Publication

Article

Family Practice Recertification

75-Year-Old Man with a History of Single-chamber Pacemaker Presents with Dizziness and Nausea

Author(s):

A 75 year-old man with a history of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation and a single-chamber pacemaker placed for bradycardia 5 years prior presents with dizziness and nausea to clinic. He notes that he has also been feeling short of breath with normal activities of daily living.

A 75 year-old man with a history of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation and a single-chamber pacemaker placed for bradycardia 5 years prior presents with dizziness and nausea to clinic. He notes that he has also been feeling short of breath with normal activities of daily living. He has no other symptoms of angina or heart failure. His heart rate is about 40 beats per minute and his blood pressure is 150/90 mmHg.

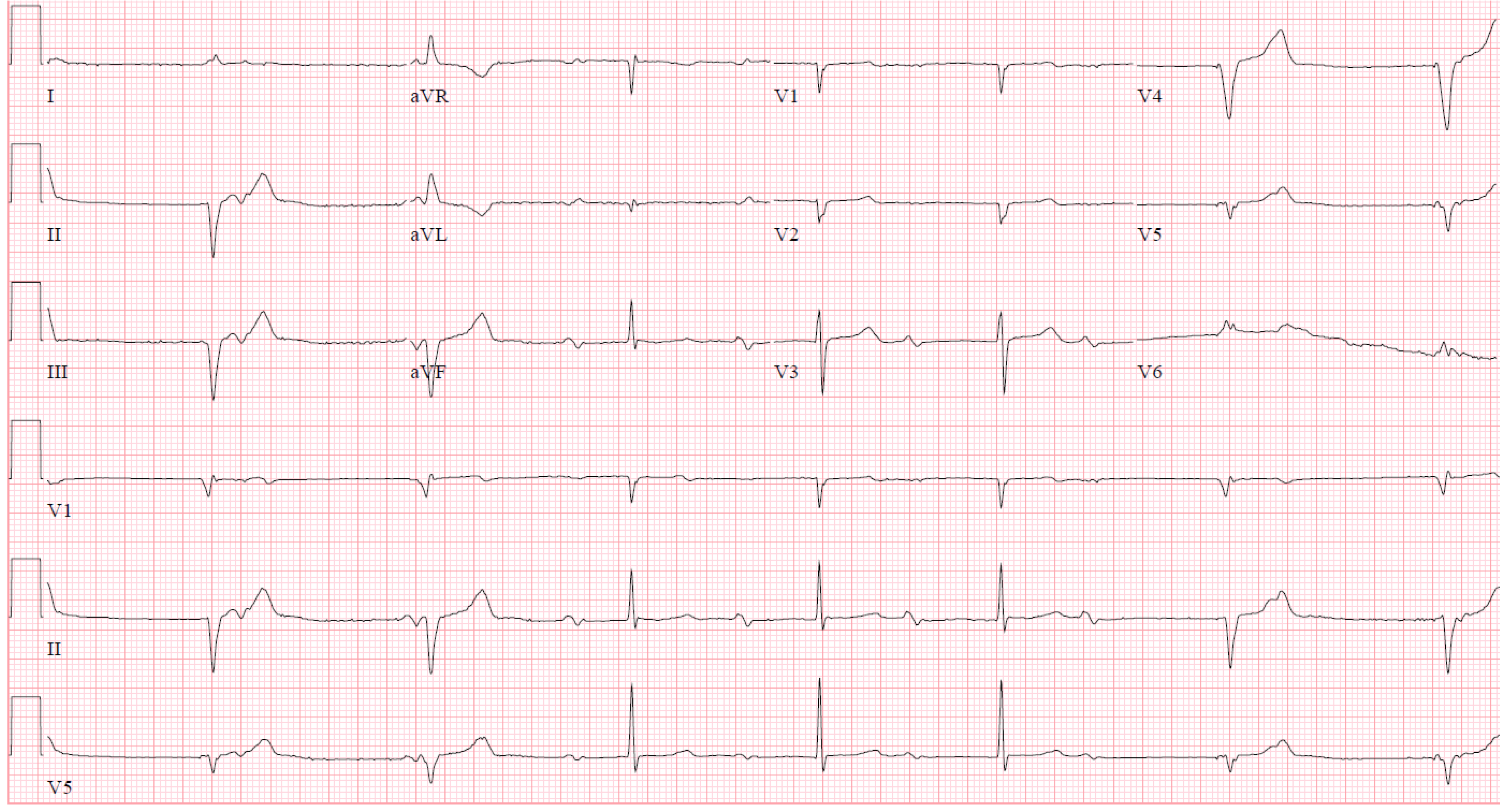

On exam, he appears in no distress. On auscultation, S1 sounds variable in intensity. Although the rate is slow, the rhythm appears regular. His lungs are clear to auscultation. His JVP is not elevated consistently. However, there is an intermittent pulsation in the neck. An EKG is performed in the office and is shown below.

Figure 1

The EKG demonstrates a bradycardia with both narrow complexes and wide complexes. When facing multiple types of QRS morphologies, look for the most normal first and characterize the rhythm in that section. It will often provide clues to the rest of the EKG.

P waves are present before each of the narrow QRS complexes. However, the interval from the P to the QRS is significantly prolonged and appears progressive from the 3rd QRS to the 6th QRS complex. It has the appearance of a second degree AV block Mobitz Type 1, or Wenckebach pattern.

There are no dropped beats, or QRS complexes, due to the presence of the pacemaker. The P waves in the initial portion of the EKG are buried in the paced ventricular beats. They cannot conduct into the ventricle because the ventricle is refractory at that time. The pacemaker is not inhibited by the presence of the P waves because a single-lead ventricular pacemaker cannot sense activity in the atria.

When looking at this EKG, one might mistake this EKG for having complete heart block due to the intermittent wide complex QRS morphology and the seemingly incessant marching of the P wave. Despite the lack of large pacing spikes, there are clues to pacemaker activity. The left bundle appearing morphology, the superiorly directed QRS complexes (down-going in the inferior leads) and the fact that the complex comes in late, support these as being ventricularly paced complexes coming from the RV apex. If able to inspect closely, there are very small pacemaker artifact spikes before the QRS. They are most easily identified in V4 but also identifiable in other leads.

Pacemaker leads can be unipolar or bipolar. Unipolar leads create the familiar large pacing spike on the ECG as the impulse flows through the leads tip (cathode) and back to the impulse generator (anode). Bipolar leads can have nearly invisible pacemaker spikes as the impulse flows through the leads tip (cathode) and back to a slightly more proximal portion on the lead where the anode is placed. Bipolar leads are less susceptible to being inhibited by overlying myopotentials, but are a little thicker than unipolar leads.

Single-chamber pacemakers are used less often, in favor of dual-chamber pacemakers systems, which attempt to retain AV synchrony. But single-chamber pacemakers are still indicated in certain clinical situations. If there is no need to retain AV synchrony, as in chronic atrial fibrillation or atrial tachyarrhythmia, than a single lead in the ventricle that never sees the activity in the atrium may be appropriate.

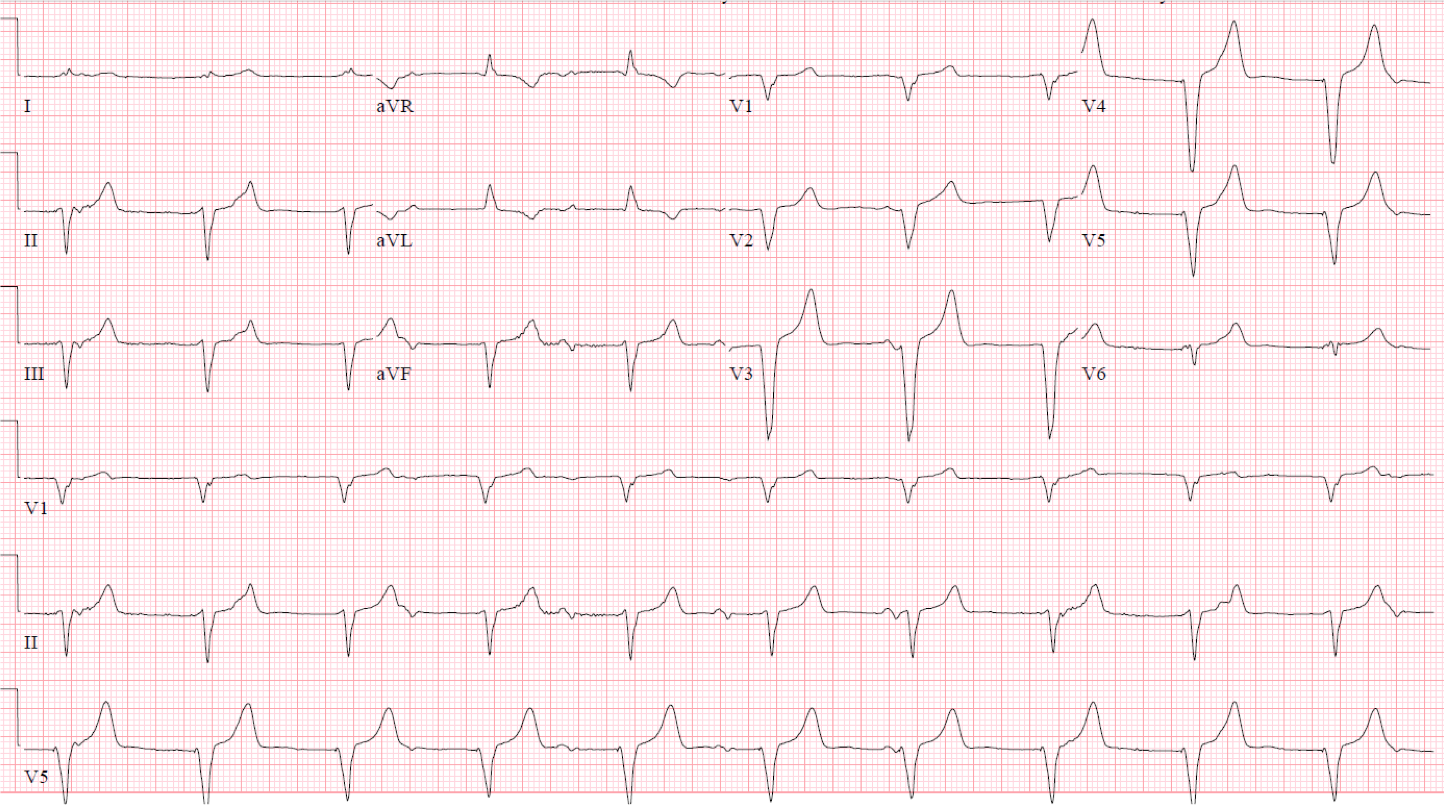

In order to quickly alleviate the patient’s symptoms, the lower rate limit for the pacemaker was increased from 40 bpm to 60 bpm. His follow-up EKG is shown below and demonstrates AV dyssynchrony with a competing atrial rhythm and ventricularly paced rhythm.

Figure 2

The pulsations in the patient’s neck worsened and demonstrate an example of cannon atrial waves, which can often be seen in AV dyssynchrony when the atrium contract against a closed tricuspid valve. Ultimately, the patient was scheduled for placement of an atrial lead and upgrade to dual-chamber pacemaker. Once he had a pacemaker that allowed maintenance of AV synchrony and rate responsiveness, his symptoms resolved and exertional capacity returned to normal.

1. Epstein AE, DiMarco JP, Ellenbogen KA, et al. ACC/AHA/HRS 2008 Guidelines for Device-Based Therapy of Cardiac Rhythm Abnormalities: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the ACC/AHA/NASPE 2002 Guideline Update for Implantation of Cardiac Pacemakers and Antiarrhythmia Devices): developed in collaboration with the American Association for Thoracic Surgery and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Circulation 2008; 117:e350.

2. Gregaratos G et al. ACC/AHA Guidelines for Implantation of Cardiac Pacemakers and Antiarrhythmia Devices: Executive Summary—a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. (Committee on Pacemaker Implantation). Circulation. 1998; 97(13):1325-35

3. Josephson, ME. Atrioventricular Conduction. In: Clinical Cardiac Electrophysiology, 4th, Lippincott, Philadelphia 2008. p.93

About the AuthorDaniel R. Schimmel, MD MS is an interventional cardiologist at Northwestern Memorial Hospital and assistant professor at the Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine. His clinical interests include acute cardiac care, coronary and peripheral interventions, structural heart disease, venothromboembolic disease and cardiovascular imaging. Having been a chief resident and chief fellow at Northwestern University he is dedicated to education with a research focus in simulation-based medical education. During his training years, Dr. Schimmel was recognized several times with the Excellence in Teaching Award. He also obtained his Master’s of Science in Clinical Investigation from Northwestern University and a certificate in quality and safety improvement.