Publication

Article

MD Magazine®

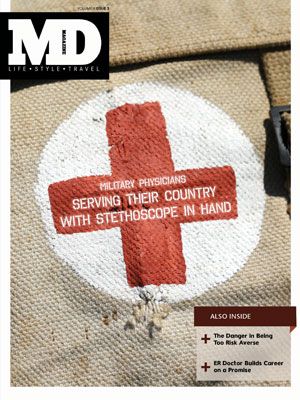

Serving Their Country With Stethoscope in Hand

Author(s):

Although they came from different backgrounds, these physicians all took their medical degree to the US Armed Forces to care for soldiers and serve their country.

When Raquel Bono attended medical school on a Health Profession Scholarship, she understood she would “pay back” the scholarship with a stint in the military. She admits, in retrospect, she anticipated putting in her time, then leaving the Navy to pursue a civilian career. It just didn’t happen that way.

“It was my first tour of duty that really convinced me that a career in military medicine was a very viable way of pursuing both a professional and a service objective,” she says.

Today, her title is Rear Adm. Bono, Medical Corps, with the US Navy. She credits what she has accomplished to that initial tour of duty in the first Gulf War.

“I saw that what I was actually participating in was something that was much larger than myself,” Bono says. “It also gave me an opportunity to give back. And that’s when it really hit me that being a part of the military was so much more than just pursuing my professional passion as a physician and a surgeon—but also understanding that I could help advance a much larger mission.”

From culture shock to reality

Bono says that, just as with most residents going through a training program, whether in a civilian or military setting, she did not know what to expect when first deployed. She found herself living in a tent, setting up a field hospital, and preparing to deal with casualties.

“There was this kind of ‘Oh my God, what have I gotten myself into’ experience,” she recalls. “That was a defining moment for me, personally and professionally.”

Returning from the Gulf War, Bono continued to perform her military duties in a naval hospital, where she taught other residents while providing medical care to military beneficiaries. She realized the work she was doing was not only rewarding, it was fun.

Finding herself at a crossroads, she opted to stay in the military “for another 4 or 5 years and see what happens.” What happened was the realization that perhaps she was in the right place.

“I saw that managed care was becoming a part of the healthcare picture,” Bono recalls. “And I realized that our military system was very much like the managed care system. We had a captive infrastructure, a captive patient population, providers, and we defined the benefit. I felt that my background in the military would prepare me for all the changes I saw happening in managed care.”

In addition, doors to new opportunities continued to open. Bono began taking on leadership and decision-making roles in ways her colleagues on the civilian level were not. She realized she had an opportunity to bring positive change to healthcare—not just in the military, but also on a national stage.

By the time she looked up and caught her breath, she had built a career in military medicine.

“I chose the medical profession because a part of my value system is being able to help take care of others who are in need; and being able to offer them health and well-being, or relief from suffering,” Bono says. “And for me, as a physician, being able to do that on a much wider basis to not only the men and women of the military, but then also to the overall effort of our country, that’s a very rewarding aspect for me.”

Part of the bigger picture

Capt. Glen Crawford, Medical Corps, US Navy, graduated from McGill University in Montreal, Quebec, with a BA in Canadian and French-Canadian Studies in 1988. He’s come a long way since then.

He was in Washington, DC, during the attacks on 9/11, assisting families that had been affected, and led a team of 60 Army and Navy reservists and civilian personnel in tracking all wounded US and Coalition forces transitioning through Landstuhl Regional Medical Center in Germany following Operations Iraqi Freedom and Enduring Freedom.

“Those opportunities make wearing a uniform and serving our sailors, soldiers, and airmen a very rewarding and fulfilling experience,” Crawford says.

Today, in addition to his military rank, Crawford is an assistant professor of psychiatry at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences. He talks about the difference between helping members of the military recover not just from physical injuries, but emotional ones, as well.

“The [emotional] wound is not obvious to the human eye, at least not in the same way that a laceration, or a broken limb, or some other injury like that would be,” Crawford explains. “They’re often described as the invisible wounds of war. But military mental health has been very successful in returning service members to duty. Returning people to a level of functioning they had previously, not only as members of the military, but also with their families, with their coworkers, again, is very rewarding.”

Crawford has relocated frequently during his military tenure, living in Italy, Japan, Germany, and Guam. He says everyone has his or her own idea of adventurism, and he was excited to experience different cultures. In Italy, he lived in downtown Naples in an apartment owned by a local family that adopted him during his stay.

“I got to live like a Neapolitan,” he says. “I got to interact with people and learn a bit of the language. It made for a richer experience.”

And while he has experienced a wide range of emotions during his medical and military careers, he has taken the positives out of every experience.

“It’s certainly compelling when someone has been severely injured as a result of their service,” Crawford explains. “Not everyone who came through Landstuhl was injured to a severe extent. But the ability to be part of getting them where they need to go, getting them home, was emotional in a very positive and very rewarding sense.”

Life imitating art

The military bug bit Lt. Cmdr. Eric Deussing, MC (FS), US Navy, a supervisory public health emergency officer, when he was still an adolescent.

Forbidden by his parents from watching the Tom Cruise film Top Gun, because he was too young, he watched it on the sly at a friend’s house. From that point on he was convinced that he wanted to be in the Navy.

Armed with that determination, Deussing, at the age of 12, mailed a business reply card that he tore from a magazine to Naval Recruiting stating he wanted to join. The letter he received from a Navy captain in return, accompanied by a poster, encouraged him to “look into the Naval Academy or ROTC when he got to high school.”

Deussing began examining different scholarship programs, and eventually took a Navy ROTC scholarship to Tulane University. He was determined to become a naval flight officer, and added medicine to the equation while doing his undergraduate work. His dream came true when he graduated from the Naval Aerospace Medical Institute’s flight surgery program in Pensacola, FL.

“Navy flight surgery is probably one of the best jobs in the world,” Deussing says. “The navy flight program is really unique in that you actually get to do the same course work that the pilots and naval flight officers go through.”

While he spent 2 months in a classroom learning aerospace medicine—primary care relating to G-forces, altitude, and decreased oxygen—the rest of the time was spent with flight students learning aerodynamics, navigation, engine systems, and going out and flying the airplane.

“It’s really an amazing experience,” he says. “And you might think it sounds like an adventure vacation experience, but it’s really to prepare doctors who are then going to go out and take care of these squadrons. We understand the physical challenges that come with flight, because we’ve flown the airplane.”

Deussing says the most rewarding aspect of his career is the relationships he formed within the naval flight community. It’s a unique role, he says, to be the physician, but also a peer to members of the squadron.

“It’s one of those unique opportunities that you just can’t do at Duke or (Johns) Hopkins if you were a staff doctor there,” Deussing says. “You can do a lot of great things, but you’re not going to be a navy flight surgeon.”

The preacher’s daughter

By her own admission, Capt. Mae Pouget was a preacher’s kid and a Navy brat, but had no intention of signing up. Her father, Thomas Parham, became the second black chaplain in the US Navy in 1944, and, 22 years later, the first black officer to attain the rank of captain. But Pouget actually turned down a scholarship from the Air Force early on.

Medicine was a different story.

“When I was about 10 years old, I realized I was a very good listener,” Pouget explains. “I didn’t know my grandfather, who was a general surgeon, but when I visited my grandmother’s house I would read his surgical books because I found them interesting. And so, by third grade, with my listening skills and fascination with medicine in general, I thought that might not be a bad career choice.”

But during her residency she realized that “the civil hospital lifestyle wasn’t really appealing to me.” She contacted a local recruiter, said she was interested in joining the Navy, and signed on. She has not regretted the decision.

“I talk to my peers in the civilian sector, and the variety that we have in the military system is just fantastic,” Pouget says. “Not that medicine isn’t interesting anyway, but I just didn’t see myself going 9 to 5 to a job for 30 years at the same place. Because I’m a navy brat, I never lived anywhere longer than 5 years. And when I get too close to 5 years, I start getting really uncomfortable—rearranging furniture, feeling like I need to do something. Adding in my interest in medicine made it a perfect fit for me.”

Today, Pouget’s rank is captain, Medical Corps, and she’s the Navy Medicine Chief Diversity Officer, as well as the Special Advisor on Diversity to the Surgeon General. Diversity, she explains, is critical to success from both a military and medical standpoint.

“As an organization, we’re competing with civilian organizations for the best and the brightest,” Pouget says. “And we need to be able to relate to diverse people to recruit into our organization. Our patients are diverse, from all over the world, all different kinds of backgrounds; we need to be able to understand their culture in order to provide the care for them.”

And while Pouget says her father would have been proud of her even if she’d become a bag lady, she acknowledges he was excited when she joined the Navy.

“There’s a plaque at home that has 3 shoulder boards: my brother’s (Naval Academy class of 1985), my dad’s, and mine,” she says. “And the plaque says, ‘The tradition continues from father to son and daughter.’”

The start of a career

Alex Blau, ENS, MS, US Naval Reserve, is currently attending The Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine, and will go on active duty once he graduates. Medicine became his first interest when he began shadowing physicians at a hospital during his senior year in college.

When he spoke with several physicians who were former military doctors and learned of their experiences, he knew he’d found the entry point to his career.

Blau is taking advantage of the Health Professional Scholarship program. For every year of medical school the military pays for, he owes them one year of active duty service as a physician. His tuition, textbooks, materials like scrubs or stethoscopes, and even a stipend to live off are all covered by the military.

“The Navy’s goal is to make your experience in medical school less stressful, so you can just focus on doing what you need to do—which is getting through medical school,” Blau explains. “And the service component (while in medical school) is 45 days of active training every year. It’s not exactly boot camp, but it’s the equivalent. In the Navy we call it officer development school.”

Having just completed his first year of medical school, Blau says it’s way too early to forecast whether he’ll stay in the military at the end of his commitment, or move on to a civilian career. Either way, he points out, he’s going to be practicing medicine.

“That’s what I really want to do,” he says. “And the Navy thing has been such a great opportunity, I’m very excited and glad I made this choice.”