Publication

Article

Family Practice Recertification

Is This Teenager a Good Candidate for an IUD?

Author(s):

Although they are underutilized, intrauterine devices are among the safest and most efficacious forms of birth control available for adolescents.

You see a 16-year-old female for contraceptive counseling following her recent miscarriage at 10 weeks. She states that she had been taking a birth control pill at the time of her recent pregnancy, though she admits that she often forgot to take it. She has heard the intrauterine device (IUD) is “better,” but it is generally not recommended for teenagers.

How do IUDs compare to birth control pills on efficacy?

IUDs have clearly been proven more effective than combined oral contraceptives in preventing pregnancy. For the copper IUD, the one-year typical use failure rate is 0.8 per 100 women, and for the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS), it is 0.2 per 100 women.

Although the perfect-use failure rate for the pill is 0.3 per 100 women, the typical-use failure rate is as high as 9 per 100 women. In fact, one large trial suggested the IUD is more than 15 times more effective than the pill in preventing pregnancy.1

Are IUDs appropriate for adolescent females?

IUDs are among the safest and most efficacious forms of birth control available. Although they are underutilized in the United States due to bad publicity stemming from the era of the deadly Dalkon Shield, the rest of the world has continuously promoted the use of IUDs in adolescents and young adults.

Currently, the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG) strongly supports IUD use among adolescent females. In 2012, ACOG issued a committee opinion that stated “long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) — IUDs and the contraceptive implant — are safe and appropriate contraceptive methods for most women and adolescents.”2

“These contraceptives have the highest rates of satisfaction and continuation of all reversible contraceptives,” the statement continued. “Adolescents are at high risk of unintended pregnancy and may benefit from increased access to LARC methods.”

When I discuss IUDs with my adolescent patients, I inform them that the devices afford great efficacy rates in preventing pregnancy, but they still must use condoms to protect themselves from sexually transmitted infections (STIs).

Can IUDs be used in nulliparous women?

Although nulliparity was formerly viewed as a contraindication to IUD use, that is no longer the case. In fact, guidelines from both the ACOG3 and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) consider multiparous and nulliparous patients to be suitable IUD candidates.

While older studies have suggested higher rates of IUD expulsion and removals due to bleeding and pain in nulliparous women, more recent studies indicate no difference in risk with the LNG-IUS and only slightly increased risk with the modern copper IUD. However, a nulliparous woman may have a narrower cervical canal than a parous woman, which can make the procedure more challenging for the provider and more uncomfortable for the patient. In light of this, I often premedicate with a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) and use a paracervical block.

What IUD options are available?

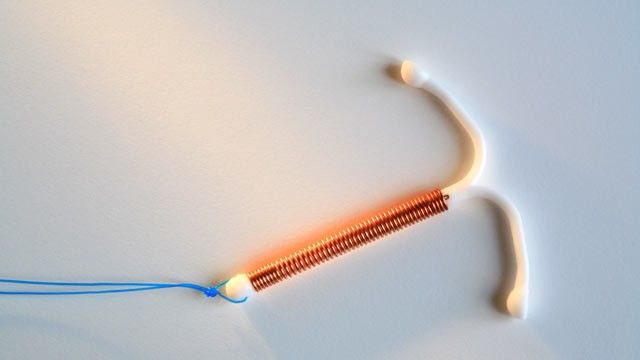

Currently, 3 types of IUDs are available in the United States: ParaGard, Mirena, and Skyla.

Because ParaGard is a copper IUD, it does not affect hormone levels thus avoiding potential symptoms and side effects associated with hormonal forms of birth control. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved ParaGard for 10-12 years of continuous use.

Mirena, an LNG-IUS, locally releases a small amount of a progestin-like hormone called levonorgestrel, which prevents egg release, makes the uterine lining unfavorable for implantation, limits the sperm’s ability to fertilize the egg, and thickens the cervical mucus to further hinder sperm motility. Mirena is FDA approved for 5-year continuous use.

Skyla, a “mini-Mirena,” is the newest IUD on the market, as the FDA approved it in February 2013. Since it releases fewer hormones, it is only effective for 3 years.

What advantages does Skyla offer?

Since Skyla is smaller than Mirena, it is easier to insert, especially in adolescent and nulliparous women. As with all IUDs, compliance with Skyla is not an issue, because once it is inserted, there is no need to remember to take the pill daily, change the patch weekly, or insert a new ring every 3 weeks.

Both Skyla and Mirena cause a reduction in the amount of bleeding. In fact, 12% of patients who receive these IUDs become amenorrheic. In certain individuals, such as those with menorrhagia or severe dysmenorrhea, use of hormonal IUDs can sometimes help prevent certain gynecologic surgeries.

Should an IUD only be inserted during menses?

While IUD placement during menses has been associated with an increased incidence of expulsion, there are a few advantages to note:

- Since the patient is already bleeding, it is known that she is not pregnant.

- The endocervical canal is a bit more dilated during menses, so it may be easier to insert the IUD.

- Insertional bleeding that can occur with the procedure is masked.

Although it is best to insert Mirena or Skyla within 7 days of the patient’s last menstrual period, ParaGard can be inserted at any time during the patient’s cycle, after determining that she is not pregnant. ParaGard can even be used as a form of emergency contraception, since it can be placed within 5 days of unprotected intercourse.

Do IUDs increase the risk of pelvic infections?

Clinical trials have demonstrated the risk of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) is greatest in the first month following IUD insertion, due to instrumentation. However, adhering to sterile techniques and changing the frequency of IUD replacement can help diminish the risk of PID. Afterwards, a patient’s odds of developing PID are no greater than her odds of acquiring an STI.

For the copper IUD, in particular, 2 separate studies have shown that same-day placement is safe and effective, and it has not been associated with higher rates of PID.

Do IUDs increase the risk of ectopic pregnancy?

Studies have shown that IUDs do not increase the risk of ectopic pregnancies. However, if a patient were to become pregnant with an IUD in place, the pregnancy is more likely to be ectopic from a hormonal IUD than a copper IUD.

Based on their package inserts, LNG-IUSs should not be used in women with a history of ectopic pregnancy. However, that is not the case for the copper IUD, as it is considered an acceptable form of birth control for those with a previous ectopic pregnancy.

Should screening for STIs be performed prior to IUD insertion?

Since women aged 15-19 years have increased risk for chlamydia and gonorrhea, the ACOG guidelines recommend screening all adolescents for STIs either at or before IUD insertion.2 If an STI is diagnosed after an IUD has been placed, then the ACOG recommends treating the infection without removing the device.

Additionally, a recent Kaiser study supported IUD insertion protocols “in which clinicians test women for Neisseria gonorrhea and Chlamydia trachomatis based on risk factors and perform the test on the day of insertion.”4

Is antibiotic prophylaxis indicated?

Studies have consistently shown prophylactic antibiotics at the time of insertion provide no clear benefit in low-risk women. Therefore, antibiotic prophylaxis is not recommended.

How much do IUDs cost?

IUDs are the least expensive long-term and reversible form of birth control. The medical examination, device, insertion, and office follow-up visits typically total between $500 and $1,000, though it is important to note that this aggregate cost is spread out over 3, 5, or 10 years, based on the type of IUD. Additionally, the Affordable Care Act classifies intrauterine contraception as a preventative service that is covered by insurance.

References

1. Winner B, et al. Effectiveness of long-acting reversible contraception. N Eng J Med. 2012 May 24;366(21):1998-2007. http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1110855.

2. Committee on Adolescent Health Care Long-Acting Reversible Contraception Working Group, The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion No. 539: Adolescents and long-acting reversible contraception: implants and intrauterine devices. Obstet Gynecol. 2012 Oct;120(4):983-8. http://www.acog.org/Resources-And-Publications/Committee-Opinions/Committee-on-Adolescent-Health-Care/Adolescents-and-Long-Acting-Reversible-Contraception.

3. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 121: Long-acting reversible contraception: implants and intrauterine devices. Obstet Gynecol. 2011 Jul;118(1):184-96. http://www.acog.org/~/media/Practice%20Bulletins/Committee%20on%20Practice%20Bulletins%20--%20Gynecology/Public/pb121.pdf?dmc=1&ts=20120908T1124504893.

4. Sufrin CB, et al. Neisseria gonorrhea and Chlamydia trachomatis screening at intrauterine device insertion and pelvic inflammatory disease. Obstet Gynecol. 2012 Dec;120(6):1314—21. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23168755.

About the Author

Michele Hoh, MD, is a board-certified family physician and Associate Clinical Professor of Medicine at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA. All questions were posed by Family Practice Recertification Editor-in-Chief Martin Quan, MD.