Publication

Article

Cardiology Review® Online

Effect of Rate Control on QOL in Patient With Permanent AF

Author(s):

Noel G. Boyle, MD, PhD

REVIEW

Groenveld HF, Crijns HJGM, Van den Berg MP, et al. The effect of rate control on quality of life in patients with permanent atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:1795-1803.

D

espite a decade of important clinical trial data on the management of atrial fibrillation (AF), no other arrhythmia continues to present so many clinical challenges. While the Atrial Fibrillation Follow-up Investigation of Rhythm Management (AFFIRM) and the Rhythm Control versus Rate Control for Atrial Fibrillation and Heart Failure (AF-CHF) “rate control versus rhythm control” trials showed that the rate control approach was not an inferior strategy, 1,2 these studies left many unanswered questions for both approaches.

Rate control appears simple and possibly easier to achieve than rhythm control; however, the exact definition of what constitutes optimal “rate control” has been contentious. This question was taken up by the RACE II (Rate Control Efficacy in Permanent Atrial Fibrillation: a Comparison between Lenient versus Strict Rate Control II) trial investigators, who evaluated a historically defined “strict” rate control versus a more “lenient” rate control in patients with permanent AF.3

Strict rate control required a target heart rate <80 beats/minute at rest, and <110 beats/minute during moderate exercise, while lenient rate control allowed the target resting heart rate <110 beats/ minute. In a randomized study of 614 patients with permanent AF, with a minimum of 2 years of follow-up, the composite primary outcome, defined in the trial as death from cardiovascular causes, hospitalization for heart failure, stroke, systemic embolism or bleeding, and lifethreatening arrhythmic events, showed that the lenient rate control approach was non-inferior.

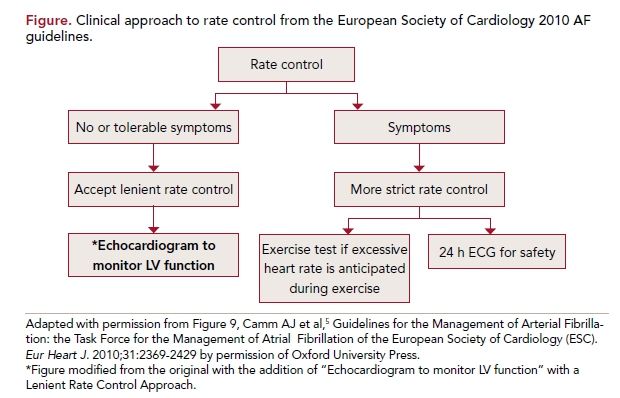

Indeed, the primary outcome was lower in the lenient rate control group (12.9%) than in the strict rate control group (14.9%). The frequency of symptoms and adverse events was similar in both groups. These findings have been incorporated in the most recent American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology4 and European Society of Cardiology5 guideline updates on AF (Figure).

The Dutch group that carried out the RACE II study has recently also reported on the effect of the different rate control approaches on remodeling6 and quality of life (QOL)7 in patients with permanent AF. Perhaps surprisingly, there were no differences in changes in left atrial size or left ventricular end-diastolic diameter between the 2 groups. This finding will address a concern raised by many that lenient rate control would more likely result in tachycardia-mediated cardiomyopathy. Recently, these investigators have published a detailed analysis of the effect of the different approaches to rate control on QOL in patients with AF, which is the focus of this report.

Study Details

In this analysis of the RACE II trial data, the authors studied a total of 437 patients with permanent AF randomized to the lenient (n = 230) or strict (n = 207) rate control for whom QOL data was available. Rate control was achieved with β-blockers, nondihydropyridine calcium-channel blockers, and digoxin, alone or in combination, until the target heart rate was achieved. Medication usage was recorded at the end of the dose-adjustment period. The minimum follow-up was 2 years (median, 3 years). QOL was measured with the Medical Outcomes Study 36-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36), the University of Toronto AF Severity Scale (AF severity scale), and the Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory-20 (MFI-20) questionnaires, administered at baseline, 12 months, and at the end of the study.

The baseline characteristics were similar in the 2 groups: mean age of 68 years, 66% male, mean duration of AF of 18 (6-58) months, and a resting heartbeat of 95±12 per minute. Hypertension was present in 60%, coronary artery disease in 19%, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in 13%, and diabetes in 9%, while 8.5% had a prior heart failure hospitalization. The mean ejection fraction was 53%. Fifty-eight percent of the patients had symptoms, most commonly dyspnea (37%), fatigue (31%) and palpitations (24%); 42% of the patients were asymptomatic. The rate control drugs used were β-blocker alone (33%), β-blocker with verapamil/diltiazem or digoxin (28%), verapamil/diltiazem with digoxin (8.5%), sotalol or amiodarone (3.4%), no drug (6%), and other combinations in the remainder.

While both groups had a mean baseline heart rate of 95+12 beats/min at baseline, 79% of the strict control group achieved a heart rate <80 beats/min at the end of the dose-adjustment period, compared with 2% of the lenient control group. However, it should be noted that the resting heart rate averaged 85 beats/ min in the lenient control group and 75 beats/min in the strict control group at 1 year, 2 years, and at the end of the study. There were almost 9 times more patient clinic visits in the strict control group (684) than in the lenient control group (75), yet only 67% of the strict control group achieved the target heart rates.3

At 12 months of follow-up and at the end of the study, there were no differences in any of the SF-36 subscales between the lenient and strict control groups. Additionally, there was no relationship with heart rates at baseline, at end-of-dose adjustment period, or at the end of the study. There were also no differences in the AF severity scale or the MFI-20 scale from baseline to 12 months of follow-up to end of the study. Heart rate reduction was not related to improvements or worsening of QOL in any of the study measurements.

Worsening of the SF-36 subscales were associated with symptoms at the end of study, older age, diabetes, lower left ventricular ejection fraction, thicker septum, hospitalization for heart failure, β-blocker use, an arrhythmic event during the study, major bleeding, and female sex. Symptoms at the end of the study were also associated with worsening in the AF severity scale and worsening on the MFI-20 scale. In summary, changes in QOL were related to age, symptoms at baseline and at the end of the study, severity of underlying disease, and female sex.

References

1. Wyse DG, Waldo AL, DiMarco JP, et al. A comparison of rate control and rhythm control in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2002; 347:1825-1833.

2. Roy D, Talajic M, Nattel S, et al. Rhythm control versus rate control for atrial fibrillation and heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2667-2677.

3. Van Gelder IC, Groenveld HF, Crijns HJ, et al. Lenient versus strict rate control in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1363-1373.

4. Wann LS, Curtis AB, Ellenbogen KA, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA/HRS focused update on the management of patients with atrial fibrillation (update on dabigatran): a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines. Circulation. 2011;123:1144-1150.

5. Camm AJ, Kirchhof P, Lip GY, et al. Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation: the Task Force for the Management of Atrial Fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2010;31:2369- 2429.

6. Smit MD, Crijns HJ, Tijssen JG, et al. Effect of lenient versus strict rate control on cardiac remodeling in patients with atrial fibrillation data of the RACE II (Rate Control Efficacy in Permanent Atrial Fibrillation II) study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:942-949.

7. Groenveld HF, Crijns HJ, Van den Berg MP, et al. The effect of rate control on quality of life in patients with permanent atrial fibrillation data from the RACE II (RAte Control Efficacy in permanent atrial fibrillation II) study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:1795-1803.

8. Jenkins LS, Brodsky M, Schron E, et al. Quality of life in atrial fibrillation: the Atrial Fibrillation Follow-up Investigation of Rhythm Management (AFFIRM) study. Am Heart J. 2005;149:112-120.

9. Singh BN, Singh SN, Reda DJ, et al. Amiodarone versus sotalol for atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1861-1872.

10. Cooper HA, Bloomfield DA, Bush DE, et al. Relation between achieved heart rate and outcomes in patients with atrial fibrillation (from the Atrial Fibrillation Follow-up Investigation of Rhythm Management [AFFIRM] study). Am J Cardiol. 2004;93:1247-1253.

COMMENTARY

Lenient vs Strict Rate Control and QOL

In both the AFFIRM1,8 and AF-CHF2 trials, there was no statistically significant difference in QOL for rate control compared with rhythm control, although the Sotalol Amiodarone Atrial Fibrillation Efficacy (SAFET) trial9 did find that sinus rhythm was associated with improved QOL, irrespective of treatment assignment. Additional analysis of the AFFIRM data showed no correlation between resting heart rate or heart rate with moderate exercise and QOL.10 In the RACE II trial patient cohort there was no difference in overall QOL measurements between the strict and lenient rate control groups; symptoms, age, sex, and underlying heart disease, but not the amount of rate control, influenced QOL. This study did find that presence of symptoms was related to QOL and changes in QOL over time, but the type of rate control did not affect how symptoms changed over time.

First, it should be noted that 42% of the patients did not have any symptoms. This may indicate a selection bias in patients assigned to rate control in the first place, but will limit the impact of the different rate control strategies on QOL outcomes. Interestingly, the most common symptoms were dyspnea and fatigue rather than palpitations, suggesting the underlying heart disease rather than the rate may be the critical factor in defining symptoms. Additionally, patients with permanent AF are known to have fewer symptoms compared with patients with paroxysmal AF, in whom palpitations are the most common symptom. Second, it is possible that side effects such as fatigue seen with higher doses of β-blockers used in the strict rate control group may have offset any potential QOL benefit from the lower rate. Third, the ultimate difference of only 10 beats/min on average between the 2 groups may not have been large enough to have an effect on QOL measurements. Finally, it should also be noted that RACE II was a non-inferiority study and was not powered to detect differences in the primary clinical end point noted above; hence, it may not have the power to detect QOL differences.

If a strict rate control strategy is chosen, a Holter monitor should be considered to assess for pauses and bradycardia, while an exercise test may be useful to assess heart rate with exercise. If the lenient rate control strategy is chosen, then left ventricular function should be monitored, as this will raise concerns of possible tachycardiamediated cardiomyopathy developing over the long term. However, despite the finding in the remodeling sub-study of RACE II also recently reported,6 there are no longterm data on the effects of the more lenient strategy on ventricular function; hence, the possibility of tachycardia- mediated cardiomyopathy remains a concern in the long term. Lenient rate control would be expected to be more convenient for many patients, requiring fewer office visits and testing. The choice of rate control drugs will depend on underlying conditions such as heart failure or COPD, age, and the heart rate target.

The results of this trial will apply to patients with permanent AF who are relatively asymptomatic, but not those with newly diagnosed or paroxysmal AF who are highly symptomatic, where rhythm control is the option likely to be desired by the patient. Thus neither the present data nor other studies in the literature support the conventional and arbitrary definition of strict rate control in AF.

It is still possible that for highly symptomatic patients, strict rate control may have a beneficial effect on QOL. While the choice of rate control versus rhythm control is one that should be individualized, this is also true for the choice of lenient versus strict rate control.

About the Author

Noel G. Boyle, MD, PhD, is professor of medicine, director of the Cardiac EP Fellowship Program, and co-director of the Cardiac Arrhythmia Center at the Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center in Los Angeles, California. He earned his medical degree and PhD at Trinity College Dublin School of Medicine, Dublin, Ireland, and completed an internship in St James’s Hospital, Dublin, and residency in Internal Medicine at the Medical College of Wisconsin. His fellowships in cardiology and cardiac electrophysiology were at Beth Israel Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA. His research interests include mechanisms and management of atrial fibrillation, atrial fibrillation in heart failure, and management of ventricular tachycardia. He is a Fellow of the American College of Cardiology, the European Society of Cardiology, the Heart Rhythm Society, and the Royal College of Physicians of Ireland. Noel G. Boyle, MD, PhD The authors studied a total of 437 patients with permanent AF randomized to the lenient (n = 230) or strict (n = 207) rate control for whom QOL data was available. review