Publication

Article

Family Practice Recertification

Clinical Photos Often Captured on Smartphones without Consent

Author(s):

Although many physicians currently snap, store, and share clinical photographs on their smartphones, they often neglect to ask patients for permission to do so.

Although many physicians currently snap, store, and share clinical photographs on their smartphones, they often neglect to ask patients for permission to do so, a study published in the July 2014 issue of the Journal of Mobile Technology in Medicine has found.

“Smartphones have evolved to the point that they now routinely integrate a digital camera of an acceptable clinical quality capable of capturing medical images,” Michael Kirk, MBBS, and his colleagues noted in the study. “This rapid evolution of technology creates the potential to enhance the clinical care of patients … but also brings with it issues of confidentiality, privacy, and policy control.”

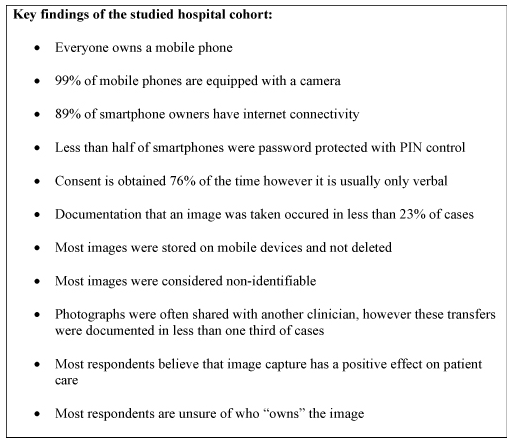

To assess physicians’ perceptions regarding “issues surrounding the recording and dissemination of medical images using smartphones,” the study authors invited all clinicians and medical students at a metropolitan hospital in Melbourne, Australia, to participate in an online survey on the topic. According to the researchers, the majority of the resulting 134 (32%) responses came from the surgical discipline (45%), followed by medicine (22%), emergency medicine (20%), critical care (7%), and pediatrics (6%). All but one respondent owned a mobile phone equipped with a camera, the authors said.

The survey results indicated that nearly two-thirds (65%) of respondents captured medically sensitive images with a smartphone, yet no consent was obtained in 24% of those cases. Among the physicians who did obtain consent, “only 7% gained written consent, while 78% failed to document the procedure in the patient record,” the researchers discovered.

Of those who snapped clinical photographs on their smartphones, 64% stored the images on their personal device and 82% shared them with someone else, “mostly for input from another physician,” the study authors wrote. However, the physicians’ methods for sharing medical images included non-secure delivery techniques like multimedia-messaging service (MMS), email, and instant messaging, and one respondent alarmingly admitted to uploading such images to a social networking website.

“There has been much debate regarding the ethics and legality of taking clinical photographs using personal cameras … (but) in practice, it appears that these considerations have little impact on clinicians, who most commonly use a personal digital camera,” the researchers concluded. “This study supports the notion that, although clinical photography is commonly used in clinical practice, there is a general lack of understanding regarding policy, image ownership, professional obligation, and risks associated with the use of smartphone technology.”

Although Kirk and his colleagues recognized “the ultimate aim of capturing, storing, and sharing clinical photographs should be to improve the outcome for the individual patient, (and) photography is a useful adjunctive means of accomplishing this goal,” they noted that “users of smartphone cameras for clinical purposes require education into their responsibility regarding patient privacy and photography.”

“The core policies and principles are no different to using a film camera or stand-alone digital camera and, in many organizations, almost certainly already exist,” the authors concluded. “The major difference in using a smartphone camera is the ease of making a clinical photograph publicly available, which presents more of an education issue than a policy issue.”