Publication

Article

Family Practice Recertification

A Middle-Aged Man with Exertional Hemoptysis

Author(s):

A middle-aged man presents with exertional hemoptysis to your clinic. There is no associated chest discomfort with activity. At rest, he has no complaints. His exam is significant for a normal HR and BP and a normal lung exam. His cardiac exam is notable for a gallop. No murmurs are appreciated. A pulmonary evaluation including PFTs and CT PE protocol are negative.

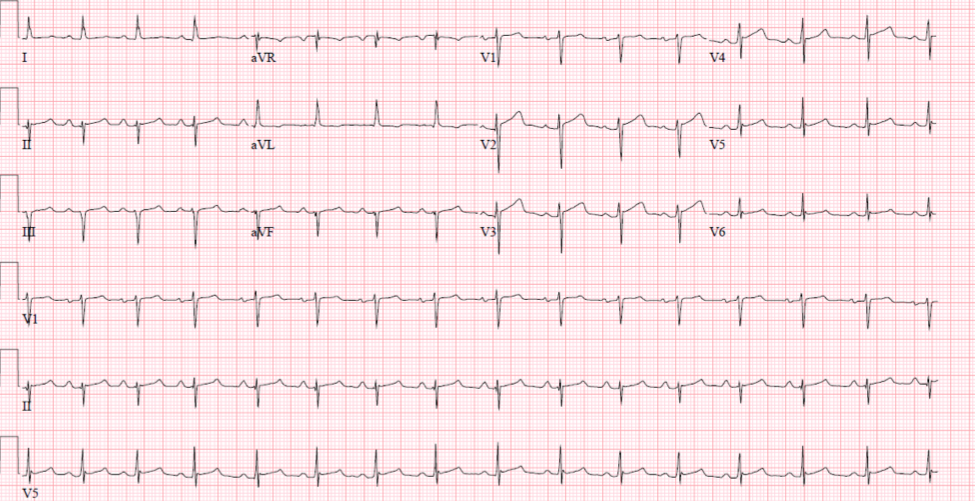

A middle-aged man presents with exertional hemoptysis to your clinic. There is no associated chest discomfort with activity. At rest, he has no complaints. His exam is significant for a normal HR and BP and a normal lung exam. His cardiac exam is notable for a gallop. No murmurs are appreciated. A pulmonary evaluation including PFTs and CT PE protocol are negative. An EKG is performed in the office and is shown below.

The EKG demonstrates a normal rhythm with a rate of approximately 95 bpm. There are nonspecific concave ST segment elevations in the precordial leads. His ECG is also notable for a left anterior fascicular block (LAFB).

The diagnosis of LAFB is made when left axis deviation is present with a qR in lead aVL and a QRS duration less than 120ms.

The quick way to check axis is to see upright QRS depolarization in both leads I and aVF, suggesting depolarization is moving in an imaginary line from the right shoulder to the left foot. Left axis deviation should be suspected if the QRS in lead I is upright and is down-going in aVF. To confirm left axis deviation, look to lead II. If lead II is mostly down-going (while upright in lead I and down-going in aVF), the overall depolarization falls in the -45 to -90 frontal plane, consistent with left axis deviation. This would be an imaginary line drawn from the feet to the left shoulder or straight to the head.

The left anterior fascicle branches anteriorly away from the main body of the left bundle. It crosses anteriorly in the left ventricular outflow tract. Because of this course, it is more sensitive to the long-term effects of elevated pressure and increased flow through the aortic valve. It is also subject to conditions causing septal ischemia.

The most common cause of LAFB is coronary artery disease and a frequent association with anteroseptal or anterolateral myocardial infarction (MI). The second most common cause is systemic arterial hypertension followed by cardiomyopathies and infiltrative or fibrotic disorders. LAFB can also occur in aortic valvular disease, congenital cardiomyopathies and post-cardiac surgery.

The differential diagnosis of LAFB contains other causes of left axis deviation. These include but are not limited to a horizontally rotated heart, isolated left ventricular hypertrophy, Wolff-Parkinson-White pattern, inferolateral MI and hypertrophic subaortic stenosis.

The significance of LAFB in the absence of evident cardiac disease is unknown. Most studies suggest incidental LAFB has no clinical significance, although one relatively recent study from the

Cardiovascular Health Study with median follow-up of 15.7 years suggested an increased mortality with lone LAFB.

However, the addition of LAFB to evident cardiovascular disease has been shown to be a negative prognostic factor with an increase in cardiovascular mortality. Interestingly, although LAFB is a conduction defect, it is not considered a precursor to complete heart block or an increased need for future pacemaker.

Returning to our patient, an echocardiogram revealed severe left ventricular hypertrophy that was out of proportion to the voltage seen on the above ECG. The finding of severe left ventricular hypertrophy in the absence of a hypertensive history, with normal voltage on ECG should prompt one to consider infiltrative cardiomyopathies. A cardiac MRI demonstrated diffuse microscopic fibrosis. The LAFB was likely a sequelae of fibrotic involvement of the septum, interrupting the left anterior fascicle.

A cardiac biopsy was performed which demonstrated AL cardiac amyloidosis. A right heart catheterization revealed normal resting pressures that became severely elevated within one minute of exercise. His hemoptysis during exertion was due to severe diastolic dysfunction that prevented the left ventricle from accepting the increased venous return with exercise.

If LAFB is found incidentally as part of a screening in the outpatient setting, with a completely negative history and exam for cardiac disease, there may not be a negative prognostic implication.

The finding of LAFB in a patient with cardiopulmonary symptoms should prompt investigation with an echocardiogram and consideration of an ischemic evaluation. If LAFB is found in a patient with known cardiac disease, it may serve to identify increased cardiovascular risk.

Diagnosis of LAFB

1. Frontal plane axis of -45 to -90

2. qR pattern in aVL

3. QRS duration less than 120 ms

4. Time to peak of R in aVL of 45 ms or more

Other common findings

1. qR pattern in I, V5,V6

2. rS pattern in II, III and aVF

References

1. Mandyam MC, Soliman EZ, Heckbert SR, Vittinghoff E, Marcus GM. Long-term outcomes of left anterior fascicular block in the absence of overt cardiovascular disease. JAMA: the journal of the American Medical Association. 2013;309(15):1587—1588.

2. Elizari MV, Acunzo RS, Ferreiro M. Hemiblocks revisited. Circulation. 2007;115(9):1154—1163.

About the AuthorDaniel R. Schimmel, MD MS is an interventional cardiologist at Northwestern Memorial Hospital and assistant professor at the Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine. His clinical interests include acute cardiac care, coronary and peripheral interventions, structural heart disease, venothromboembolic disease and cardiovascular imaging. Having been a chief resident and chief fellow at Northwestern University he is dedicated to education with a research focus in simulation-based medical education. During his training years, Dr. Schimmel was recognized several times with the Excellence in Teaching Award. He also obtained his Master’s of Science in Clinical Investigation from Northwestern University and a certificate in quality and safety improvement.