Publication

Article

Family Practice Recertification

Why Does This Male Patient with Rheumatic Heart Disease Have Congestive Heart Failure?

Author(s):

The patient is a 48-year-old male with "heart trouble" since the age of 6 years, after having rheumatic fever. He was treated with digitalis and diuretics until he was 31 years of age when he was admitted for heart failure and underwent closed commissurotomy.

James D. Collins, MD

History:

The patient is a 48-year-old male with “heart trouble” since the age of 6 years, after having rheumatic fever (1). He was treated with digitalis and diuretics until he was 31 years of age when he was admitted for heart failure and underwent closed commissurotomy (mitral valve replacement).

RADIOGRAPHIC FINDINGS:

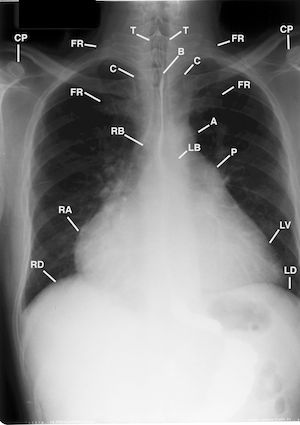

Figure 1 is of the posterior-anterior radiographic view of the heart that displays the enlarged rounded left ventricle depressing the left diaphragm due to hypertrophy and distension of the left ventricle due to dilatation. The image also displays the splayed apart bronchi accentuating the elevation of the enlarged left atrium; extension of the right cardiac margin farther to the right than normal, with increased convexity of the right ventricle enlargement, prominent left atrial appendage/enlarged pulmonary trunk; elevated right hemidiaphragm from the enlarged liver, bilateral single Kerley B line(s) at the base of the lungs, and cephalization of the upper lung veins (2).

Figure 1 is the posterior anterior chest radiograph of the 4 views of the chest with barium (B) in the esophagus. This image displays the anterior rotated clavicles over the asymmetric posterior third ribs with drooping of the forward right shoulder; markedly enlarged left ventricle (LV); enlarged left atrium that splays apart the right main stem (RB), and left main stem bronchi (LB); large right atrium (RA); pulmonary trunk (P), and small ascending aorta (A). Clavicle (C) and Coracoid processes (CP); First ribs (FR); Left and right hemidiaphrgam (LD, (RD); Trachea (T), and cephalization of the pulmonary veins (not labeled) suggestive of congestive congestive heart failure.

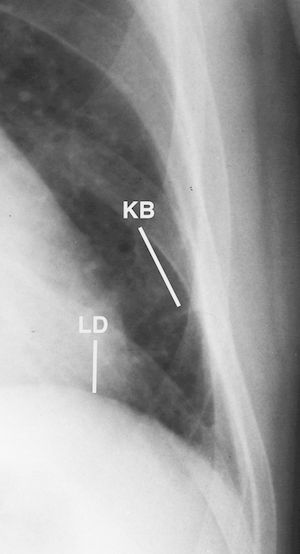

Figure 2 was obtained as an enlargement of the left lung base of Figure 1 to display a single “Kerley B line” of chronic lymph stasis of congested cardiac failure.

Figure 2 is a cone down image of Figure 1 that displays a single “Kerley B line” (lymphatic) (KB) adjacent to the pleura of the left lung reflecting lymph stasis. Left hemidiaphgram (LD)

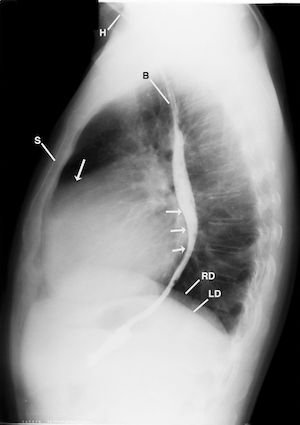

Figure 3 was obtained in the left lateral projection of the heart to display the right ventricle enlargement encroaching on the retrosternal clear space and the enlarged left atrium displacing the esophagus posteriorly.

Figure 3 is the left lateral chest radiograph of the 4 views of the chest with barium (B) in the esophagus. Observe the mild kyphosis of the thoracic spine (not labeled); enlarged left atrium (3 arrows) backwardly displacing barium in the esophagus; a single arrow reflecting the region of the enlarged right ventricle and pulmonary trunk (not labeled). Humerus (H), left and right hemi- diaphragm (LD, RD), Sternum (S).

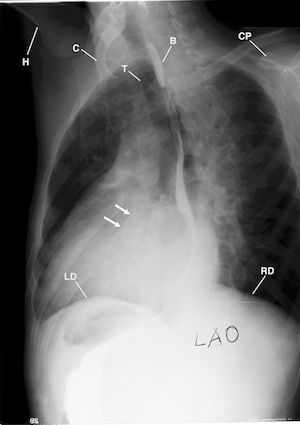

Figure 4 is the left anterior oblique (LAO) radiograph of the heart squaring off the right atrial appendage with compression of the entire right cardiac margin with the enlarged left ventricular arc.

Figure 4 is left anterior oblique (LAO) chest radiograph that displays the backward barium (B) in the esophagus displacing the esophagus, accentuating the enlarged left ventricle (not labeled) over the region of the thoracic vertebra. Clavicle (C), Coracoid process (CP). Humerus (H), Left and Right hemidiaphragm (LD, RD), Trachea (T), and calcification in the region of the aortic valve (2 arrows).

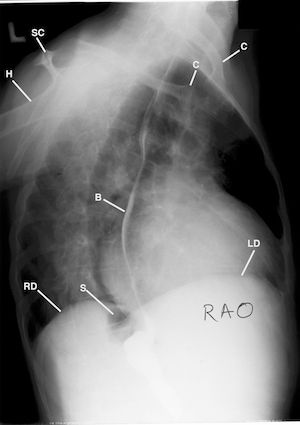

Figure 5 is the right anterior oblique (RAO) radiographic that displays the increased prominence of the pulmonary artery increased convexity of the right ventricle.

Figure 5 is the right anterior oblique (RAO) chest radiograph that displays the backward barium (B) in the displaced esophagus, accentuating the enlarged left ventricle (not labeled) displaced over the region of the thoracic vertebra. Clavicles (C), Humerus (H), Left and Right hemidiaphragm (LD, RD), Stomach (S), Scapula (SC), Trachea (T).

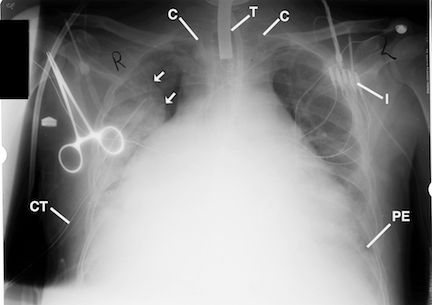

Figure 6 is the anterior posterior radiographic of the chest radiograph post mitral commisurotomy that displays the markedly enlarged heart post surgery for left atrial bleeding; left heart border and the left diaphragm marginated by mediastinal blood or loculated pleural effusion; bilateral pleural effusions; right chest tube introduced into an area of hemorrhage for withdrawing fresh blood; bilateral pleural effusions and bilateral parenchymal densities of pulmonary edema, aspiration pneumonia or pulmonary hemorrhage, lucent line between the right pericardium and the region of hemorrhage in the right lung reflecting pulsations of the heart against the edematous right lung, and the faint display of the distented upper lung veins (cephalization);.

Figure 6 is the anterior posterior chest radiograph post mitral commisurotmy that displays the markedly enlarged failing heart post surgery for left atrial bleeding prior to the patient's demise.

The presence of Kerley B lines are thickened, edematous interlobar septa (lymphatics). They are suggestive for the diagnosis of congestive heart failure. They may be displayed in pulmonary edema, sarcoidosis, lymphangitis, carcinomatosis, interstitial pulmonary fibrosis, lymphoma, and pneumoconiosis. They can be a fleeting sign of congestive heart failure. (3)

Observe the left heart border and the left hemidiaphragm marginated by mediastinal blood or loculated pleural effusion; bilateral pleural effusions (PE); right chest tube (CT) introduced into an area of hemorrhage (2 arrows) for withdrawing fresh blood; bilateral pleural effusions and bilateral parenchymal densities (not labeled) of pulmonary edema, aspiration pneumonia or pulmonary hemorrhage, and the lucent line between the right pericardium and the region of hemorrhage (2 arrows) in the right lung reflecting pulsations of the heart against the edematous right lung. Heads of the anterior rotated clavicles (C), Wire leads for intracardiac pacemaker monitoring (I). Indwelling tracheostomy tube in the trachea (T), and a metal Clamp (not labeled) over the right anterior shoulder.

DISCUSSION:

The heart’s function is to maintain an output of blood sufficient to supply the oxygen needs of the body tissues. Congestive heart failure occurs when the heart muscle does not pump blood as well as it should. The heart decompensates, and dilates, and loses its well-rounded contour on Posterior-Anterior (PA) chest radiographs as in our patient. The projected heart size increases in width, both to the left and to the right. Important indications of the physiologic state of the failing heart is found by studying the margins of the heart and lung fields on chest radiographs. In acute left ventricular failure which develops very rapidly, fluffly increased densities about both hila may indicate pulmonary edema. In more gradually developing heart failure the hilar vessels appear enlarged and tortuous and are displayed to extend farther out into the lung fields (cephalization) than they do normally at that caliber.

With long standing failure, very striking changes appear in the lung fields. The lungs may appear hazy and less radiolucent than normal. Short, parallel horizontal lines of increased density at the lung bases close to the costophrenic angle , which have been identified as distended lymphatics (Kerley B lines) of the interlobular septa, become visible as interstitial edema increases. A subpleural accumulation of fliud displayed tangentially just inside the rib cage (pleura) close to the costophrenic angle should be looked for and will generally precede the appearance of a pleural effusion.

TAKE HOME MESSAGE

The knowledge of a patient’s history, landmark anatomy and the pathophysiology that accompany a particular disease is important in making an accurate diagnosis from plain radiographs. In our patient, developed congestive heart failure because of complications of his mitral valve replacement.

Since the esophagus is in the posterior mediastinum close to the descending aorta and cardiac structures, radiographic studies of the heart on plain chest radiographs is made possible by the use of a barium swallow as part of the radiographic study of the heart prior to cardiac catherization.

References:

1. TEXT BOOK OF Pathology with clinical applications, STANLEY L. ROBBINS M.D. W.B. SAUNDERS COMPANY, PHILADELPHIA & LONDON; 1957; pp 435- 453

2. Meschan I. Analysis of Roentgen Signs in General Radi ology. Philadelphia, Pa: WB Saunders Co; 1976:332-385.

3. Collins JD, Shaver M, Disher A, Batra P, Brown K, M iller TQ. Imaging the Thoracic Lymphatics: Experimental Studies of Swine. Clin Anat. 1991