interfering with that stage could have affected mental health.

Additionally, after COVID-19, a lot of jobs became either remote or hybrid, which prevents people from going into the office and interacting with coworkers.

“It’s like a double-edged sword,” Bernstein said. “It's great for flexibility, but I think that age group that 18 to 25, age group, people are just feeling very, very isolated and alone and not having a community of work or school.”

The survey found 10% of women who felt that they needed mental health services were unable to secure an appointment in the past 2 years, and 40% simply did not seek care. Bernstein explained how access to mental health care depends on the number of providers where you live. Other barriers include providers not taking their insurance or the time commitment when balancing work and taking care of a family.

However, Bernstein pointed out the one good thing to come out of the pandemic: Telehealth. Virtual health appointments increase access to care, and 60% of women had a telehealth appointment in the past 2 years.

“People living in underserved areas are able to access care via telehealth as opposed to driving an hour or 2 hours even to find a provider,” Bernstein said. “So that's been an amazing thing.”

Many women may have poor mental health, but fortunately, there are ways to alleviate their well-being. For instance, improving sleep quality, physical activity, and nutrition can alleviate burnout and well-being.1

Research has found intentional mindfulness, nutrition, exercise, and restorative sleep may reduce compassion fatigue, stress, and burnout. Going back to burnout female healthcare workers, these methods can help improve their well-being as well.

“The challenge is in cultivating work environments that both recognize the importance of these good sleep, physical activity, nutrition, and self-care and actively provide outlets or opportunities for individuals to attend to these needs,” Karakcheyeva said.

References

- Karakcheyeva V, Willis-Johnson H, Corr PG, Frame LA. The Well-Being of Women in Healthcare Professions: A Comprehensive Review. Glob Adv Integr Med Health. 2024;13:27536130241232929. Published 2024 Feb 10. doi:10.1177/27536130241232929

- Derman, C. Women Working in Healthcare Have Significantly More Burnout Than Men Colleagues. HCPLive. February 23, 2024. https://www.hcplive.com/view/women-working-healthcare-have-significantly-more-burnouts-than-men-colleagues. Accessed March 7, 2024.

- US Physicians Burnout Data Show That Quality of Care, Physician Retention Continue To Be A Concern, While US Physician Burnout Declines Slightly In 2023, Says Incrowd Report. Business Wire. March 3, 2024. https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20240305438401/en/US-Physician-Burnout-Data-Show-That-Quality-of-Care-Physician-Retention-Continue-to-be-a-Concern-while-US-Physician-Burnout-Declines-Slightly-in-2023-says-InCrowd-Report#:~:text=US%20physician%20burnout%20declined%20slightly,issues%2C%20says%20InCrowd%20burnout%20report. Accessed March 7, 2024.

- DeMonto, R. Knowing Your Audience: Physician Engagement in a Time of Accelerated Professional Burnout. InCrowd. February 7, 2024. https://incrowdnow.com/resources/physician-burnout-knowing-your-audience Accessed March 7, 2024

- Diep, K, Frederiksen, B, Long, M, et al. Access and Coverage for Mental Health Care: Findings from the 2022 KFF Women’s Health Survey. Kaiser Family Foundation. December 20, 2022. https://www.kff.org/womens-health-policy/issue-brief/access-and-coverage-for-mental-health-care-findings-from-the-2022-kff-womens-health-survey/?. Accessed March 7, 2024.

- Pennsylvania Women’s Health Status Data. Kaiser Family Foundation. https://www.kff.org/interactive/womens-health-profiles/pennsylvania/health-status..Accessed March 7, 2024.