Publication

Article

ONCNG Oncology

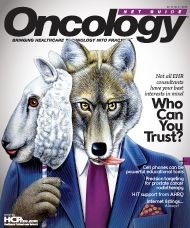

We're From the Government and We're Here to Help

Author(s):

Financial help for physicians who are willing to implement, test, and help optimize health IT systems.

The AHRQ Health IT Resource Center

Financial help for physicians who are willing to implement, test, and help optimize health IT systems.

If economics is the dismal science, Health economics is its most dismal branch. Hardly anything in medicine is priced rationally, inefficiencies abound, and cost-effective solutions are rare. Consider health IT, the sales pitch for which sounds irresistible: it promises to slash prescription costs, reduce errors, and streamline the entire healthcare system. Even better, recent studies have shown that some of those claims are actually true. How can doctors continue to reject such a compelling business argument? Easily. The costs of health IT systems fall almost entirely on physicians and hospitals, but most of the benefits flow to insurers, patients, and the public. Worse, health IT is still in its infancy, so early adopters must invest considerable time and money just to figure out which systems work best. Doctors simply can’t afford to do the right thing. An economist would diagnose this as a “positive consumption externality,” and prescribe a government subsidy to treat it.

In 2004, Congress earmarked money to do just that, through the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). “What they realized was there are a number of activities or research areas that sort of cut across the standard organizational structure of the agency, centers, and offices, and health IT is certainly one of those,” says Bob Mayes, senior advisor to AHRQ’s Center for Primary Care, Prevention and Clinical Partnerships.

Harder than it looks

As a research organization, AHRQ focuses on funding studies to test and optimize health IT systems, but it can also help clinics and hospitals make the initial purchase. Indeed, the first round of grants was aimed at getting the technology into small, rural hospitals. “There had been some successful examples of electronic medical records and other uses of health IT to improve safety and quality, but historically they had been really confined to larger institutions, big academic medical centers, or other large integrated delivery systems, such as the VA or Kaiser,” says Mayes. “The question really was ‘Why hasn’t it trickled down into smaller facilities?’”

Although money is certainly part of the problem, AHRQ’s research has revealed more insidious difficulties as well. For example, newcomers to e-prescribing often view it as a simple series of data transactions; the reality is far more complex. A physician must write the correct prescription, and a pharmacy with an entirely different system must fill it, raising numerous compatibility and implementation problems. After those hurdles, the e-prescription faces an even tougher challenge. “The most important piece of the whole thing is did the patient actually take the medication?” says Mayes, adding that “We’ll continue to look at e-prescribing, but we also are looking more at how we move into the whole area of adherence.”

To address such multifaceted problems, AHRQ funds a wide range of health IT grants, from $100,000 to $1.2 million, enabling everything from small-scale, proof-of-concept studies to large, demonstration projects. With a total annual budget around $45 million, the agency must turn down many applicants, but Mayes says they take pains to make the process straightforward.

“One of the things we’re trying to do is get involvement with a broader cross-section of the health sector,” says Mayes. “Ultimately, if we put out findings, we need to have people go on the website and look at the kinds of things that research has been done on and say ‘oh, yeah, that’s me, that’s my practice.’”

Those efforts seem to be paying off. “The AHRQ folks were very easy to work with,” says Rick Breuer, MD, an attending physician at Community Memorial Hospital in Cloquet, MN, and the lead investigator on a recent AHRQ health IT project. “Going after a Federal grant was kind of scary for us because we weren’t sure how much of a jumble of paperwork and regulations we might have to meander through, but it was really a very good process.”

The pharmacist is always in

The Minnesota team used its AHRQ grant to see whether small, rural hospitals would benefit from using a networked e-prescribing system. The project connected small facilities across the state with a 24-hour pharmacy at St. Luke’s hospital in Duluth. “That’s really what the purpose of this whole project was: to give everybody access to that 24-hour pharmacy coverage,” says Breuer.

Once the system was set up, physicians at any of the hospitals in the network could send their prescriptions to the pharmacy in Duluth for immediate review. Having a dedicated pharmacist on call was a boon for physicians accustomed to more limited coverage, and the hospitals kept the system running after the grant expired. “Every facility has stuck with it. It is an expense that we have now that we didn’t have before, but I think we see it being worth it in the satisfaction of our staff and our own pharmacists when they come back on a Monday morning and how everyone feels about what this means for patient care,” says Breuer.

E-prescribing can also provide more quantifiable benefits, as another AHRQ project recently demonstrated. Researchers analyzed data from physicians using the PocketScript system and discovered a substantial payoff : a single feature of the program saved $845,000 per 100,000 patients per year. “The device or the program actually looked up the patient and got that patient’s formulary from their own insurance company and then informed the physician of the tiers of the co-payments, so the physician knew at the point of prescribing what the tier was,” says Joel Weissman, PhD, senior health policy advisor, Massachusetts Executive Office of Health and Human Services, and study co-author.

The feature was unobtrusive, simply listing medications in different font colors based on their formulary tiers, but it influenced prescribing practices. “Doctors want to do the right thing. If there’s a choice of drugs and if they can help out the patient to pay a lower co-payment by prescribing an equivalent drug in a lower tier, they’re going to do that,” says Weissman.

The apparent simplicity of such changes—pharmacy coverage and colored fonts are hardly technological breakthroughs—highlights what many see as the real challenge of health IT. “It wasn’t technically overly challenging to put networked pharmacies together—it was more getting all of these people together and changing our process,” says Breuer.

Schedule the colonoscopy, HAL

Although e-prescribing is certainly hot, AHRQ funded researchers are looking at many other aspects of health IT as well. Indeed, individual sites often host multiple projects in distinct fields, such as the three-pronged effort now underway at the University of Texas Medical School in Houston, TX. There, assistant professor of medicine Eric Thomas, MD, is testing new technologies in settings ranging from intensive care units to outpatient clinics.

In the ICU, Thomas and his colleagues are studying the impact of remote presence systems. “There’s a severe shortage of intensivists in the United States, and so the idea is that by putting a few intensivists in an off -site location and then connecting them via telemedicine technology to numerous ICUs, you could kind of help provide more coverage and more care by intensivists to more patients,” says Thomas. The study is using the VISICU telemedicine system, but its results, which Thomas expects to have soon, should be relevant to competing products as well.

Another study focuses on developing algorithms to detect diagnostic errors by analyzing electronic health records. “What we’re doing is looking at things like visit patterns to try and detect a diagnostic error. For example, if a patient sees their primary care physician today, and then three days from now they go to the emergency room or get admitted to the hospital, it may be an indicator that the primary care physician missed something, and then a few days later it got worse and they ended up in the hospital,” says Thomas. Of course, there could be other explanations for such a pattern, so the algorithm also incorporates additional clinical information. Ultimately, the system might function like audit flags in tax-processing software, automatically highlighting areas for a human to check more closely.

Even so, any error-checking system could be a tough sell if it’s not implemented carefully. “There might be some resistance when it gets rolled out as a day-to-day quality tool,” says Thomas, adding that a key issue will be “whether or not it’s in a punitive environment or an environment that’s focused on learning and improvement; it depends just on the culture of the place.”

Thomas’s colleagues are also working on a less controversial application of the technology, analyzing health records to keep cancer patients from getting lost in the healthcare system. “Let’s say a 60-year-old man presents with a new iron deficiency anemia. If a man has a new anemia, then he needs to get a colonoscopy. We can detect the anemia, we can then screen to see if the colonoscopy occurred, if it did what was the pathology, if it was cancer, has that person seen a surgeon or an oncologist, if they have, have they also begun a therapeutic regimen?” says Thomas.

The price of freedom

When government-funded researchers produce new algorithms and software, they often release those products under open-source licenses so other researchers can copy and modify them. In health IT, things are more complicated. “There are really two pieces when you look at an application; there is the computer programming expertise and knowledge, and then there’s the domain expertise of what does it do and is it actually doing what it is supposed to?” says Mayes. He adds that it’s no accident that the open-source movement’s biggest successes have been operating systems such as Linux and general-purpose desktop applications. “If you look at Linux for instance, the very people that created the code were also the experts in operating systems,” says Mayes.

Making an open-source health IT application work requires a more rare form of dual expertise: medicine and computer programming. The scarcity of physician-programmers means that any health IT application requires a diverse team, and commercial software development may be the most practical way to achieve that.

The price difference—open source software is free, whereas commercial applications cost money—may not matter in health IT. “We’ve actually run focus groups with physicians and you often hear ‘what would you pay for an e-prescribing system?’ and a lot of them say ‘Well, free is not good enough,’” says Weissman. He adds that “It really does cost them time and hassle.”

That makes the economic prognosis sound dismal, but help is on the way: true to its mission, AHRQ is now gearing up to fund a new round of studies on health IT implementation.

Can AHRQ really make a difference in HIT implementation?

Alan Dove is a freelance healthcare and science writer.