Publication

Article

Family Practice Recertification

A Baseball Player with Right Wrist Pain

Author(s):

Though a diagnosis can be made from a single plain X-ray film, multiple views are often recommended, especially when the anatomy is so small that it is difficult to visualize a fracture.

James D. Collins, MD

This 22-year-old right-handed male baseball player was injured while running to home plate. He slid with the palm of his right hand down and his right foot under the right hip, with the left leg extended forward. After colliding with the catcher, he complained of dizziness and pain over the right wrist. The team physician obtained vital signs, including a blood pressure of 120/80, a respiration of 17/min, and a pulse of 72 bpm.

The patient was then transferred to the emergency room for X-rays focusing over the swollen right wrist.

Radiographic Findings

The patient’s posterior-anterior (PA) lateral radiographs with right and left oblique views of the right hand and wrist displayed soft tissue swelling at the base of the right thumb in close proximity to the right scaphoid bone.1-2 This finding suggested a right scaphoid bone fracture; however, initial X-rays in the emergency room revealed no definitive evidence of fracture.

An X-ray only displays 70% of the anatomic structures because 30% of the beam is absorbed by vascular, osseous, and soft tissue. Therefore, the images selected for this display were enlarged and inverted to best display the patient’s landmark anatomy.

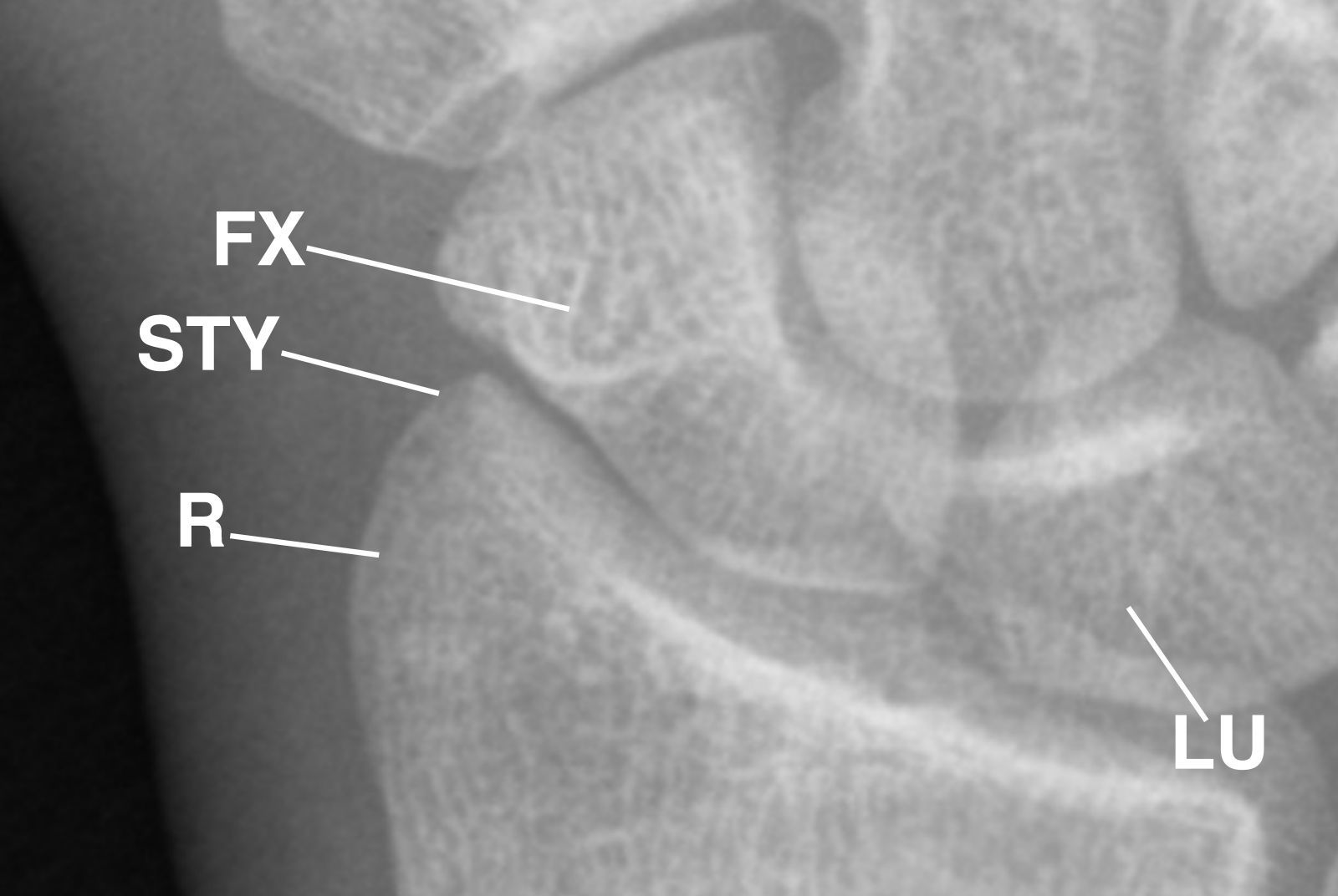

The enlarged dorsopalmar radiograph of the right wrist (Figure 1) displayed a disruption in the trabeculae of the right scaphoid bone, reflecting a fracture site.

Figure 1 This enlarged dorsopalmar radiograph of the right wrist displays the disrupted trabeculae of the right scaphoid bone, reflecting the fracture site. FX= fracture; R= radius bone; STY= styloid process of the radius;

LU= lunate bone.

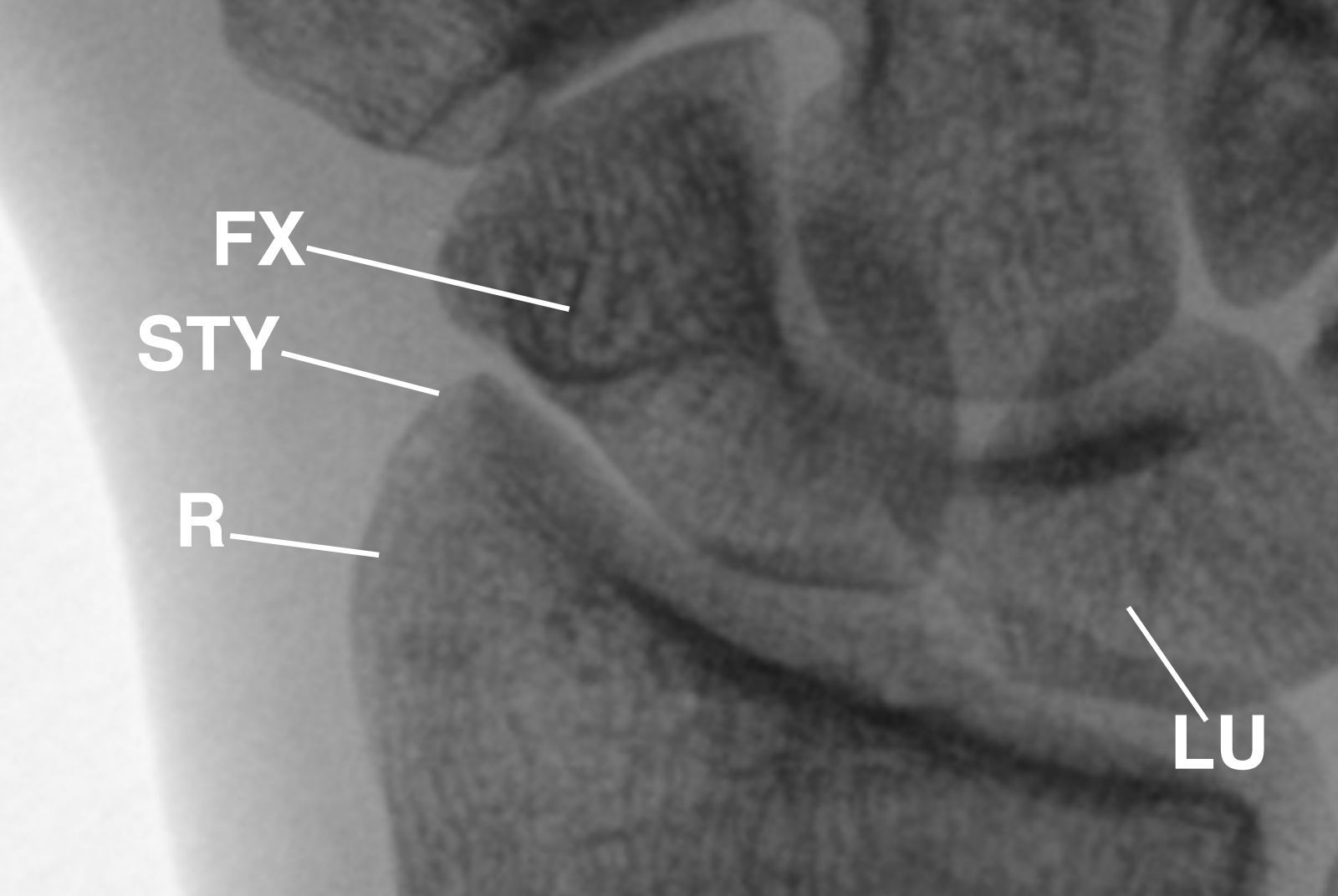

This image was inverted (Figure 2) to provide a different perspective of the enlarged dorsopalmar radiograph of the right wrist, which better displayed the fractured trabeculae of the right scaphoid bone.

This inverted image provides a different perspective of the enlarged dorsopalmar radiograph of the right wrist displayed in Figure 1.

Figure 2

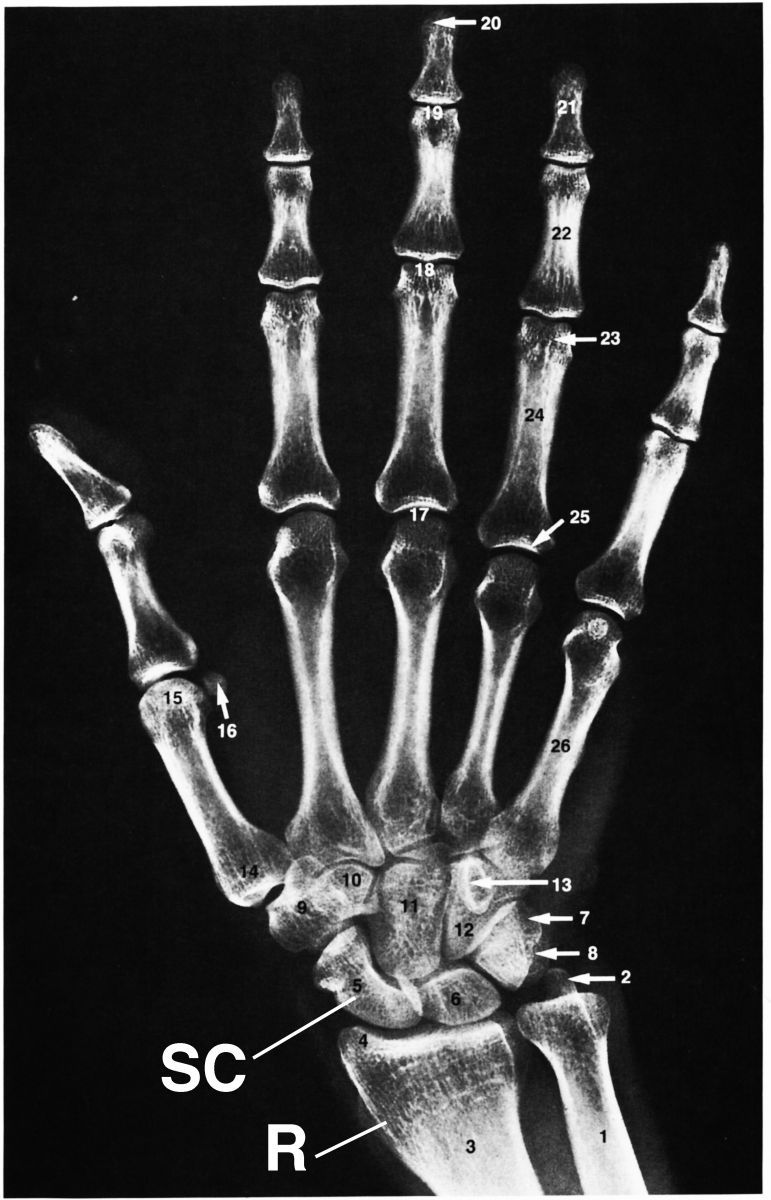

To better appreciate the fracture, the images were compared to a normal X-ray of a right wrist and hand (Figure 3).

This dorsopalmar radiograph of the right wrist and hand displays normal landmark anatomy. The image was obtained from Anatomy: A Regional Atlas of the Human Body (5th ed.) with permission from Carmine D. Clemente. Observe the scaphoid bone (SC) and radius for landmarks.

Figure 3

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be required to display the landmark anatomy of vascular, osseous, and soft tissues, and thus, the fracture. However, an MRI was suggested but not obtained in this patient.

Discussion

The scaphoid bone is one of the smallest bones in the wrist. It is located on the thumb side, in the area where the wrist bends. Though it is the most commonly fractured carpal bone, it is often overlooked, particularly if the oblique and special views of the scaphoid bone are omitted.

A scaphoid fracture is typically caused by falling with an outstretched hand and landing with the weight on the palm.2 The end of 1 of the forearm bones may also break during this type of fall, depending on the position of the hand on landing.

Scaphoid fractures can occur among people of all ages, though men aged 20-30 years old are most likely to experience them. The injury often takes place during sports activities or motor vehicle accidents, and there are no specific risks or diseases that increase its odds of occurrence.

Scaphoid fractures usually cause pain and swelling at the base of the thumb. The pain may be severe when the patient moves his or her thumb or wrist, or tries to grip something. Any pain in the wrist that does not go away within 24 hours of the injury may signal a fracture, which usually causes the patient to see a physician.

X-rays may display a space within the scaphoid bone, but sometimes, a fracture is not apparent on the X-ray at the time of imaging.3 If this is the case, the physician may put the wrist in a cast for 1-2 weeks.

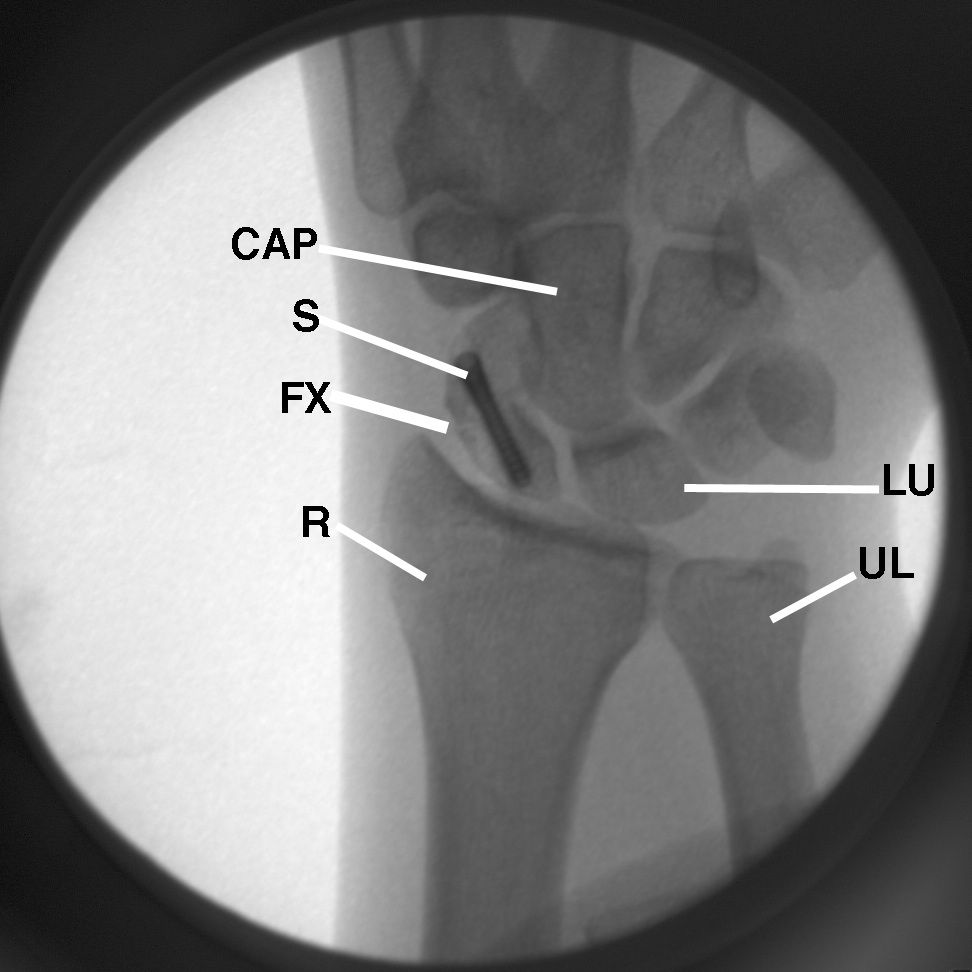

In this patient, a cast was placed around the right wrist (Figure 4) to stabilize the hand over a 2-week waiting period, and heavy lifting was not recommended.

Figure 4 This is a dorsopalmar radiograph of the right wrist in a cast that includes the elbow (not displayed) post-fixation. CAP= capitate bone;

UL= ulna bone

.

After 2 weeks, a repeat x-ray was obtained and displayed a fracture of the distal scaphoid. A small screw was surgically placed to fixate the right scaphoid bone in place until it fully healed (Figure 5).

Figure 5 This inverted dorsopalmar enlarged image shows the post-surgical placement of a small screw (S) to hold the right scaphoid in place until the bone is fully healed. Observe the separation of the fracture site.

Take-Home Message

Annotated landmark anatomy plays a crucial role in making an accurate diagnosis. Though a diagnosis can be made from a single plain X-ray film, multiple views are often recommended, especially when the anatomy is so small that it is difficult to visualize a fracture, as it was in this case. Osseous and soft tissues are not well displayed on X-rays because the tissue absorbs 30% of the beam, leaving 70% of the beam responsible for the image displayed. Therefore, the images were enlarged and inverted to provide a different perspective of the trabeculae within the scaphoid bone and best display the fracture site.

References

1. Kohler A. (1968). Borderlands of the Normal Early Pathologic Changes in Skeletal Roentgenology (3rd ed.). New York: Grune & Stratton.

2. Clemente CD. (2007). Anatomy: A Regional Atlas of the Human Body (5th ed.). Baltimore: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins.

3. Meschan I. (1966). Roentgen Signs in Clinical Practice: Vol. 1. Basic Principles and Radiology of the Skeletal System. Philadelphia: Saunders.

About the Author

James D. Collins, MD, is Professor and General Radiologist in the Department of Radiology at the UCLA David Geffen School Medicine. He formerly served as Director of the required medical student training for the department and President of the James T. Case Radiologic Foundation. Collins has an extensive background of publications, consultations, and editorial positions, including his current post as the Radiology Editor for the Journal of the National Medical Association. He specializes in bilateral 3-dimensional MRI and MRA imaging of the brachial plexus and has been performing those studies since 1985.