Publication

Article

Cardiology Review® Online

Quality of Care and Outcome in Critical Access Rural Hospitals

Ragavendra R. Baliga, MD, MBA, FACP, FRCP (Edin), FACC

REVIEW

Joynt KE, Harris Y, Orav EJ, Jha AK. Quality of care and patient outcomes in critical access rural hospitals. JAMA. 2011;306(1):45-52.

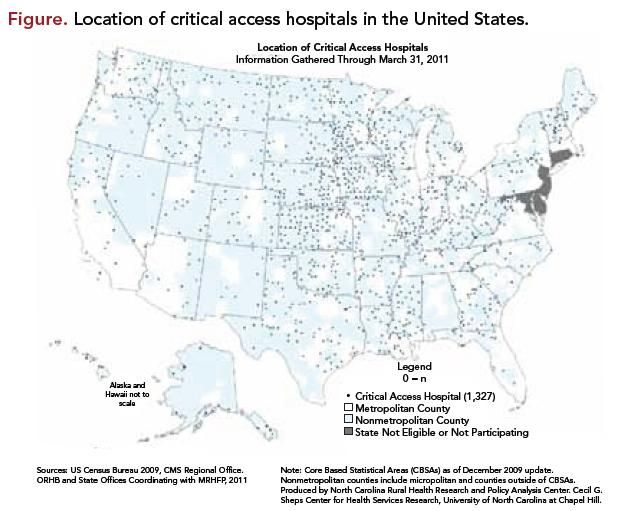

The Medicare Rural Hospital Flexibility Program (MRHFP) legislation of 1997 allowed the establishment of critical access hospitals (CAHs) to provide better access to the rural population.1 CAHs currently comprise about 25% of all acute care hospitals in the United States2 (Figure). These are defined as hospitals that are rural with no more than 25 beds, have a 4-day limit on length of stay, and are located more than 35 miles from the nearest hospital.1 These hospitals are reimbursed on a cost basis, unlike Diagnosis Related Group payments for larger hospitals.1 CAHs are required to maintain agreements with network hospital(s) for referral and transfer, and for credentialing and quality assurance.3 However, very little is known about the quality of care they provide and patient outcomes.

Study Details

To determine the quality of care and patient outcomes and to better comprehend disparities of care for CAHs versus non-CAHs, the authors conducted a retrospective analysis in 4,738 US hospitals of Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries who were discharged in 2008- 2009 with the following diagnoses:

1. acute myocardial infarction (AMI) (10,703 for CAHs vs 469,695 for non-CAHs),

2. congestive heart failure (CHF) (52,927 for CAHs vs 958,790 for non-CAHs), and

3. pneumonia (86,359 for CAHs vs 773,227 for non-CAHs)

The final study cohort consisted of 2,351,701 admissions across these three conditions. The main outcome measures assessed included:

1. clinical capabilities (the authors used the American Hospital Association [AHA] survey to quantify resources that have been associated with better care, including the presence of an intensive care unit [ICU], the ability to perform cardiac catheterization or surgery, and nurse staffing levels).

2. performance on processes of care (the authors used Hospital Quality Alliance [HQA] nationally reported data to obtain hospitals’ performance on process measures for AMI, CHF, and pneumonia during 2009), and

3. 30-day mortality rates (Medicare data were used to calculate mortality within 30 days of admission and then was adjusted for age, gender, race, and medical comorbidities).

Compared with other hospitals (n = 3,470), 1,268 CAHs (26.8%) were less likely to have:

• ICUs (380 [30.0%] vs 2,581 [74.4%], P <0.001)

• cardiac catheterization capabilities (6 [0.5%] vs 1,654 [47.7%], P <0.001), and

• basic electronic health records (80 [6.5%] vs 445 [13.9%], P <0.001).

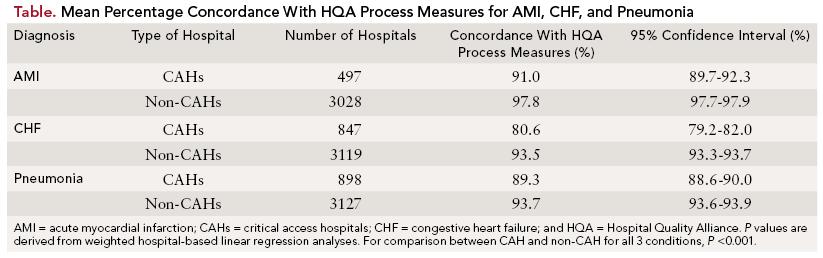

The CAHs had lower performance on processes of care than non-CAHs for all three conditions examined (concordance with HQA process measures) (P <0.001 for all three conditions) (Table):

1. AMI: 91.0% (95% confidence interval [CI], 89.7%-92.3%) vs 97.8% (95% CI, 97.7%-97.9%)

2. CHF: 80.6% (95% CI, 79.2%- 82.0%) vs 93.5% (95% CI, 93.3%- 93.7%), and

3. pneumonia: 89.3% (95% CI, 88.6%-90.0%) vs 93.7% (95% CI, 93.6%-93.9%).

Patients admitted to CAHs had higher 30-day mortality rates for each condition than those admitted to non-CAHs. Thirty-day mortality rates were reported as follows (P <0.001 for all three conditions):

1. AMI: 23.5% vs 16.2%; adjusted odds ratio [OR], 1.70; 95% CI, 1.61-1.80)

2. CHF: 13.4% vs 10.9%; adjusted OR, 1.28; 95% CI, 1.23-1.32; and 3. pneumonia: 14.1% vs 12.1%; adjusted OR, 1.20; 95% CI, 1.16- 1.24.

The study’s authors concluded that when compared with non-CAHs, CAHs had fewer clinical capabilities, worse measured processes of care, and higher mortality rates for patients with AMI, CHF, or pneumonia.

References

1. Balanced Budget Act of 1997, HR 2015, 105th Congress (1997).

2. Joynt KE, Harris Y, Orav EJ, Jha AK. Quality of care and patient outcomes in critical access rural hospitals. JAMA 2011; 306(1):45-52.

3. Bushy A, Bushy A. Critical access hospitals: rural nursing issues. J Nurs Adm. 2001; 31(6):301-310.

4. Pathman DE, Ricketts TC III, Konrad TR. How adults’ access to outpatient physician services relates to the local supply of primary care physicians in the rural southeast. Health Serv Res. 2006;41:79-102.

5. National Advisory Committee on Rural Health and Human Services. The 2010 Report to the Secretary: Rural Health and Human Services Issues. Available at www.hrsa.gov/advisorycommittees/rural/ 2010secretaryreport.pdf. Accessed September 30, 2010.

COMMENTARY

Opportunities to Improve Care

T

his study is important because CAHs provide health care to nearly 1 in 4 individuals living in the United States,2 and therefore reflects the standard of care to a substantial segment of the population. Typically, these hospitals serve rural residents who are older, tend to have lower incomes, are more likely to be uninsured, and have several comorbid conditions including hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and cancer.4 With the increasing age and longevity of the Baby Boomers, these hospitals will play an increasingly important role in care of the population—particularly in rural states.5

This study provides important information regarding not only the quality of care in rural hospitals but also opportunities to improve overall quality. The study found the key limitations of CAHs to be scarce resources (including competent personnel, a paucity of electronic health records, and widespread absence of performance measures). The results should provide an impetus to hospital administrators and health care providers in rural hospitals to utilize the scarce resources available to “do the right thing” for each and every patient. The study identifies the opportunity to improve the standard of care by adhering to consensus guidelines for management of acute coronary syndromes, CHF, and pneumonia by improving the process systems in each hospital, training health care providers staffing these centers, implementing electronic health records, partnering with neighboring centers, and utilizing telemedicine.

The study is important but has limitations. These include the utilization of administrative data that do not have important clinical and patient characteristics (such as level of educational status) that could affect outcomes and a lack of data on the experience or qualifications of the physicians providing care for patients at CAHs. Additionally, the impact of patient preferences in care were not evaluated— patients may have refused transfer for more advanced care due to personal preference even if clinicians recommended that a transfer occur. The study did not examine the role of outpatient care and thus was not able to assess to what extent these differences might affect the findings of the study, and the use of mortality to evaluate excellence of care is a crude measure of hospital quality.

The first step in improving quality would be to recognize errors (including errors of underuse, overuse, and misuse) of medical intervention for patients with AMI, CHF, and pneumonia. Each of the rural hospitals will benefit from developing a “culture of quality” in their respective institutions that includes taking inventory of their processes and striving to develop performance measures for each of these conditions. The ACC’s Guidelines Applied in Practice (GAP) initiative utilizes continuous quality improvement (CQI) tools to help health care providers and hospitals improve compliance with ACC/AHA guidelines.

Development of performance measures would require measurement of both processes (for example, administration of ACE inhibitors in heart failure) and patient outcome. Successful implementation of quality initiatives requires an organizational culture dedicated to improve the quality of care, including the “buy-in” of senior management and health care providers, innovative but flexible protocols, collaboration between health care providers and quality teams, a robust feedback process that is able not only to monitor but also rapidly implement changes, and an understanding of the dynamic nature of the quality of cardiovascular care.

Data collection methodologies available for CAHs include retrospective chart review, prospective data collection, collection of patient outcome data, and collection of patient experience data, including patient satisfaction. Retrospective chart review can be expensive and often complicated by the presence of multiple charts, and by legibility, accuracy, and completeness of charts. Prospective data collection is increasingly being used and hospitals have been partnering with the ACC’s National Cardiovascular Data Registry; this allows comparisons with similar institutions and with national benchmarks. Collection of patient outcome data by hospitals, such as mortality data, can be logistically challenging and even expensive. Therefore, most hospitals tend to measures processes such as utilization of aspirin, statins, etc, in AMI. Patient satisfaction scores can be complicated by the presence of comorbid conditions such as depression and have been found to correlate poorly with other measures of quality such as survival. Therefore, performance measures have focused on collection of quality measures that focus on processes such as “core measures” for heart failure, AMI, and pneumonia. CAHs could start their quality efforts by focusing on these “core measure” performance measures.

Implementation of performance measures includes improving operational effectiveness that will require replacement or renovation of aged facilities, acquisition of modern equipment and new technologies, investment for training personnel, and establishment of electronic records. Even if these hospitals can afford to do this, the cost of maintaining and upgrading these technologies can be substantial. Clearly, payors including the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services will have to evaluate levels of reimbursements and incentives for CAHs so that they can implement quality measures in a cost-effective fashion. It is important that the one-quarter of the US population receive critical “core-measures” medications known to reduce morbidity and mortality.

In conclusion, this study is important because it demonstrates key deficiencies in the US health care system and provides insights into opportunities to remedy these imperfections.

About the Author

Ragavendra R. Baliga, MD, MBA, FACP, FRCP (Edin), FACC, is Vice-Chief and Assistant Division Director, Division of Cardiovascular Medicine and Professor of Internal Medicine at The Ohio State University in Columbus. He received his MD from St John’s Medical College in Bangalore, India, and completed his residency at Victoria Hospital in Bangalore. He was a faculty cardiologist at the University of Michigan and received an MBA from the Stephen Ross School of Business. He co-founded a company that manages health care revenue cycles for physicians. Dr Baliga joined The Ohio State University in 2009.